Walter Landgraf & Nareg Seferian

Executive Summary

This report has two objectives: first, to present an account of the conflict with an emphasis on analytically useful categories and context up to the present, and second, to discuss local, regional, and global consequences of the latest developments of the dispute, including policy implications and recommendations.

An Account of the Conflict

- Azerbaijan’s lightning attack on Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023 ended three decades of de facto independence for the breakaway region. Previously, the Armenian-populated Nagorno-Karabakh Republic had shown remarkable durability, enabled by support from Armenia and Russia, the latter more after the Second Karabakh War of 2020. However, changed regional and global power dynamics since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 encouraged an opportunistic Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, to deliver the death knell to Nagorno-Karabakh.

- Prior to Azerbaijan’s latest assault, two wars had been fought over Nagorno-Karabakh. The first began as a limited conflict, which turned into a larger-scale war when the USSR dissolved. Its ceasefire in 1994 resulted in the establishment of the de facto independent Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. The second war, in 2020, resulted in Azerbaijan reversing the gains of the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians and further isolating the territory. Russia mediated the ceasefire and thereafter stationed peacekeepers in the region.

- Many issues are still unresolved in this long-running conflict. The biggest concern is directing much-needed humanitarian aid to those displaced by the latest violence. There also remains potential for future Azerbaijani incursions into Armenia to secure a path to its exclave of Nakhchivan.

Consequences of the Dispute’s Latest Developments and Implications

- Nagorno-Karabakh has important implications for other international conflicts grappling with the competing principles of territorial integrity and national self-determination. The principle of nonuse of force is also affected by the fall-out of this dispute, risking the normalization of international violence with impunity.

- The US has limited foreign policy options to affect the current situation on the ground. One approach is to expand the American diplomatic footprint in the region to reinforce its influence. More consequentially, it should work with the European Union and regional players to implement an enduring monitoring mechanism to prevent renewed escalation. This effort should focus on reducing human suffering while improving the quality of life of people displaced by violence, and be pursued with a presence on the ground in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh to facilitate the potential return of refugees to their homes.

Azerbaijani service members guard the area, which came under the control of Azerbaijan’s troops following a military conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh against ethnic Armenian forces and a further signing of a ceasefire deal, on the border with Iran in Jabrayil District, December 7, 2020. Picture taken December 7, 2020.

Introduction

On September 19, 2023, Azerbaijani forces initiated a massive attack on Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian-populated and effectively self-governing region inside internationally recognized Azerbaijani territory.[1] Russian peacekeepers, stationed in the area since 2020, did not step in to stem the fighting but intervened to arrange for a cease-fire. Within 24 hours, the Nagorno-Karabakh leadership gave in, and, for the first time, Baku could claim full control over the contested territory. This ended 30 years of de facto independence for the tiny statelet. The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic[2] —never recognized by any sovereign state including Armenia—was initially declared by its president as formally ceasing to exist on January 1, 2024.[3] That decree was later annulled by the government in exile.[4]

Despite being portrayed in the West as a “frozen conflict,” there had long been a risk of renewed violence in Nagorno-Karabakh. Peace negotiations over several years made no substantial progress, arguably because of a lack of interest from major power centers and because the status quo had displayed enduring stability. At the same time, the military build-up in Azerbaijan and occasional minor—and a few major—flare-ups suggested further rounds of fighting, culminating in the Second Karabakh War of 2020. Since the autumn of 2020, the situation in and around Nagorno-Karabakh, also referred to as Artsakh by Armenians, has been kinetic and fast-moving, regularly drawing in the active mediation of external actors, including the US The fighting in September and the subsequent mass exodus of the 100,000-strong Armenian population from Nagorno-Karabakh may end up being only the latest chapter in further violence and displacement to come.

This report has two objectives: first, to present an account of the conflict with an emphasis on analytically useful categories and context up to the present, and second, to discuss local, regional, and global consequences of the latest developments of the dispute, including policy implications and recommendations.

Competing Discourses and Narratives

The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh has many interconnected and overlapping components. Arguably the most consequential of them are the Armenian and Azerbaijani discourses about the issue, often framed in nationalist terms. At the heart of the matter is the question of territory and demographics—put another way, the relationship between space and ethno-national or cultural identity.

The dispute hinges on the identity of the space and how Armenians and Azerbaijanis perceive the identity of the other. Armenian and Azerbaijani discourses typically mirror one another in this regard. Common categories of victimhood caused by the other and irredentist claims on one another’s territory are readily identifiable as Stephan Astourian observes.[5] When it comes to perceptions of identity, he argues that categories of modern Armenian and Azerbaijani national identity arose together in the early 20th century—the Azerbaijani national identity in opposition to the Armenian identity, and the Armenian more in contrast with the Turkish identity. Altay Göyüşov takes a broader view of the development of Azerbaijani nationalist identity in the context of other waves of thinking at the turn of the 20th century.[6] Razmik Panossian likewise characterizes the development of the modern Armenian national identity in a “multilocal” manner across Romanov/Soviet, Ottoman, and diasporan spaces.[7]

Common, if laterally inverted, framings among Armenians and Azerbaijanis about the other are not surprising because political thinking, social and cultural norms, and expectations of behavior among the elites in both Armenia and Azerbaijan ultimately have shared origins in the political culture of the Romanov Empire, later the USSR. Most consequentially, Stalin’s very conceptualization of national identity had far-reaching implications for all the peoples of the USSR.[8] Besides language, culture, economic ties, and “psychological make-up,” Stalin expected nations to have an identifiable history and territory. Perceptions on both of those topics tend to undergo subjective developments—nowhere more so than during the seven decades of the Soviet Union.

