Ofer Shelah

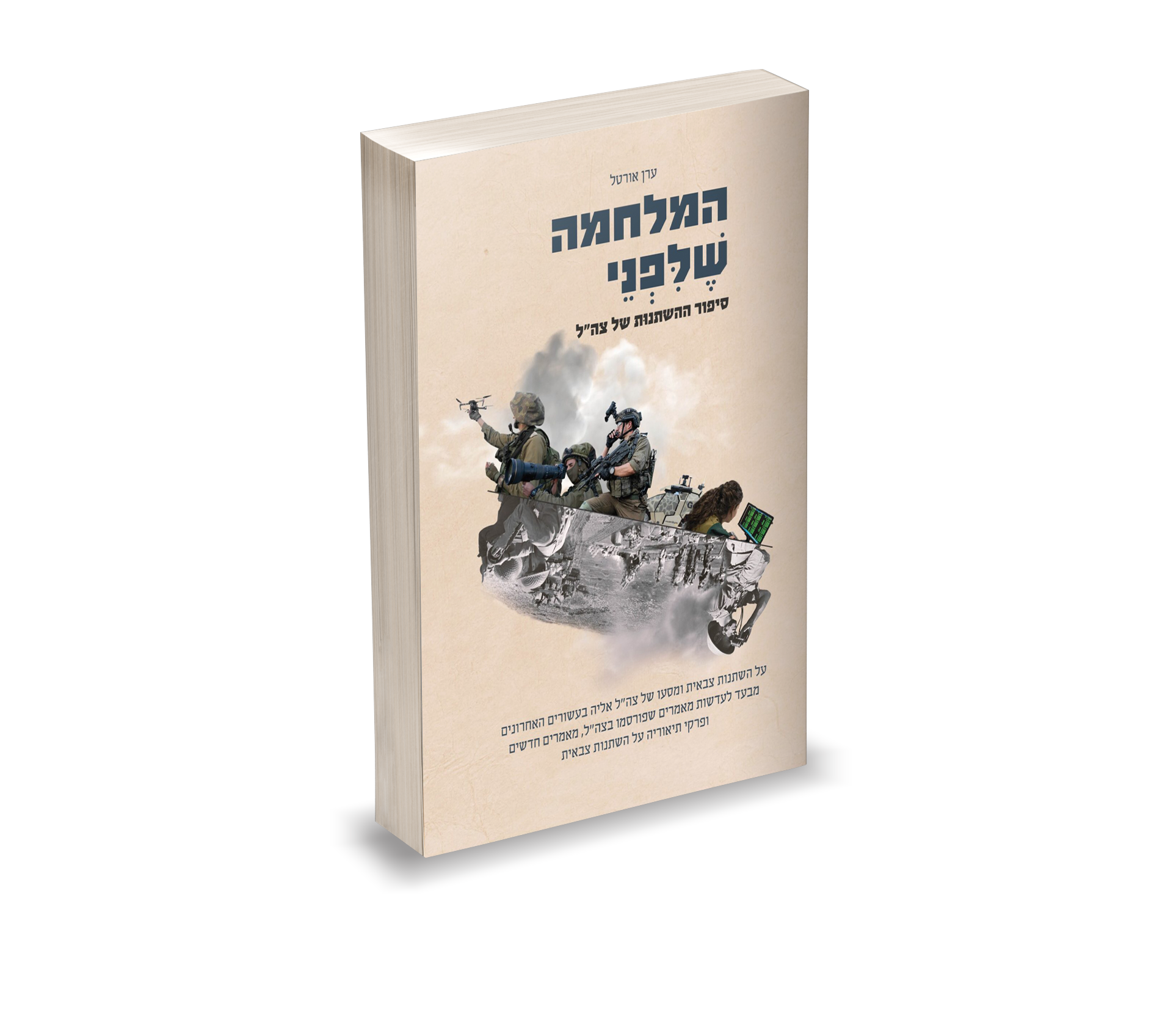

The Battle before the War: The Inside Story of the IDF’s Transformation by Brig. Gen. Eran Ortal gives the reader a slightly awkward feeling, and on second reading—even more so. This feeling is intensified by the fact that the author has, since 2019, been the commander of the Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies. Ortal is therefore a senior contemporary practitioner within the IDF, who is offering us, as Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Aviv Kochavi says in his introduction to the book, “a glimpse into the intellectual machinery of the IDF in recent years” (p. 8).

