The release of a new AI model by the Chinese startup DeepSeek in January 2025, known as R1, captured global attention. The company claimed to have developed a model that performs on par with those of leading American tech firms such as OpenAI, xAI or Anthropic, but at significantly lower cost and requiring far less computing power. This announcement sent shockwaves across the globe, signalling a potential reshaping of the global AI race between the US and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

China’s restricted access to cutting-edge chips due to American export controls had led many to doubt its ability to develop a frontier AI model. The release of DeepSeek’s model has challenged those assumptions, calling into question the effectiveness of the US’s ‘small yard, high fence’ strategy. Crucially, the Chinese firm’s breakthrough relies primarily on the model’s algorithmic efficiency, dealing a serious blow to the technical and business model long championed by US tech giants.

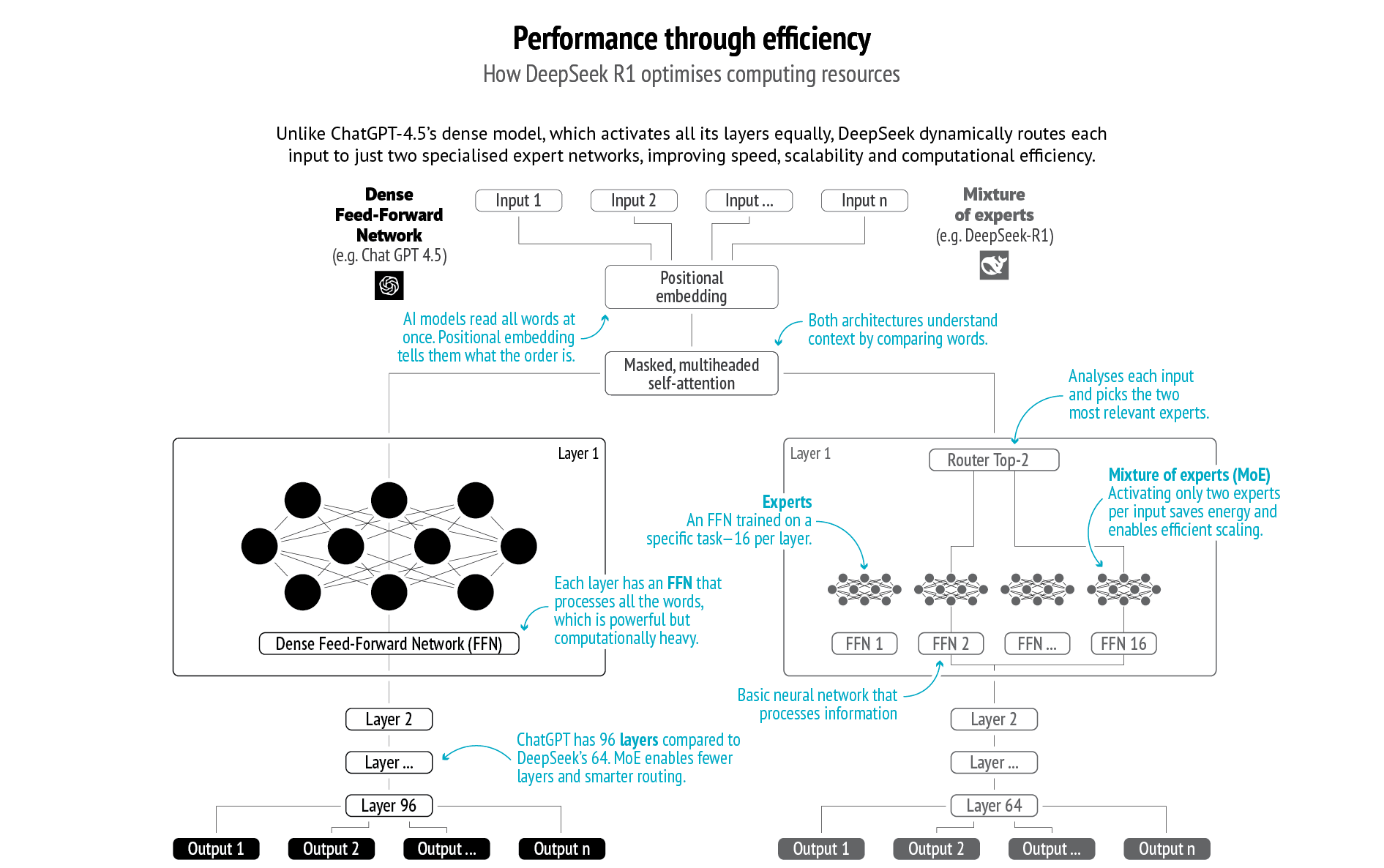

In reaction to US export controls, DeepSeek compensated for the computing power shortcomings it faced by improving its model’s efficiency. In particular, it focused on inference enhancement, generating text faster, at lower cost, and with higher quality, once the model is trained. Techniques such as mixture-of-experts (MoE), selective activation, and transfer learning allow for the optimisation of computational resources(1). In particular, the MoE architecture activates only a few relevant subnetworks of the model during the inference, which significantly reduces computational overhead.