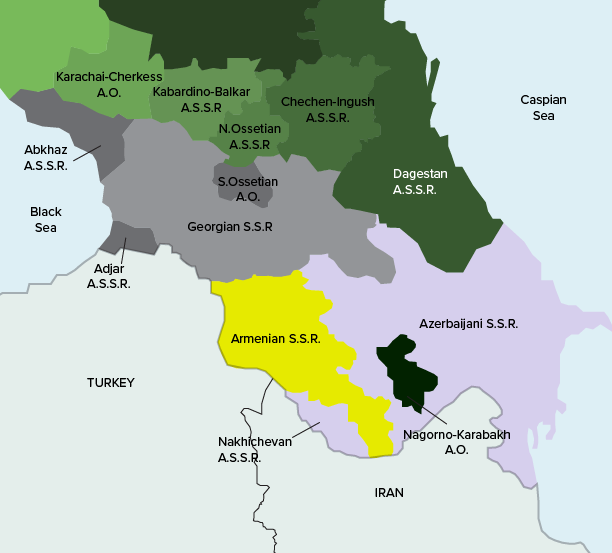

Drawing Territorial Borders, Writing History, and Crystallizing National Identity in the USSR

While the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh has a long history, the key legacy is from the collapse of the Soviet Union and, with it, the institution of Soviet ethnofederalism, which constructed ethnic cleavages. The territoriality of the Soviet Union had an effect on the development of local, regional, and union-wide identity, with accompanying power dynamics. There were 15 union republics that constituted the USSR at the topmost level. Criteria for that status included population thresholds and external borders. In principle, the union republics had the right to secede, and, indeed, all became independent countries in 1991. There were also many other administrative divisions with various levels of autonomy. The territorial administration of the Soviet Union—various units, their names, and their borders—saw several changes ranging from the elimination in 1956 of the 16th union republic, the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic, to the transformation of the Kirghiz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic within Soviet Russia first to the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic in 1925, then to the union-level Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic in 1936.

Even though power was indeed concentrated at the center in Moscow, each level had opportunities to influence different spheres, such as education, including the production and propagation of history and, by extension, national identity. As Rogers Brubaker, Francine Hirsch, and other scholars have put forward, something of an irony thus came to be developed in the USSR. Instead of the Soviet man arising from that ostensibly communist, internationalist, revolutionary, cosmopolitan society, national identities became crystallized in a way that they never were in the times of the Czar.[9]

They were also territorialized. Ethno-national identities developed strong associations with the borders drawn around them. The administrative units of the USSR may not have been sovereign states, but they became recognizably national territories.

Relationships between national identity and territory were particularly complex in the contrast between a given unit’s “titular nationality” —the name of the nation in the title, such as the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic or the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic—and other nationalities forming part of the population of the unit or the higher level to which it was subordinate. These arrangements were inconsistent. Some titles included more than one nationality. The Jewish Autonomous Oblast, meanwhile (bordering China in the Far East, still a part of the Russian Federation), never achieved a majority-Jewish population.[10]

Krista Goff offers a rich account of Soviet Azerbaijan in this regard.[11] The Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) was established within it in 1923 as a national territorial entity with an ethnic Armenian majority. In fact, the Bolsheviks drew the boundaries of the new autonomous region to exclude several Azerbaijani villages to ensure an overwhelming Armenian majority. In the long run, this was an arrangement with a structural flaw as it made Nagorno-Karabakh a place of elusive allegiances—an ostensibly autonomous Armenian province within Soviet Azerbaijan, physically close to the titular Armenian republic. The NKAO was separated at its closest point by just a few miles from the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. Having the same majority or titular nationality forming part of two administrative units —one union-level, one autonomous in a second union-level republic—was an arrangement unique in the Soviet Union, again reflecting inconsistencies in the territorial administrative structure of the USSR.

Those inconsistencies did not go unnoticed in popular Armenian and Azerbaijani narratives. As another example of mirroring discourse, it is common to hear among both Armenians and Azerbaijanis that “Stalin gave away” territory from one to the other in this case. Arsène Saparov presents a nuanced perspective, arguing that the early Bolshevik leadership resorted to ad hoc decisions of the divisions of territory on the ground in the Caucasus, using autonomy as a conflict management tool in the violent period of the late 1910s and early 1920s.[12] There were disputes at that time in other areas of the South Caucasus with mixed populations as well, with different outcomes—Nakhchivan/Nakhichevan, Syunik/Zangezur, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Adjara, and Samtskhe-Javakheti/Javakhk, among other places.

In the end, the national territorial make-up of the Caucasus within the USSR consisted of somewhat incontiguous administrative units.

Soviet Caucasus

The lines may seem arbitrary, as borders can be, but the USSR was a single country. Just as the Upper Peninsula’s separation from the rest of Michigan or driving through Rhode Island to get to different parts of Massachusetts do not offer any practical hindrances, the administrative divisions of the South Caucasus had little to no consequence in everyday life. They were not perceived or experienced as hard-and-fast divisions across spaces.

1988–1994: Matters Come to a Head

Nationalist readings of history and expectations of changes to borders, however, were not too far from the surface. In Soviet times, there were a few attempts to petition Moscow for a change in status and belonging of the NKAO in the 1960s and ’70s as a means of resisting discrimination and adverse population policies, according to the prevailing Armenian narrative.[13] In Azerbaijani discourse, for its part, Nagorno-Karabakh is framed as a privileged autonomy populated by Armenians resettled in the 19th century by the Romanov regime.[14]

In the final years of the USSR, perestroika and glasnost allowed for more liberal and critical ideas to spread and mobilize segments of the population. Within the context of these reforms, the conventional understanding of what constituted normal behavior shifted and windows of opportunities to contest the existing order opened. In effect, a new political space for dissent had come into existence. Encouraged by a rising tide of nationalist mobilization elsewhere in the Soviet Union, particularly in the Baltic States and Georgia, the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh launched a new quest to secure further rights for their region, mainly by moving to join Soviet Armenia.[15]

While liberalizing reforms provided the opportunity structure for groups to mobilize and fight, there were other necessary preconditions for the outbreak of war over Nagorno-Karabakh. Stuart Kaufman argues that these involved the existence of myths justifying hostility as well as the prevalence of fears about group extinction.[16] When combined with the opportunity to act on such anxieties politically, violence and war are likely outcomes. All these conditions existed in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Nagorno-Karabakh as central authority waned in the final years of the Soviet Union.

