by Sebastien Roblin

Here's What You Need to Know: India could probably gain a lot through deepened cooperation even while stopping short of needlessly provoking China.

Here's What You Need to Know: India could probably gain a lot through deepened cooperation even while stopping short of needlessly provoking China.For decades, the Indian Navy has been the dominant regional power in the Indian Ocean, and has even boasted a carrier aviation capability that was nearly unique in Asia.

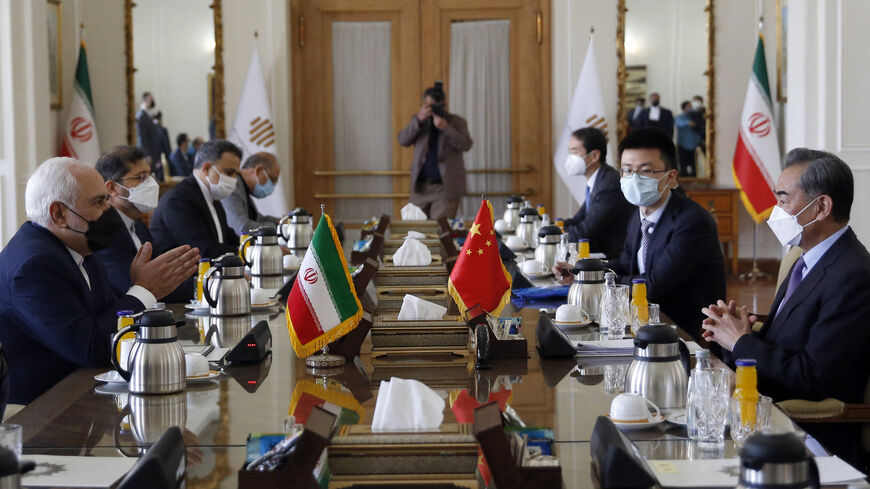

But as outlined in a report by the Center for New American Security (CNAS), the growth of Chinese military power in the last two decades has dramatically eclipsed India’s own attempts to modernize and expand its forces—particularly in the maritime domain. This is problematic due to New Delhi’s tense relations with Beijing since a 1962 border war.

While the vast majority of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is naturally concentrated on the Pacific Ocean, in recent decades it has struck agreements giving it access to bases and ports in Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. It has also established a military base in. Together, these form a ‘String of Pearls’ designed to envelope India geographically. The PLA Navy has also increasingly dispatched ships on patrols of the Indian Ocean, including a nuclear-powered attack submarine that could be used to hunt India’s new ballistic missile submarines.

While India still retains numerical superiority in the Indian Ocean today, China is laying the groundwork to rapidly expand its presence in the region if desired.