The awkwardness is furthered by Kochavi’s introduction, where he writes that the book’s “greatest importance in my eyes is the systematic, developed discussion of the manner in which militaries in general and the IDF in particular can and should continue to examine themselves, develop and change…The book expresses the spirit of self-criticism and in-depth study that are expected from the senior command” (p. 8). This is an unfortunate description, given that the book does not even live up to its subtitle, let alone to the Chief of Staff’s praise. It is not a “story” because it doesn’t have an actual beginning or end, and it is hard to learn from the book whether the IDF has indeed changed, and if so how. The book is not systematic or developed, and is far more self-congratulatory than self-critical. In that sense it does reflect a certain sprit that is present in the IDF today—and that is what is most disturbing.

The self-adulation begins on the book’s first page, implying that the work was written by a man who dared to rebel against conventions and almost risked his life to do so. Ortal thanks “the commanders who identified my ability to contribute to the IDF,” those who “chose me for demanding operational roles and pushed me to fulfill more than what is typical,” and finally, “partners along the way who believed in change and went against the current with me for years” (p. 6). This same sense of grandiosity is applied to the book itself, including praise by the author for his own work (e.g., “the article presents the principles of the critical-systemic learning process in a clear, succinct manner”—and this is a relatively modest example.)

The Battle before the War is a collection of articles published by Ortal over the past decade, either alone or in collaboration with others. That is not necessarily a bad format, and a collection of articles can be a book and even tell a story—if it has a logical order, developed themes, and a common thread that runs throughout the articles and leads to a message or descriptive picture. Instead, here is a collection of articles presented in seeming free association, with many only casually related to the “story of change in the IDF.” This is the case in articles such as “The War in the Atlantic 1940-1945 and Our Situation Today,” or “Military Innovation and the Lack Thereof during the Great Depression,” neither of which has relevant insights for Israel. A theoretical article such as “Genealogy as a Tool for Self-Examination,” which, at best, could have served as part of the introduction, appears midway through the book, and at the end there is an article on “Competitive Strategy vis-à-vis Iran”—certainly an important subject, but almost totally devoid of any reference to the theme of change in the IDF.

The IDF has in fact faced substantial paradigmatic and practical confusion over recent decades, regarding the role and significance of its primary force—the ground force.

The articles that do relate to IDF activity over the past few decades tend to repeat themselves, offering details without drawing any practical or new conclusions, and mainly laud technological advances and hint at the revolutionary possibilities they entail, without explaining what the IDF is or is not doing to realize such possibilities. It is difficult to see them as the story of the development of change in the military or to find insights about the direction that the new change—which has not yet occurred—will lend the military.

Over the past decades several books and articles, including those by active duty senior officers, have discussed the IDF in a critical manner. In contrast, the minimal criticism in Ortal’s writing is worded in a way that should not be called “the spirit of self-criticism”—certainly not in relation to the IDF of today. Even when there is a statement that gently calls into question current rhetoric—such as explaining that the claim that the “campaign between the wars,” which senior officers often present as a dramatic innovation in the history of warfare, is actually a continuation of the routine security paradigm of the 1950s—it is wrapped in a thick layer of self-admiration: “The campaign between the wars is no less than a new, original form, brimming with vitality, of the element of security doctrine known as routine security” (p. 163). I don’t know what the role of an expression such as “brimming with vitality” is in a military-professional book; Ortal does not explain what is original in the campaign between the wars, and “routine security” is a practice carried out on a daily basis, not an element of security doctrine.

The IDF has in fact faced substantial paradigmatic and practical confusion over recent decades, regarding the role and significance of its primary force—the ground force. The expression “the maneuver dilemma” is forbidden for use within the IDF today (as Ortal notes in the book), but this rhetorical trick does not solve the problem at hand.

This confusion is fundamentally related to the definition of the desired achievement in battle. In the past this achievement was clear: defeating the enemy by conquering its territory and destroying its power such that it is unable to fight effectively. Today Israel does not define—and military commanders do not propose—any achievement in battle other than achieving quiet, which leaves the ability to achieve this outcome entirely in the enemy’s hands, given that it decides when there will or will not be quiet.