The First Karabakh War

The violence began in 1988 as a smaller-scale interethnic, later intrastate, conflict involving a loose coalition of Karabakh Armenian militias with some support from kin in Armenia, the Armenian Diaspora, and Azerbaijani militias aided by foreign fighters from a few predominantly Muslim countries. It was characterized by a series of offensives and counteroffensives, episodes of massacre and atrocities, and the ejection of hundreds of thousands—upward of a million, by some estimates—civilian Armenians and Azerbaijanis from

their homes, with tens of thousands of casualties. It is a complicated, multilayered series of events most famously documented in the English language by Thomas de Waal and thoroughly analyzed by the International Crisis Group, among other individuals and organizations. Laurence Broers offers perhaps the richest study of the conflict to date.[17]

The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR) declared its independence as a new state separate from Azerbaijan in September 1991. By the end of that year, the war turned into a larger-scale conflict when the Soviet Union formally dissolved, and Armenia and Azerbaijan gained independence. The Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh gained the upper hand by 1994 when a Russian-mediated cease-fire agreement came into force. The result was the de facto independence of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic within de jure Azerbaijani territory. The situation on the ground was very favorable to the Armenian population, officially numbering some 140,000 people. The NKR claimed the territory of the Soviet-era NKAO as well as the neighboring Shahumyan district to its north with its majority-Armenian population but ended up with effective control extending to seven adjacent districts, in whole or in part, of Azerbaijan proper.

Nagorno-Karabakh Republic – Effective Control After 1994 Ceasefire

In the end, the first war over Nagorno-Karabakh gave birth to an unusual entity on the world map—the de facto independent state.[18] Indeed, in addition to the 15 newly recognized states, five other de facto independent, though unrecognized, “states” came into existence as a result of civil wars at the end of the Soviet era: Abkhazia, Chechnya, South Ossetia, Transnistria, and Nagorno-Karabakh. These regions each achieved internal sovereignty but lacked external recognition and thus legitimacy as states.

1994–2020: No War? No Peace

Several domestic political developments in Armenia and Azerbaijan had their effects on the period that followed, which is often referred to as “no war, no peace.” With fits and starts, the mechanism known as the Minsk Group remained in place for over 25 years under the aegis of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).[19] The latter is a body which began to take shape toward the end of the Cold War, bringing together the so-called First and Second Worlds, that is, all the states in North America and Europe, including the USSR.[20] Since the 1990s, it has served as a forum for discussing and trying to resolve various problems, particularly in the former communist space, in the Balkans, Caucasus, and Central Asia. One distinct feature of the OSCE’s post-Cold War trajectory has been the development of new institutions, enabling the requisite capabilities for conflict management and mediation, whose success has been mixed.

Although the Minsk Group has a wider membership, the US, France, and Russia took on the role of co-chairs, mediating negotiations between Yerevan and Baku, at times with the direct or indirect participation of Nagorno-Karabakh’s de facto leadership.

Two principles of international law were most frequently pitted against one another in discussions on Nagorno-Karabakh peace: territorial integrity and national self-determination. In terms of territorial integrity, there was no dispute that Nagorno-Karabakh had been a part of Soviet Azerbaijan and would thus necessarily continue being a part of independent Azerbaijan. With the end of communism, the US, among other powerful Western countries, supported the idea, enshrined in the USSR constitution, that the existing Soviet republic boundaries would be the basis for the borders of the newly independent states. The Alma-Ata Declaration of 1991 reflected that the newly independent states also supported this idea (although Armenia expressed notable reservations to that document).[21] Thus, international recognition was afforded to all top-level union republics while many other administrative units in the Soviet Union pushed for alternative outcomes, often resulting in violence. The break-up of Yugoslavia displayed similar patterns in the same period.

The Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh, meanwhile, invoked national self-determination as the point of departure, pursuing avenues ranging from conducting referenda, citing Soviet and international law, and ultimately fighting to achieve self-rule. Though not always a smooth relationship,[22] the leadership of the Republic of Armenia supported the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh. The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic became in large part effectively an extension of Armenia.

The status issue continued to dog the negotiations. On at least seven occasions, the sides came close to a whole or partial deal, usually involving some sort of compromise arrangement on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh.[23] There was never a final agreement, however, no compromise toward an enduring peace acceptable to the leaders and populations of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Nagorno-Karabakh.

In the meantime, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic entrenched its presence over the territories of the former NKAO and the surrounding areas it controlled. By the mid-2000s, the discourse and vision of Nagorno-Karabakh had expanded and morphed into the term Artsakh, which is an ancient Armenian toponym. The Kingdom of Greater Armenia, which fell in the fifth century AD, consisted of feudal provinces, one of which was in areas which overlapped to a greater or lesser extent with the NKR’s effective borders. Nagorno-Karabakh became referred to more frequently as Artsakh and was often displayed in cartography as part of Armenia as a whole.[24] There was a mirrored reaction likewise in Azerbaijani visual representations in the same period.[25]

Nagorno-Karabakh Republic or Artsakh

Especially in the 2010s, the first half of the “no war, no peace” characterization became eroded. Shootings across the border and other disturbances were frequently recorded, ending with many military and civilian casualties.[26] The most serious escalation took place across four days in April, 2016.[27] Another round of clashes unusually happened in July, 2020 farther north, across the internationally recognized borders of Armenia and Azerbaijan.[28] It ended up serving as the precursor to the Second Karabakh War.

