MICAELA BURROW

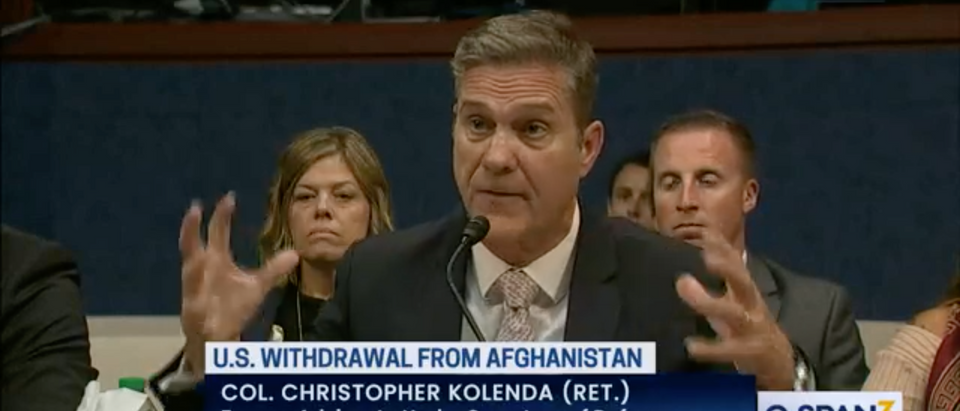

A retired Army colonel said Thursday that the lack of a leader directing the military and State Department actions on the ground during the Afghanistan withdrawal created confusion and contributed to the perceived failures that marked the war’s end in 2021.

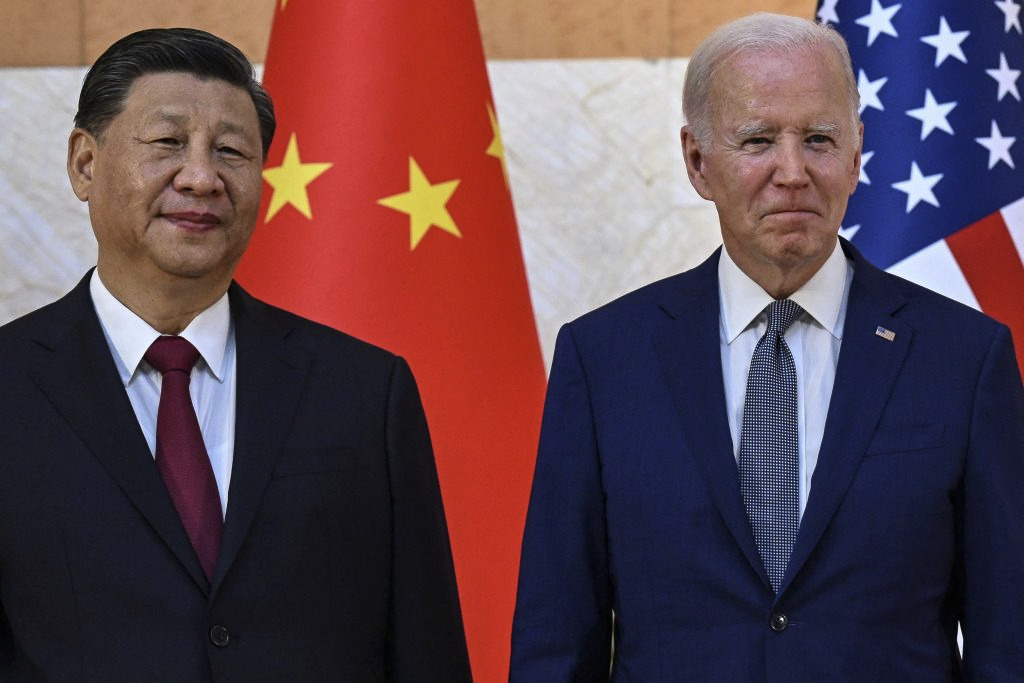

Republican Rep. Michael McCaul of Texas, at a Foreign Affairs subcommittee hearing on the Afghanistan withdrawal, said the Biden administration had yet answer his request for evidence of an evacuation plan, suggesting that perhaps none existed in the first place. The Biden administration said it accounted for all possible contingencies, but the high-ranking colonels who commanded in Afghanistan testified to Congress that the administration chose an inferior course of action that failed to account for the Taliban’s catapult toward Kabul.

“There’s nobody functionally in charge of our wars on the ground” Retired Col. Christopher Kolenda, a combat leader in Afghanistan who participated in the Doha negotiations with the Taliban, told the panel. (RELATED: Pentagon Did Not Force Family Of Fallen Marine To Foot The Bill For Flight To Arlington Cemetery)

While the President and National Security council made decisions from Washington, the military, State Department and other U.S. organizations worked on the ground without anyone directly negotiating between them, Kolenda said. These “bureaucratic silos” created problems during the evacuation.

“I have not seen an evacuation plan,” McCaul said. “Nobody knows who’s really in charge because there was no plan in place.”

U.S. Central Command provided a selection of plans to senior commanders, and Generals Mark Milley, Austin Miller and Kenneth McKenzie recommended not to withdraw until conditions were met, Retired Col. Seth Krummich said. However, civilian leaders in Washington rejected evacuation recommendations given by the generals in charge of the military dimension of the withdrawal.