Mathieu Boulègue

Russia’s policies for the polar regions overlap and are increasingly becoming militarized, as the perception of threats to Russian national interests grows. This has direct consequences for other polar nations and for NATO and its allies.

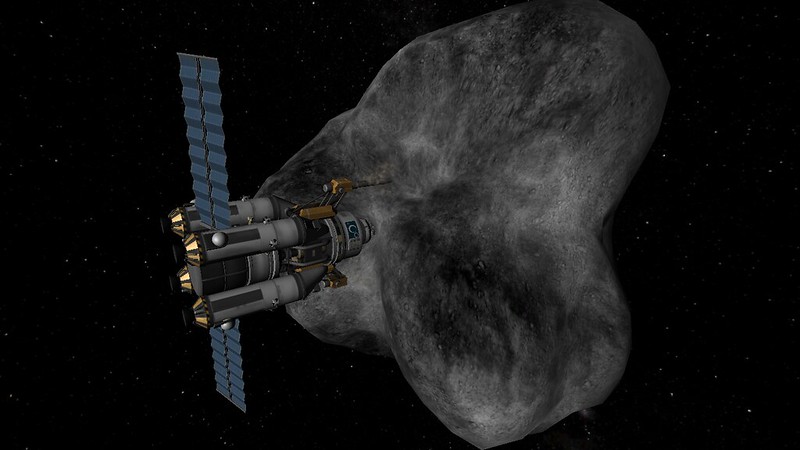

In the Arctic, a fear of encirclement by NATO and its allies informs this posture – heightened by worsening relations with the West over Russia’s renewed war against Ukraine and potential NATO expansion. Another key Russian goal is to secure control over the Northern Sea Route, amid increased human activity prompted by climate change. In Antarctica, Russia perceives a need to protect its national interests against other state parties to the Antarctic Treaty System.

This paper details the reasons behind Russia’s militarized postures in the Arctic and Antarctic regions. It assesses the North and South Poles as potential theatres for military activity and geopolitical confrontation, and recommends ways to mitigate risks for the US, NATO and their allies.

Summary

Although Russia does not have a defined common approach to the polar regions, its postures in the Arctic and in Antarctica overlap. They are securitized and increasingly militarized, with direct consequences for other polar nations.

In the Arctic, Russia’s main threat perception relates to the fear of encirclement by NATO and its allies. In the context of Russia’s renewed war against Ukraine since February 2022, the Finnish and Swedish applications to join NATO and the likely expansion of the alliance are a case in point. In Antarctica, Russia’s posture relates to protecting its national interests from territorial claims over the continent by other Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) member states.

Moscow views the Arctic as a strategic continuum stretching from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific. The Kremlin’s priorities are to: impose costs on other countries’ access to Russia’s European Arctic; protect the Northern Sea Route; defend North Pole approaches;

remove tensions from the region; and extend Russia’s military capabilities beyond the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF).

Russia is rebuilding its military capabilities and modernizing its regional military infrastructure by using a ‘double dual’ approach: Arctic infrastructure is being used for civilian and military purposes (dual-use), while Russia is also blurring the lines between offensive and defensive intent (dual-purpose).

This ambition to exercise control and denial capabilities beyond the AZRF and the Kremlin’s willingness to push military tensions towards the North Atlantic are increasing pressure on regional navigational chokepoints – namely the Greenland–Iceland–UK and Greenland–Iceland–Norway gaps – and the Svalbard archipelago. Russia also seeks to undermine US strategic dominance in northeast Asia – more specifically, the deployment of US theatre missile defence in Japan and South Korea.

Moscow also has an increasingly securitized understanding of the future of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean. This is reflected in policies aimed at safeguarding Russian national interests within the ATS, as well as those allowing Russia to contest the maritime and naval activities of other states in the Southern Ocean.

Russia’s posture in polar affairs has two main consequences for Arctic coastal states and for the future of the ATS: the need to manage accidents and miscalculations in polar affairs; and increased Russia–China interaction at both poles.

The Russian approach to China’s increasing presence at both poles is pragmatic and compartmentalized. While Russia for now is developing cooperation with Beijing within the ATS, it is much more cautious when it comes to the Arctic, where China’s presence is only tolerated. At both poles, the Kremlin needs to manage Beijing’s attempts to shape the future of polar governance, and take steps to ensure that Russian interests are respected.

Tension and miscalculation in polar affairs must be managed by shaping Western policy around Russia’s increasingly militarized approach to the Arctic and Antarctic regions. Preserving the spirit of ‘low tension’ in the Arctic and stability within the ATS will require careful adjustments from Western policymakers.

This paper recommends that Western policymakers consider Arctic and Antarctic policies as interdependent; understand the Arctic region as a strategic continuum; expand discussions on military security in the Arctic without Russia; and take action to address the lack of transparency around Russia’s actions in Antarctica.

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/KMP5INOQI5GX7PALN6KU44342E.jpg)