The Second Karabakh War

The Second Karabakh War was a relatively short and limited conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, lasting from September 27 to the night of November 9–10, 2020. It is also referred to as the Forty-Four Day War, the Patriotic War (in Azerbaijan), and the Second Artsakh War (in Armenia). Up to that time, it had been the largest outbreak of fighting in the region, resulting in some 7,000 deaths of soldiers on both sides, and tens of thousands of wounded and displaced. Reports of war crimes and other human rights violations accompanied and followed seven weeks of fighting actively documented on social media.[29] If the Vietnam War was the first to enter living rooms via television, the Second Karabakh War was ever-present on smartphones in the pockets of those suffering under bombardments as well as those following global news media and online platforms.

International observers have cited the war as an occasion when drone warfare and loitering munitions played an outsized role in the outcome of the conflict.[30] Both the Armenian and Azerbaijani sides employed unmanned aerial systems (UAS) throughout the war. Nagorno-Karabakh’s arsenal mostly consisted of domestically produced reconnaissance drones while Azerbaijan fielded an extensive array of systems. The Turkish Bayraktar TB2 armed drone and the Israeli-made Harop loitering munition stood out as most effective against Armenian targets.[31] These weapons provided Azerbaijani forces with significant advantages in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) as well as long-range strike capabilities. Azerbaijan quickly achieved air superiority, exploiting obsolete Soviet-era air defenses and poor battlefield tactics deployed by Nagorno-Karabakh such as insufficient concealment and concentration of forces, turning the fight into a rout.[32]

Despite a mixed, though generally good working relationship at the time, Turkey and Russia found themselves on opposing sides of the conflict. While Turkey provided direct military support to Azerbaijan, Armenia was officially allied with Moscow through the Russian-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). This involved a mutual defense pact, akin to NATO’s Article 5. However, Nagorno-Karabakh is located inside de jure Azerbaijani territory and thus not subject to the CSTO’s mandate. This detail had long served as a sensitive point in the close security relationship between Armenia and Russia.

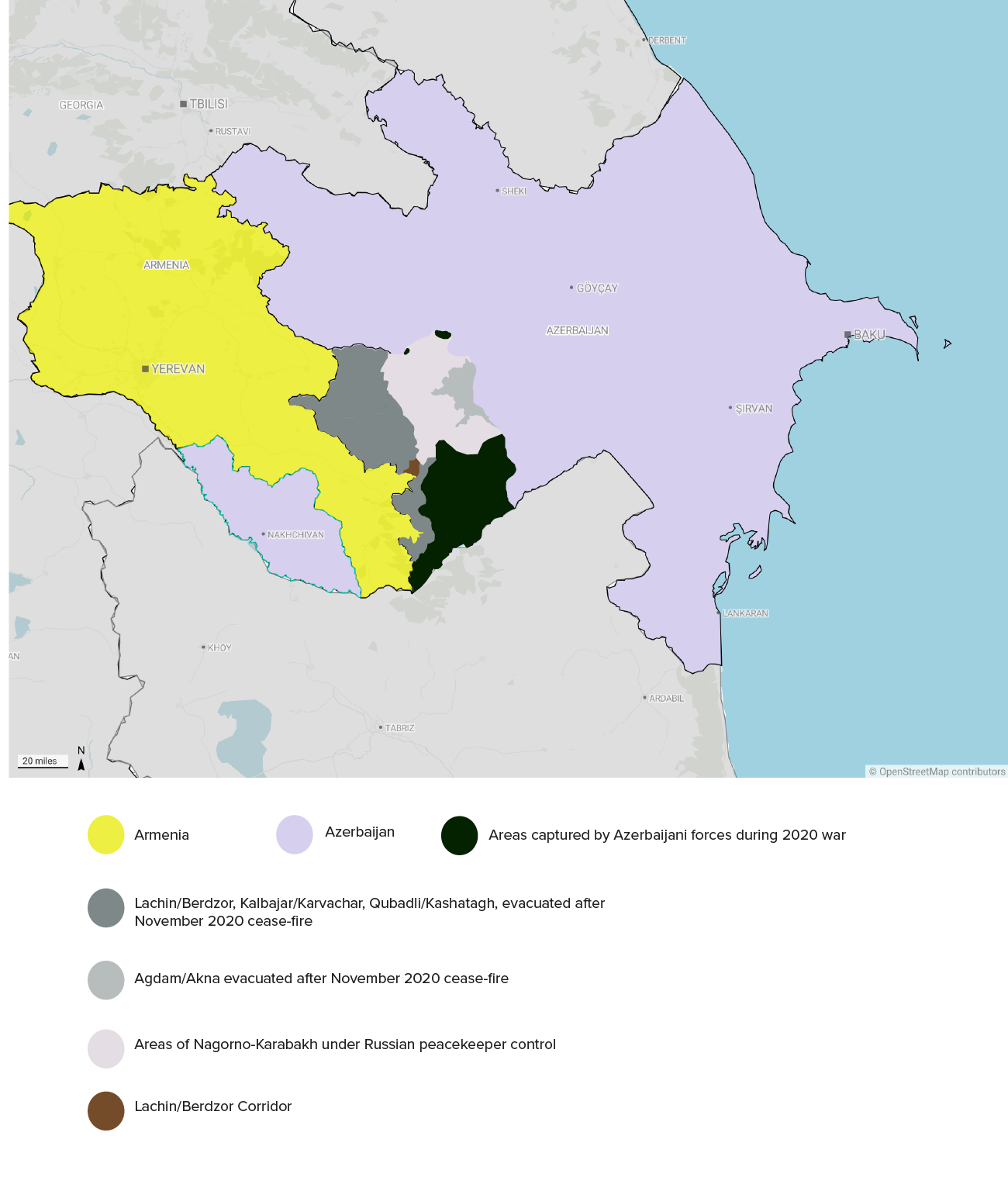

Washington, Paris, and Moscow held cease-fire negotiations on multiple occasions during the war. The Kremlin’s mediation proved effective in the end, largely favoring Azerbaijan and consolidating Baku’s gains. In addition, nearly 2,000 Russian peacekeepers were deployed in areas still under NKR control, which amounted to about two-thirds of the former NKAO. The remainder was either already under the control of Azerbaijani forces or would be relinquished in the weeks following the cease-fire.[33] Azerbaijan thus reversed a quarter of a century of Armenian control over wide swaths of territory in and around the disputed region. Thereafter, a single highway, overseen by Russian forces, would be the only link between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Situation on the ground after 2020