This confusion has many root causes, including changes in the enemy; change in the nature of war in the Middle East and around the world; and changes in society, politics, and decision making processes in Israel. They undermine the familiar foundations of the unofficial security doctrine: deterrence, warning, and decision, all of which are questionable today. The result in practice is that in each of the last wars there was hesitation about whether to use ground forces, and when they were actually used (during the Second Lebanon War and Operation Protective Edge) this occurred late, the aims were unclear; the plan chosen was one troops were not prepared for; and the accomplishments were minimal and tenuous, and thus further intensified hesitations about the future use of ground troops.

This is also a subject of numerous books and articles, inside and outside the IDF. The most interesting sections of Ortal’s book are actually those that show just how late the army is in recognizing what is already clear in its surroundings. For example, the author quotes the introduction to the booklet “Ground Forces on the Horizon,” which was written based on diligent work by military headquarters regarding the future of the ground forces; in the excerpt Maj. Gen. Aharon Haliva writes that “the ‘Ground Forces on the Horizon’ process was the first time that the ground forces identified, in an official, clear manner, that there is a fundamental crisis of ground maneuvers” (p. 165). This was written in 2015, almost a decade after the Second Lebanon War. Maj. Gen. (res.) Guy Tzur, whose last role in the IDF was as commander of the ground forces, is quoted in the book as saying “From ‘Protective Edge’ I came out with a euphoric feeling based on the sense that it was proven that confrontation can happen without maneuvering. I came back down to earth more quickly than I expected” (p. 14).

From personal acquaintance, I know that Tzur, like Haliva, is an honest, thoughtful officer. But everyone who remembers the events of the summer of 2014—a 51-day battle with 75 killed, against a terror organization that is inferior to the IDF in every way, during which Israel agreed time after time to ceasefires and Hamas refused, and ultimately only achieved temporary quiet—must certainly be wondering how an IDF major general could come out euphoric, based on the success of “confrontation without maneuvering.”

An organization such as the military that works constantly and has a closed mentality that distances it and its commanders from what is going on around them, has limited ability to learn and change of its own accord. The problem is that instead of dealing with this structural difficulty, the army has preferred in recent years to sing its own praises, internally and externally, for so-called innovations and for achievements that are indisputably modest. An outstanding example was the bombing of the Hamas “metro” during Operation Guardian of the Walls—an action carried out without the central component of the plan, which included substantial offensive ground maneuvers, achieved almost nothing by any parameter, and was publicized in an embarrassing manner.

There is another factor making real change difficult in the army: most of the discussion on these subjects takes places within the IDF, as in the case of Ortal’s book. Unlike in other countries, Israel has no significant component of academic research on the military, other than on certain aspects of its relations with Israeli society. The government officials tasked with overseeing the military do not deal with this at all, and the Ministry of Defense relies almost exclusively on the IDF for all matters of knowledge, planning, and examination of alternatives. For its part, the public doesn’t really want to know. It consistently prioritizes security in public opinion surveys but leaves the discussion about how security is achieved in practice—which for the most part is not classified, and rightfully so—to “the higher-ups who are in the know.”

Unlike in other countries, Israel has no significant component of academic research on the military, other than on certain aspects of its relations with Israeli society.

The discourse about the IDF that does happen takes place in limited journalistic contexts that relate to one story or another, or in alarmist tones (for example, the discussion of criticism by Maj. Gen. (res.) Yitzhak Brick, formerly the IDF ombudsman). Those who take part in it are former senior officers who are still linked by an umbilical cord to the army and maintain their place at the table by blatantly engaging in PR, especially during emergency situations.

Another factor obscuring this discussion is that Israel is a superpower of technological innovation and rapid embedding of new technologies in combat systems. Iron Dome is an example, not only of the speed in which a seemingly unsolvable problem could be solved, but also of speedy, efficient incorporation of this technology, thanks to tight links between the technological and combat systems and ability to “cut corners” in the positive sense.

However, there are problems that technology cannot solve, and when one encounters such a problem it is particularly egregious to assume that we solved it because we have new technology. From 2006 until today, the technology the IDF uses has improved dramatically. However, many of the core problems have not changed and will not be solved without a clear-eyed discussion that is free of self-congratulation and defensiveness and involves high-ranked civilian and military figures and the public.

Unfortunately, Brig. Gen. Ortal’s book does not advance such a discussion.

No comments:

Post a Comment