by Sungki Hong and Hannah G. Shell

Currently, automation is occurring more in service and manufacturing positions. It is one factor that contributes to labor market polarization, or the disappearance of middle-income, routine task type jobs in the U.S.[1] Despite a strong labor market, fear of job loss from automation is common. Some parents with young children already worry that robots will take all potential jobs for their children in the near future.[2]

Automation in the U.S.

Automation can impact the labor market in several ways. One way is through job loss. Automation means fewer jobs for laborers in the short term, which could increase the unemployment rate. In the long term, laborers will either exit the labor force or seek new skills to work in a different occupation.

The short-term impact of automation is not directly observable, but two economists at the University of Oxford, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, attempted to quantify jobs that are at risk in a 2013 article about automation.[3] The researchers used a machine-learning algorithm to estimate the probability that an occupation will become automated in the next few decades. The probability is calculated based on three major factors of the occupation: perception and manipulation, creative intelligence, and social intelligence. The result can be interpreted as the likelihood that engineers will be able to produce machinery that performs tasks required in each occupation.

The economists found that 47 percent of jobs in the U.S. are at risk of becoming automated. Jobs that are repetitive or routine-intensive have the highest probability of this happening. The economists predicted that the transportation and logistics occupations, as well as the office and administrative support occupations, will lose the most jobs to automation over the next decade or so.

Not all jobs are at risk for automation. Occupations that require technical procedures, persuasion, social intelligence and creative intelligence are less likely to become automated. Community and social services occupations, along with science, engineering, mathematical and artistic occupations, are least likely to become automated in the immediate future, although they are not entirely immune to automation.

The Oxford economists predicted that automation will occur in waves, first replacing routine tasks, then slowing as engineers reach a technological plateau. A good example, provided by Frey and Osborne, is that paralegals and legal assistants (which are considered relatively low-skill, routine-based occupations) are seeing their jobs quickly becoming automated; however, it will be a long time before computers are advanced enough to replace lawyers (whose jobs are considered high-skill, nonroutine).

Impact on the Eighth District

Occupational employment is not evenly distributed over regions, so certain metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) and regions of the country will experience more impact from automation depending on the occupational mix. To examine the impact that automation may have on the St. Louis Fed’s District,[4] we’ve merged the Frey and Osborne probabilities of automation with the Census Bureau’s 2017 Occupational Employment Statistics data set, using employment data on the MSA level.

Compared with Frey and Osborne’s results, our employment data yield a slightly higher estimate of the number of jobs at risk for automation. We found that 57 percent of jobs could be automated on the national level, while 60 percent of jobs in the District have potential to be automated in the next two decades.[5]

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the proportion of jobs in each District MSA that is at risk of automation. The figure gives us an idea of which MSAs will be most impacted across the District. The proportion of employment in automatable occupations is inversely correlated to the size of the labor market in District MSAs.

The MSA with the highest proportion is Hot Springs, Ark. (64 percent of 28,330 employees), while the MSA with the lowest is Little Rock-North Little Rock-Conway, Ark. (56 percent of 326,240 employees). The smaller MSAs tend to have more employment concentrated in sales, production and food preparation occupations, which all have a high probability of automation. From this figure, we can see that smaller MSAs in the District may feel the impact of automation more in the next few decades.

Figure 2

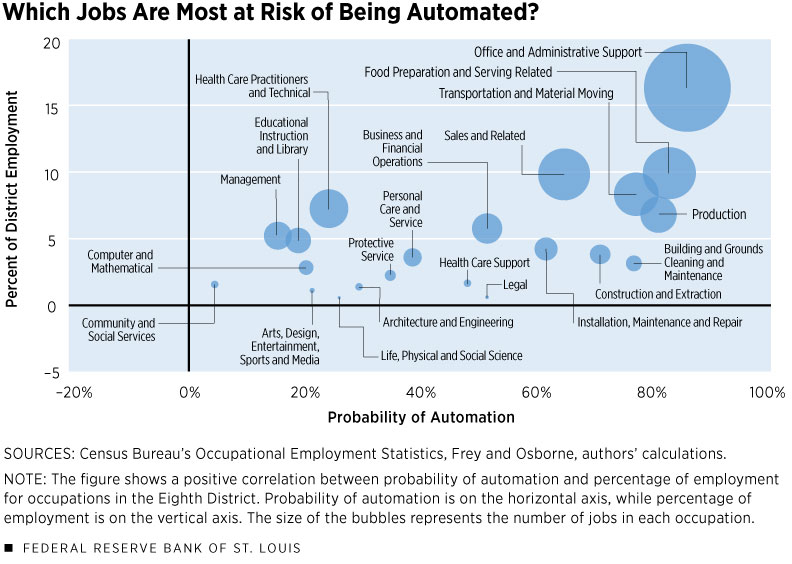

In the District overall, the occupation that is most likely to be impacted by automation is office and administrative support. Figure 2 shows which other occupations in the District will be heavily impacted by automation. The horizontal axis displays an occupation’s probability of automation as estimated by the Oxford economists, and the vertical axis represents the occupation’s employment as a percentage of District total employment. The bubbles are sized according to an occupation’s total employment in the District.

The graph shows a positive correlation, meaning many of the highest-employment occupations in the District also have a high probability of automation. Office and administrative support, food preparation and serving, sales, and transportation occupations are all big sources of employment in the District. Because many of these occupations involve routine tasks, they are likely to be automated over the next few years.

The occupations in the District with high employment and low probability of automation are in health care, business and financial operations, education, and management occupations. These jobs all require some degree of greater human intelligence and social interaction or else they involve nonroutine tasks that computers are unlikely to be able to perform.

Conclusion

In this article, we have looked at how automation would impact jobs in the Eighth District. We found that the jobs in the District are more exposed to risk of computerization than the nation-wide average. By examining data on the MSA level, we saw that smaller MSAs have higher probabilities of automation. Also, high employment occupations - such as office and administrative support, food preparation and serving - face a higher probability of automation.

These results should be interpreted carefully. The probability of automation does not equal the probability of job loss. There are many additional factors that we would need to account for to measure job loss. For example, these estimates do not include the equilibrium effect of how easy or hard it will be for a displaced worker to find a new job in other industries when replaced by a machine. Also, we do not consider whether the cost of research and development investment for computerization is lower than the cost of labor.

The full impacts of automation remain hard to quantify. Job loss is one potential outcome, but automation could also result in job polarization and lead to increased income inequality.

Endnotes

See Dvorkin and Shell for a discussion of labor market polarization and its impact on the District.

See Samuel.

See Frey and Osborne.

Headquartered in St. Louis, the Eighth Federal Reserve District includes all of Arkansas and parts of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee.

Risk of automation does not mean these jobs are going to disappear in the next two decades. Rather, risk of automation measures how likely that an occupation will be impacted by automation.

References

Dvorkin, Maximiliano; and Shell, Hannah. Labor Market Polarization: How Does the District Compare with the Nation? Regional Economist, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2017:Q2, pp. 22-23. See https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/second-quarter-2017/labor-market-polarization-how-does-the-district-compare-with-the-nation.

Frey, Carl B.; and Osborne, Michael A. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerization? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 114, January 2017, pp. 254-80. See https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019.

Samuel, Alexandra. How You Can Raise Robot-Proof Children. The Wall Street Journal, April 26, 2018. See https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-you-can-raise-robot-proof-children-1524756310.

No comments:

Post a Comment