2021–2023: Still Some War, Still No Peace

A number of developments have marred the conclusion of a lasting peace between Yerevan and Baku since 2020. Clashes have continued from time to time.[34] Starting from May 2021, Azerbaijani forces have carried out incursions into Armenian territory, keeping roughly 50 square miles under occupation as of this writing.[35] The province of Syunik in Armenia’s south has been particularly vulnerable, as have other eastern bordering areas. Besides blocking a major highway, dividing villages, cattle rustling, kidnapping, and other events which have created an atmosphere of insecurity, Azerbaijan conducted two large-scale military operations into Armenia, one on November 16, 2021 and one on September 13–14, 2022.[36] The Azerbaijani government argues that the border with Armenia is not demarcated and that no incursions can therefore be determined.[37] Moreover, it claims that Armenian forces have themselves conducted raids or mining operations in Azerbaijan on a regular basis.[38]

Meanwhile, in Nagorno-Karabakh itself the situation was mostly stable, barring a few violent episodes,[39] until the establishment of the blockade of the one highway linking the territory with Armenia and the rest of the world. From December 12, 2022, movement across the Berdzor or Lachin Corridor was partially or wholly blocked, at first by government-directed environmental activists, later by Azerbaijani border security forces.[40] Russian peacekeepers and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) had some opportunities to bring in food or medicine and transport individuals on occasion. However, the estimated 120,000 people living in Nagorno-Karabakh were almost entirely deprived of outside goods, including food and medicine, regular electricity, heating, water, and fuel supplies.

The final assault took place on September 19, 2023, following claims from the Azerbaijani side of casualties from landmines planted by Armenians, framing the attack as an “anti-terror” measure.[41] With no response from the Russian peacekeepers, the remaining Artsakh or Nagorno-Karabakh Republic authorities gave in within 24 hours. In the following days, almost the entire population left the territory—cars lining up on the now-open highway filled the airwaves for days on end.[42] What was usually a two-hour drive turned into an odyssey of 36 hours or more for thousands of families, accompanied by reports of injury, hunger, and death (exacerbated by the explosion of a fuel depot—gas was brought in after many months of blockade[43]). The Armenian government eventually documented the entry of over one hundred thousand individuals, characterizing the process as ethnic cleansing.[44] The Azerbaijani government maintains that they left of their own accord and are free to continue living in their homes, as long as they accept Azerbaijani citizenship.[45] There might be as few as 50 or as many as one thousand Armenians left, being visited by the ICRC on a regular basis.[46] Former Nagorno-Karabakh leaders have meanwhile been arrested and are awaiting trial in Baku.[47]

A service member of the Russian peacekeeping troops stands next to a military vehicle at the Dadivank, an Armenian Apostolic Church monastery, located in a territory which is soon to be turned over to Azerbaijan under a peace deal that followed the fighting over the Nagorno-Karabakh region, in the Kalbajar district November 15, 2020.

Yerevan and Baku continued to remain committed to a peace deal. Two parallel tracks of diplomacy developed in that respect, one with Russian mediation and one with Western mediation—both the US and the EU.[48] Officials from the foreign ministries and the top leadership of both countries met under the auspices of Moscow, Brussels, and Washington on a number of occasions between 2021 and 2023. Though ostensibly pursuing the same aim, the Western and Russian counterparts have differing interests, with no coordination of their activities.[49]

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 widened the gap across the geopolitical centers of power. The mediating parties at times openly disapproved of one another. For example, one of the most tangible outcomes of the mediation was the establishment of a civilian mission by the EU of monitoring the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan—but only from the Armenian side.[50] This prospect did not sit well with Moscow, as neither did Armenian outreach to the West in general.[51] Soon after the final assault on Nagorno-Karabakh on September 19, 2023, a report revealed that the US, EU, and Russian officials met in secret in Istanbul prior to that attack.[52] Channels of communication may have been kept open, but it became evident that diplomacy collapsed with the push made by Baku and the declaration of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic’s dissolution.

Implications and Outlooks

A few components stand out in assessing Nagorno-Karabakh historically, its development over the past few decades, and the events of the immediate past few years. The engagement of the US with the region in particular has some challenges to consider ahead.

Humanitarian Issues

The most pressing concern arising from the latest developments is humanitarian aid. Over 100,000 Armenians fled Nagorno-Karabakh in the week following the final assault on September 19, 2023, including families with children, people with disabilities, and other vulnerable populations.[53] Housing, food, healthcare, schooling, and all of their accompanying challenges have been taken on by the government of Armenia as well as the Armenian Diaspora around the world.[54] The international community has stepped in as well, with pledges and engagements by the UN, EU, and others.[55] USAID allocated $11.5 million—the head of the agency, Samantha Power, who has a checkered past relationship with Armenia, made the announcement on a visit to the country in the week following the attack.[56] Four million dollars were declared in addition at the end of November.[57] A Disaster Assistance Response Team was also sent by USAID as support.[58]

The outlook for the large number of refugees, in a country of three million, is uncertain as of this writing. As in the episode of the 1990s when there had been a flow of Armenians displaced from parts of Nagorno-Karabakh and the rest of Azerbaijan, some of the 100,000 may end up moving abroad, either joining family or given asylum by foreign governments.

