BY KEITH JOHNSON

India and the United States hope to reach a limited trade agreement in time for U.S. President Donald Trump’s first visit to the country this month, but experts question whether the larger strategic relationship both sides have cultivated for more than a decade is being sacrificed to Trump’s niggling trade demands.

On the one hand, U.S. administrations beginning with George W. Bush and continuing under Barack Obama have indicated they need India as a strategic partner to help counter China’s growing influence. On the other hand, under Trump, Washington is now publicly browbeating India over the price of walnuts and Harley-Davidsons.

“The administration does not have an integrated policy toward India or anyone else for that matter,” said Ashley Tellis, an India expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

U.S. national security officials have their own view of India’s place in America’s Indo-Pacific strategy and have built on the Obama administration’s efforts with closer defense cooperation, especially in the navy, and through increased arms sales. But U.S. trade officials, obsessed by trade deficits, have their own narrow agenda focused on prying open parts of the Indian market—a view entirely divorced from the bigger picture.

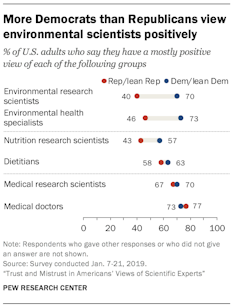

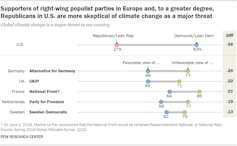

Global Threats. Pew Research Center

Global Threats. Pew Research Center Twitter.

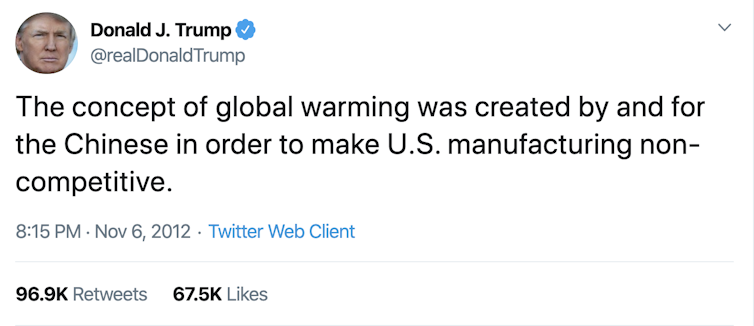

Twitter.