By Abhijnan Rej

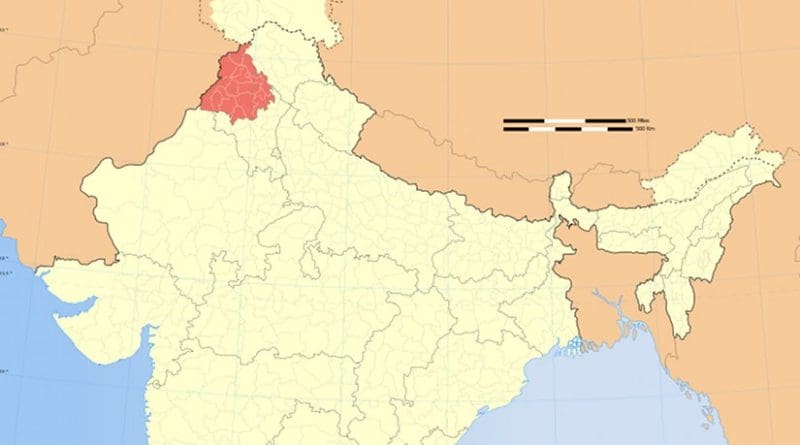

The India-China military crisis in eastern Ladakh entered a new phase over the weekend when the Indian army pushed back an attempt by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to alter the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between the two countries in a new area on the southern bank of Pangong Lake, in the Chushul/Spangpur gap, according to defense journalist Nitin Gokhale. An Indian government statement issued earlier today notes that on the intervening night of August 29 and 30, the PLA “carried out provocative military movements” there.

The India-China military crisis in eastern Ladakh entered a new phase over the weekend when the Indian army pushed back an attempt by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to alter the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between the two countries in a new area on the southern bank of Pangong Lake, in the Chushul/Spangpur gap, according to defense journalist Nitin Gokhale. An Indian government statement issued earlier today notes that on the intervening night of August 29 and 30, the PLA “carried out provocative military movements” there.

It added that “Indian troops pre-empted this PLA activity… [and] undertook measures to strengthen our positions and thwart Chinese intentions to unilaterally change facts on ground.” No casualties – or other details – are available at this moment.

Beijing has refuted the Indian statement. Reacting to a question, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian claimed that “Chinese border troops always strictly abide by the LAC. They never cross the line.”

Three things are striking about this latest development.