There is very little data about Armenians remaining in Nagorno-Karabakh. The UN office in Azerbaijan and the International Committee of the Red Cross have conducted visits and monitored the area, which is reported as largely deserted.[59] The government of Azerbaijan has begun a reintegration initiative, launching a website in four languages to register those Armenians who are willing to take on Azerbaijani citizenship.[60]

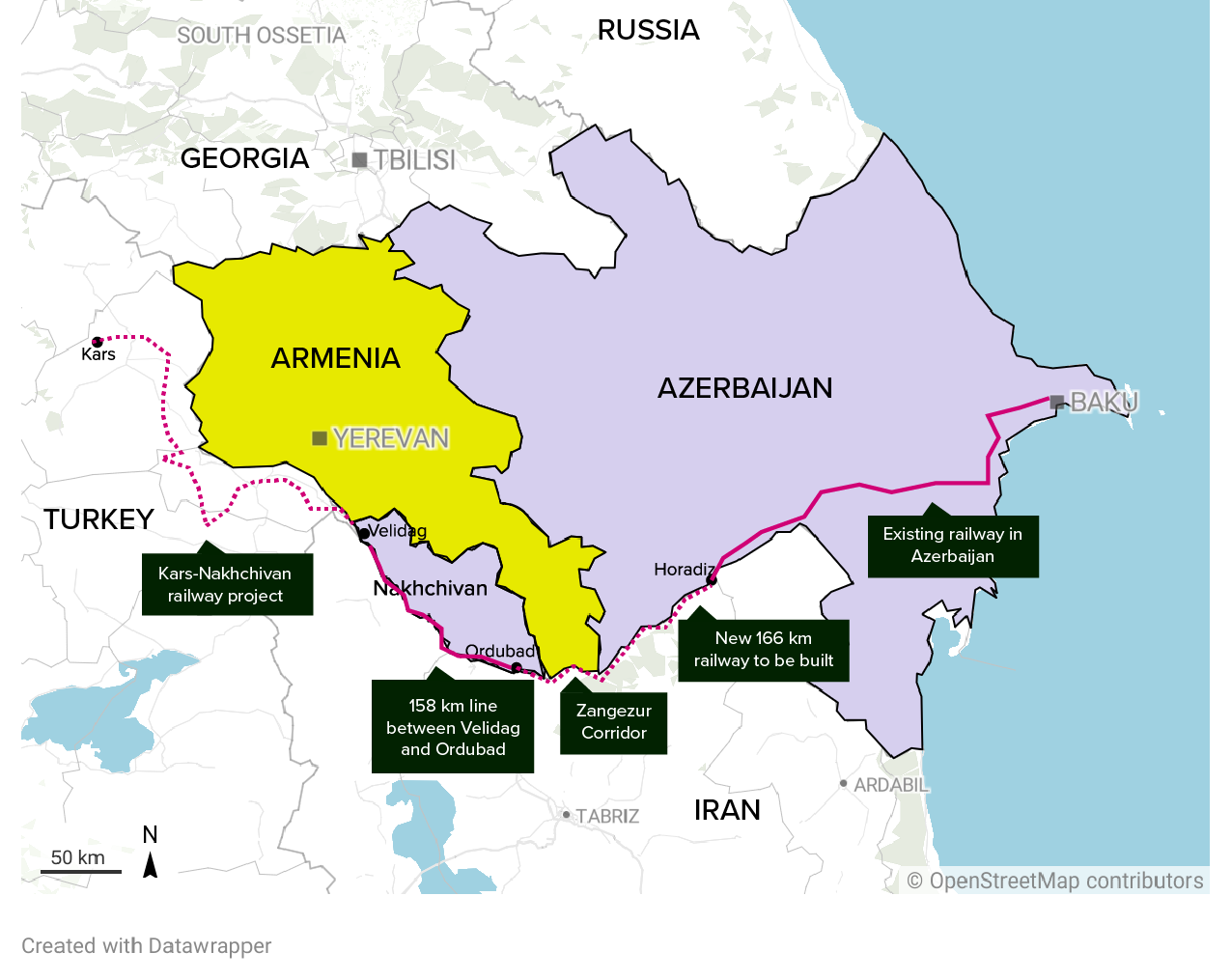

Zangezur Corridor

Among the most salient unresolved aspects of the outcome of the Second Karabakh War relates to transportation infrastructure. According to the cease-fire agreement of 2020, the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan would be given access to the rest of Azerbaijan —“unobstructed movement of persons, vehicles and cargo in both directions,” under the supervision of Russian border security forces.[61] Yerevan has consistently interpreted that clause as a general expectation of opening all borders for all the states in the region, each in charge of its own territory. Baku has suggested extraterritorial sovereign rights over what has come to be called the Zangezur Corridor.

Zangezur Corridor and Potential Connections

Zangezur can be a loaded toponym, evoking nationalist Azerbaijani readings of history and echoing Azerbaijani discourse about Armenians having moved to the Caucasus only in recent times, in the 19th century.[62] The panhandle region in question is also commonly called Zangezur in Armenian, although its more formal name as a province of the country is Syunik. Irredentist claims to Syunik and other parts of Armenia have been prevalent in Azerbaijani media since 2020.[63] The Azerbaijan Refugee Society was renamed the Western Azerbaijan Community in 2021, pushing forward the idea of the return of Azerbaijanis who fled Soviet Armenia at the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s.[64] Armenian refugees from Soviet Azerbaijan during the same period, meanwhile, are not accorded equivalent consideration. This is another example of mirroring discourse mentioned earlier—“Western Azerbaijan” reflects “Western Armenia,” which is a term common in Armenian discourse to refer to territories in central and eastern Turkey that had been populated by Armenians since antiquity until the genocide during the First World War.

There are serious concerns of an armed incursion on a large scale by Azerbaijani forces beyond Nagorno-Karabakh in order for Baku to secure a passage across Syunik/Zangezur.[65] Iran shares concerns about such a prospect as well and about the corridor as such, as it could risk its sole land border with Armenia.[66] The road through Syunik/Zangezur is an important trade route for Iranian goods. It avoids passage through Turkey—a Western, NATO ally—and Azerbaijan, which has close security ties with Israel, rumored to be a base of intelligence operations directed against Iran.[67] As such, Tehran and Baku have a rocky relationship which has seen ups and downs since 2020 in particular.[68] However, recent talk of an alternative or supplemental route through Iran to connect with Nakhchivan may allay broader regional security concerns.[69]

The strongest indicators of increased regional and global attention to Syunik/Zangezur have been the frequent visits by diplomats and international engagements with the area, going so far as the opening of an Iranian consulate in the provincial capital, Kapan.[70] Russia too plans on establishing a consulate there, as does France.[71]

A line of cars, including cars packed with personal belongings seen along the highway to Goris, Armenia.

