Vietnam faces a serious long-term security challenge from China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea, and its response has included efforts to strengthen its military capability, particularly in the maritime sphere. This report assesses the extent of these efforts and looks at how Hanoi has used a widened array of international security relationships to diversify Vietnam’s procurement for its armed forces and coastguard, while also developing its national defence industry. The report argues that international sanctions imposed on Russia in response to the war in Ukraine seem likely to amplify these trends.

Vietnam faces a major long-term security challenge from China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea, despite the two countries’ close economic ties. While bilateral tensions have manifested as a maritime grey-zone conflict, Hanoi is determined to strengthen Vietnam’s military capability to deter Chinese escalation, particularly through what appears to be a maritime anti-access/area denial strategy. It is doing this cautiously and incrementally and, since 2016, equipment procurement has slowed, most probably because of budgetary constraints. Although the Vietnam People’s Army (VPA) is likely to depend on equipment originally supplied by Russia for years to come, for multiple reasons Hanoi has begun to diversify its military procurement and to rely less on Russia. It has already made some limited equipment purchases for its armed forces and coastguard from a range of other international sources, most of them small and medium powers, including Israel, which is now Vietnam’s second-most important defence supplier. Hanoi has also tentatively developed security relations with India, Japan and the United States, but, so far, these larger powers have not supplied Vietnam with strategically important equipment. Vietnam is continuing to develop its indigenous defence industry, often through partnerships with international suppliers. This will allow it to strengthen its capacity to maintain, repair, overhaul and modify major defence equipment and to produce systems for specific VPA requirements. Sanctions imposed on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the subsequent war seem highly likely to amplify these trends. Consequently, integrating military equipment from diverse sources to maximise Vietnam’s capability to deter escalation and contend with grey-zone pressure may become an increasingly important task for the country’s defence industry.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/JSULF2YKRBHFJLQWROW3FQ6FJI.jpg)

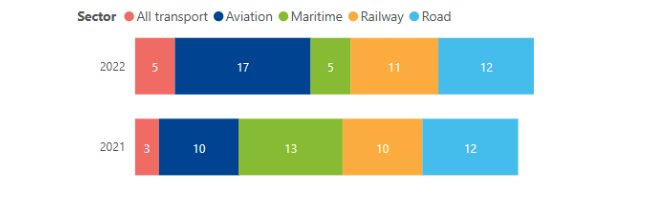

Annual observed incidents in each sector (January 2021 to December 2021, January 2022 to October 2022), source: ENISA

Annual observed incidents in each sector (January 2021 to December 2021, January 2022 to October 2022), source: ENISA