Even so, Chinese AI development is not fully autonomous. DeepSeek’s techniques build on foundational research developed by other firms, notably Meta’s LLaMA series. DeepSeek has also acknowledged using US-manufactured Nvidia chips instead of Chinese semiconductors. Without access to US research and hardware, DeepSeek would thus have not achieved what it did. In addition, despite notable progress by Chinese chipmakers, competing with the technological sophistication of American AI chipsets, especially for compute-intensive pre-training, will remain a significant challenge in the coming years.

Data: Zhang, S. et al., ‘A survey on mixture of experts in large language models’, 2024; DeepSeek, ‘DeepSeek-VL: Scaling Vision-Language Models with Mixture of Experts’, 2024; Daily Dose of DS, ‘Transformer vs. Mixture of Experts in LLMs’, 2025

Room for alternative models

R1 is not a fully open-source model as DeepSeek did not release its complete training data or codebase; but it is an open-weight model, meaning its trained parameters – the weights – are publicly available, allowing others to use, fine-tune and deploy the model. It thus makes AI accessible and usable to a broader range of actors with limited technical expertise or computing resources. DeepSeek R1 is also released under the MIT License, making it freely available for commercial use. This lowers the barrier to entry for actors lacking capital or infrastructure and facilitates the development of AI applications across sectors like finance, manufacturing or healthcare. Additionally, by focusing on algorithmic innovation and cost reduction, DeepSeek establishes efficiency as a new key parameter for future frontier AI innovation. As computing power is becoming a critical asset, resource optimisation could be a decisive factor in the AI race.

DeepSeek thus embodies a shift from the prevailing business and technical model based on closed-source, proprietary and scale-first AI development towards more flexible and resource-conscious approaches. It not only challenges the widespread ‘winner-takes-all’ assumption in the digital sector, but also raises the question of whether smaller-scale companies, including European ones, could make significant progress with ‘good enough’ AI models. Such models, while not necessarily state-of-the-art, can perform specific tasks effectively within a given context, prioritising practical utility, affordability and accessibility. They are particularly useful for edge models (especially the Internet of Things), chatbots, transcriptions or machinery monitoring.

Amplifying risks

The release of R1 has also raised several security-related concerns. The first issue is data security and privacy. DeepSeek’s terms of service indicate that user data may be stored in China and used for training purposes, raising serious questions about compliance with international data protection standards, including the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC), South Korea’s national data protection authority, has reported that personal information from over a million South Koreans was transferred to China without consent(2). Suspicions about potential backdoors enabling government access have deepened mistrust, especially given China’s recently amended Intelligence Law, as it includes a blanket requirement for Chinese entities and individuals to cooperate with Chinese security services(3). This has led countries such as Australia, India, Italy and Taiwan to ban DeepSeek from government devices. Nonetheless, such concerns are neither new nor unique to China. The DeepSeek controversy has reignited broader debates about data surveillance and the role of intelligence agencies, particularly given the close ties between the US government and major American tech firms.

DeepSeek has also faced criticism for adhering to Beijing’s content regulations on politically sensitive issues such as the Tiananmen Massacre, Taiwan and the repression against Uyghurs, leading to accusations of restricting data access and embedding ideological bias. While censorship only applies to the online version, the model is likely to reflect the authoritarian context in which it was developed, as any AI model is shaped by its training data and the political values it embeds. DeepSeek has also fallen short in protecting sensitive user data, including chat histories and authentication keys(4), raising concerns about both free speech and cybersecurity.

Beyond these immediate normative and security issues, DeepSeek’s ambition to develop AI models approaching or exceeding human cognitive abilities, known as artificial general intelligence (AGI), is the most concerning. Advancements in this field would not only exacerbate tensions in the US-China AI race leading to the development of unsafe models, but could even lead to the development of AI systems escaping human control. Robust multilateral frameworks for AI governance are urgently needed.