Regional and Global Security Dynamics

The most recent developments in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh have important implications for the future of regional and global security dynamics. The deployment of Russian peacekeepers at the end of the 2020 war could have been a further move toward securing an enduring Russian influence over the South Caucasus. Since the full-scale assault on Ukraine, however, Moscow’s attention has been drawn away from the region. What some observers saw as inaction in response to the events of September 2023 might have reflected Russia’s inability to act as a powerful regional player by brokering effective conflict management between two small states in its neighborhood.[72] On the other hand, Russia could have been unwilling to aid Armenia, a treaty ally, due to a belief that Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan had sought closer ties with the West.[73] Russia may be reevaluating its bilateral relationships considering the strategic folly in Ukraine, potentially seeking closer alignment with Azerbaijan as relative power shifts toward Baku in the region. Azerbaijan has, meanwhile, positioned itself as a major supplier of energy to Europe as the continent diversifies away from Russian gas.

Besides Russia, Turkey, Iran, and Israel are the other main regional players involved in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Turkey and Azerbaijan have strong ties, based, among other things, on a shared pan-Turkic identity.[74] As mentioned, going beyond diplomatic or rhetorical support in preceding decades, Turkey provided Azerbaijan direct military aid in the 2020 war—including such valuable resources as Bayraktar drones and current and long-standing military advising and training—which very likely contributed to its victory.[75]

Iran and Azerbaijan have had a tense relationship since the end of that conflict, highlighted on both sides by military posturing near their shared border, charges of interference in domestic affairs, and fears about collusion with each other’s external adversaries.[76] Iran therefore prioritizes close ties with Armenia to balance against Azerbaijan. Tehran perceives Baku’s ambition to establish a transport corridor across Syunik/Zangezur as a check on its own geo-economic influence in the region. Iran sees Armenia as a gateway to Russia and other Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) markets. Iran and the EAEU have a free trade agreement that went into effect in 2019.

For its part, Israel has found a lucrative arms market in Azerbaijan. Its weapons and kit have accounted for nearly 70 percent of Azerbaijan’s military imports in the five years preceding the 2020 war.[77] Iran’s move to build stronger ties with Armenia may correlate with Israel’s tilt toward Azerbaijan over the past few years. As of this writing, it is too early to tell how the war with Hamas impacts the level of Israeli engagement in the South Caucasus.

The latest Azerbaijani assault on Nagorno-Karabakh followed by the muted Russian response signals the shifting bases of power in the South Caucasus. This offers policymakers in Washington, Paris, and Brussels opportunities to take the lead in trying to establish lasting peace and stability in the region. The activities of the Minsk Group remained the primary mechanism to find a long-term solution. However, both the dismissiveness of the Minsk Group by the authorities in Baku following 2020 and Russia’s status as a Minsk co-chair complicate things while there is no end in sight to the Ukraine war.[78]

Nagorno-Karabakh was one of the few issue areas where Moscow and the West had active and consistent collaboration. It could once again play that role, independent of disagreements over Ukraine or other things. Issue linkage of resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute with, for example, normalizing relations between Armenia and Turkey was never useful in the past. Yerevan and Ankara have seen little progress in their relations since 2020, even with some efforts by both sides. Likewise, any other issue linkage on Nagorno-Karabakh would likely wreck any possibility of reaching a permanent settlement. That should serve as a point of caution for all parties involved.

The US has endeavored to develop strategic partnerships with both Armenia and Azerbaijan ever since the two countries gained independence in the early 1990s. US bilateral relations unsurprisingly revolve around democratic development and economic growth. The US has long supported Azerbaijan in developing and expanding access to Western markets for its energy resources.[79] In fact, crude oil is the single largest import from Azerbaijan to the US. Washington could use its influence over global financial and trade markets and impose sanctions to pressure Baku into committing to a solution on Nagorno-Karabakh agreeable to all stakeholders.

Any effective economic measures against Azerbaijan, however, would require European cooperation with the US, which may be difficult to achieve. Baku has gained increased geo-economic clout since Europe’s decision to divest away from Russian fossil fuels, as Azerbaijan has become a crucial alternative supplier to the continent.[80] In July, 2022, the EU concluded a deal with Baku to double gas imports by 2027.[81] The EU is also Azerbaijan’s main trading partner and its leading investor in the non-oil sector contributing to the diversification of its economy. There is currently a lack of consensus within Europe over how, or whether, to respond to Azerbaijan’s imposition of a military solution to the conflict. Therefore, it is an unlikely target for Western economic warfare for the foreseeable future. While many European state leaders and EU policymakers have publicly condemned Azerbaijan, they have not taken concrete action against it.[82] Instead, the bloc appears more interested in bolstering its image as a neutral mediator between all sides, while Azerbaijan has preferred to take decisive action on its own.

Under these circumstances, the EU has taken steps to increase support for Armenia. A week after the Azerbaijani assault, the EU announced it would provide approximately $5.4 million in humanitarian aid to assist people displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh.[83] The bloc is also considering a visa liberalization scheme with Armenia akin to its existing arrangements with other former Soviet republics as well as additional support through the European Peace Facility, a special fund to support peacekeeping operations and defense capacity-building in EU partner countries.[84] Finally, Brussels and Yerevan have agreed to expand the EU’s monitoring mission on the Armenian side of the border as an early warning system against potential future Azerbaijani aggression.[85]

A vehicle drives along the road leading from Armenia to Azerbaijan’s Nagorno-Karabakh region, near the village of Tegh, Armenia September 21, 2023.

