MILAN VAISHNAV

While last week’s border skirmishes between India and China sent commentators rushing to Google Maps to locate obscure mountainous locales, the jousting in the Himalayas may prove to be a geopolitical inflection point. On strategic affairs, New Delhi and Beijing have long been at loggerheads, but the former has attempted a tightrope walk of cozying up to the West without alienating the communist regime. That may be about to change. In the wake of the brutal killing of at least twenty Indian soldiers by Chinese forces wielding a medieval mix of stones, clubs, and nail-studded rods, India might be forced to rethink its longstanding policy of strategic hedging.

IT'S THE ECONOMY, STUPID

Yet the foreign policy impact of last week’s high-altitude encounter will turn less on India’s diplomatic and defense maneuvers than on simple economics at home. India’s ability to project power abroad, protect its homeland, and assemble and sustain meaningful partnerships depends on the capacity of India’s political leaders to quickly and competently get its economy back on track. The foreign policy crisis consuming the government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the wake of the border clash—as real and raw as it might be—cannot be resolved unless India first fixes its economic emergency.

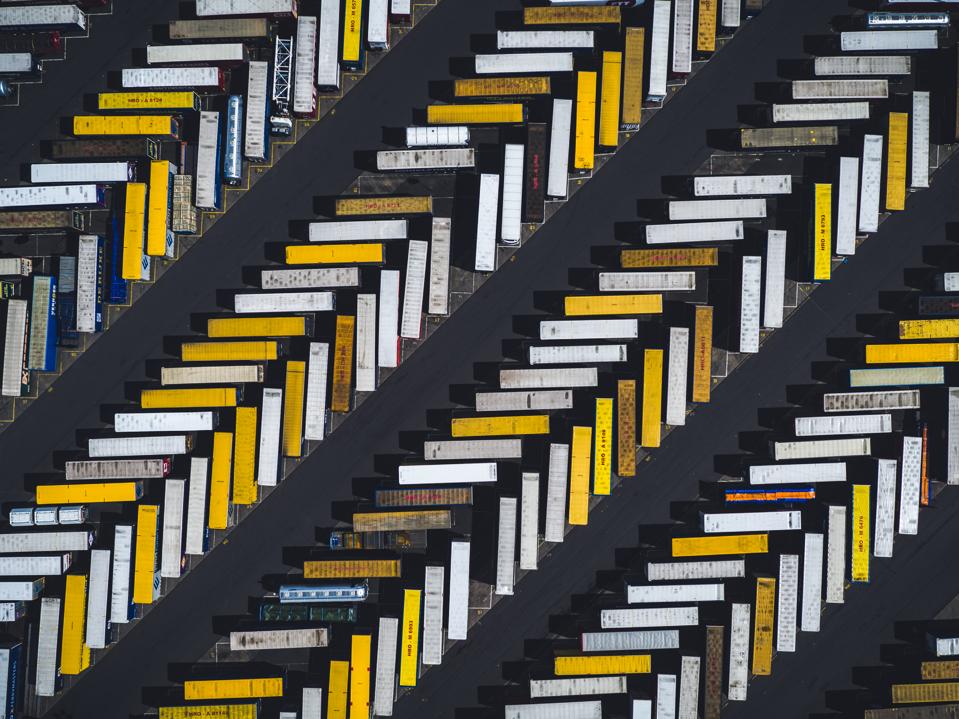

/media/img/2020/06/23/Atlantic_America_slump_v1/original.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/AX5MVQUNYFE3LNVJ46G6SMD4TA.JPG)