Denying Recognition and Self-Determination

Two aspects of public international law are noteworthy when assessing the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

The first aspect is the principle of national self-determination. This has been a woolly concept ever since its inception by President Woodrow Wilson in his Fourteen Points in 1918.[86] The world is not neatly divided into readily identifiable ethno-national populations living on territories with clear borders. It was this same manner of thinking that led to the phenomena of titular nationalities of the USSR and the territorial challenges derived from them discussed above.

At the same time, there are indeed populations with distinct cultural, religious, ethnic, or political identities which, through violence or otherwise, have established sovereignty or degrees of autonomy. One need not look far for an example—the Thirteen Colonies themselves struggled for self-rule at the end of the 18th century. The 20th century had major upheavals like the two world wars plus movements for decolonization lasting decades, some marred by tragic violence and others displaying stable transitions of power. The engagement of the international community with such processes allows for mechanisms that minimize the risk of war and human catastrophe.

The instrumentalization of recognition can add to the complexity of disputes—for example, the partial recognition of Kosovo or Abkhazia, or the nonrecognition by the US of the incorporation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into the USSR. However, neither recognition nor self-determination necessarily imply full and exclusive territorial control. Both recognition and self-determination as concepts and practices can have a wider scope, ensuring human rights and dignity without compromising security or sovereignty. There does not necessarily have to be a zero-sum, exclusive outcome in the interplay between self-determination and territorial integrity. Given the political will, human rights can be placed at the center of resolving conflicts, with due compromise on distributing power and, over time, creating a shared identity.

This point drives to the heart of the matter of the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh and, indeed, numerous other conflicts in the Balkans, the Middle East, and around the world. How can diverse ethno-national or religious communities perceive and acknowledge a space as shared? What kind of practices can allow for the accommodation of all present stakeholders? How can rights and powers in defined territories be distributed inclusively?

Explosives deactivator walks over a deactivated Azerbaijani rocket in the outskirts of Stepanakert, capital of Nagorno Karabakh.

Normalizing the Use of Force

Second, the principle of refraining from the use of force is worth examining in this regard. Enshrined in the UN Charter,[87] it has evidently been greatly compromised, with impunity. This fall-out from Nagorno-Karabakh may arguably have the most far-reaching implications for global security.

For centuries, warfare was considered a legitimate foreign policy tool within the practice of European states.[88] This idea was eroded after the First World War but did not become codified as illegitimate until 1945.[89] Unless a state is engaged in self-defense or unless endorsed by the UN Security Council, governments are prohibited from the use of force. The concept of Responsibility to Protect (R2P) has added some nuance in recent decades, allowing for forceful intervention for humanitarian ends, although it remains somewhat nebulous and controversial.[90]

The principle of nonuse of force has certainly been violated on a number of occasions over the past 75 years and more. Indeed, the US itself arguably disrupted it the most since the end of the Cold War, leading operations and invasions in Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya. The wars in Georgia and Ukraine initiated by Russia have, for their part, been the most egregious examples of disregarding the norm in the former Soviet space.

Besides being UN members, Azerbaijan and Armenia also pledged on multiple occasions not to resort to force in pursuing a resolution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Baku reneged on its promise in 2020 and has continued to do so since.

If left without tangible reactions and future disincentives from the international community, including the US, Azerbaijan’s actions would serve as evidence for regimes not just in the post-Soviet space that use of force could have net-positive payoffs.

Moreover, Azerbaijan frames its actions as adhering to international law because it was restoring control over its internationally recognized territory. Perhaps the closest analog to this logic is the discourse in China vis-à-vis Taiwan. China may very well interpret Western inaction toward Azerbaijan as a green light to try to forcibly reintegrate Taiwan soon. The crucial difference here is that the US has existing security commitments, albeit ambiguous, to defending Taiwan. Armenia’s – and later Russia’s – commitments to Nagorno-Karabakh could be characterized along those same ambiguous lines. Northern Cyprus is a similar case as well.

Conclusion

Before Azerbaijan’s fatal assault against Nagorno-Karabakh in late September 2023, the small unrecognized republic had proven itself a remarkably durable entity. For nearly 30 years it endured in limbo, having managed to create basic institutions and establish territorial control while its very existence was constantly under threat by Baku. While the First Karabakh War yielded the birth of a de facto independent state, it thereafter had always been in a precarious position for two main reasons—the limited geographic reach via the Republic of Armenia and its lack of international recognition and, thus, sovereignty as a state. That the opposing sides and powerful external actors failed to reach a permanent settlement in the many years of “no war, no peace” only made the NKR’s situation more difficult. The Second Karabakh War resulted in reversing the gains of the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians, setting up conditions on the ground which have favored Azerbaijan since autumn 2020.

Azerbaijan’s latest attacks reflect the changing power dynamics in the South Caucasus and beyond. In a region in which Moscow has long asserted privileged interests since Romanov times and in the Soviet and independent Russian eras, it is evident that Azerbaijan is now taking matters into its own hands by using force and with the stronger backing of regional power Turkey. Baku’s assertiveness indicates increased self-confidence, due also to its newfound role as a major alternative hydrocarbon supplier to Europe, itself now divested of Russian oil and gas. While Russia seems too brittle to divert any attention or resources away from its Ukraine debacle, recent developments in the South Caucasus may also suggest it is considering switching sides in the long running conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. It may, however, be too early to tell if Russia is reevaluating its existing alliances and partnerships. For its part, Azerbaijan’s actions have been opportunistic, exploiting Russia’s weakened position in the region.

Given this geopolitical context, the US has limited options moving forward. It should consider extending its diplomatic footprint to take advantage of the shifting power dynamics in the region. It should also support an enduring international monitoring mechanism to safeguard against renewed escalation along the shared border of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Most importantly, the US should work with and through its European partners to reduce human suffering and improve the quality of life of those displaced by violence. These are all worthwhile endeavors in line with US values and interests.

No comments:

Post a Comment