Phillips Payson O’Brien

What happens on the battlefield is rarely the thing that decides a war. Normally, the preparations beforehand determine what happens when the fighting begins—and these preparations are what settle the outcome of the war itself. This truth is playing out along the roads and in the towns of Kharkiv Oblast, the province that includes Ukraine’s second-largest city. The stunningly swift advance of Ukrainian forces, which started around September 1 and sped up soon after, has easily been the most dramatic—and for Ukraine and its supporters, the most uplifting—episode of the war since the current Russian invasion began on February 24. In a few days the Ukrainians liberated about as much territory as Russia had captured in a few months, while causing the disintegration of Russian forces around Izium, Kupyansk, and other logistically vital cities. From the outside, Ukraine appears to have changed the whole complexion of the war.

This stunning Ukrainian advance was anything but sudden. It resulted from a patient military buildup, excellent operational security, and, maybe most important, the diversion of some of the Russian army’s most powerful units from Kharkiv Oblast itself. The overall planning by the Ukrainian government and armed forces worked well on so many levels that it produced one of the greatest military-strategy successes since 1945.

Only a week ago, the most important engagement for Ukraine appeared to be the battle for Kherson. For months, President Volodymyr Zelensky, his senior aides, and other Ukrainian sources had publicly proclaimed the goal of liberating the politically and strategically important southern city and the rest of the Russian-controlled territory on the west bank of the Dnipro River. Not only did the Ukrainians discuss the upcoming campaign, but they took all the necessary preparatory steps. They used their most effective long-range weaponry, including the American-supplied High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, to destroy bridges, ammunition depots, and other targets up and down the Russian lines near Kherson. These logistical attacks suggested that the Ukrainians would focus on this area for the rest of the summer.

In response, Russian President Vladimir Putin—who seemed to agree that the city was the highest priority—did exactly what the Ukrainians hoped: He rushed forces to the area. Evidence exists that some well-armed Russian units were redeployed there from the Russian-occupied Donbas in the east.

By some criteria, Kherson was a much better place than the Donbas or Kharkiv Oblast for the Ukrainians to engage the Russians. The southern city is deeper into Ukraine and farther from the sources of Russian supplies. Supply lines into Kherson depend on only a few crossings over the Dnipro. Ukrainian strategists who want to keep wearing down the Russian army would rather see its most powerful parts in Kherson than the Donbas, which is much easier for Russia to protect by air.

On August 29, the Ukrainians stepped up their attacks around Kherson. Though they made some incremental advances at first, the battle seemed to be only a somewhat accelerated version of the attritional warfare that has been under way since April. Stories started circulating that the Ukrainians were being cautious in their plans and that U.S. officials had dissuaded them from bolder maneuvers.

Ukraine’s restraint in Kherson now looks like a tactical decision. As Ukrainian Minister of Defense Oleksii Reznikov admitted Saturday, Ukraine’s generals had been planning to launch two campaigns simultaneously. If the Kherson offensive was designed to grind down Russian forces by drawing them in and then confronting them head-on, the Kharkiv Oblast offensive had greater territorial ambitions. Ukraine hoped to retake the city of Kupyansk. The Russians were using this road-and-rail hub to get supplies to Izium, a base for their operations in the Donbas.

In retrospect, both offensives were possible only because of a ghastly summer of attritional warfare in that region. Since April the Ukrainians have suffered horrifying losses in that region but have inflicted even larger ones on the enemy. So the Russian army has been trying to hold a large and geographically unwieldy slice of Ukraine even as its own numbers decline. Ukraine, which has been conscripting soldiers since Putin started this war, has amassed an army larger than the Russian invasion force. Russian officials, meanwhile, are terrified of upsetting their populace and have avoided conscription—to the point of deploying mercenaries and sourcing soldiers from prisons and mental hospitals. So when Putin took the Ukrainians’ bait in Kherson, a shrinking Russian army moved forces away from the area that Ukraine wanted to attack and toward an area where Ukraine was waging a war of attrition.

The Ukrainians wrote a script, and the Russians played their assigned role. Unlike Kherson, where the invaders had massed forces and set up a multilayered defense, Kharkiv Oblast was thinly protected by the Russian forces. The Ukrainians were thus easily able to break Russian lines, which seem to have been held by poorly motivated and trained forces, and streak deep behind them. To give their forces the best chance to succeed, the Ukrainians also seem to have built up a substantial, fast-moving strike force. Without allowing details of their preparations to leak out—Ukrainian sources have disclosed little if any information valuable to Russia—they seem to have constructed a number of specialized combat brigades with lighter, faster wheeled vehicles. This has allowed them a crucial mobility advantage over their enemy.

Though the war is far from over and Russia can find new ways to punish Ukraine, collapsing Russian forces have not only been pushed back; in abandoning their former headquarters in Izium, they also left behind large stores of equipment and ammunition that the Ukrainians can now use against them. Even if the Russians stabilize the line in the coming days, they will be in a far worse position than they were on September 1. Building on months of careful efforts to both prepare Ukrainian forces and waste Russian ones, Ukraine has achieved a strategic masterstroke that military scholars will study for decades to come.

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/ID53TOVNCRG2HEUZYRQVJGGJSY.jpg)

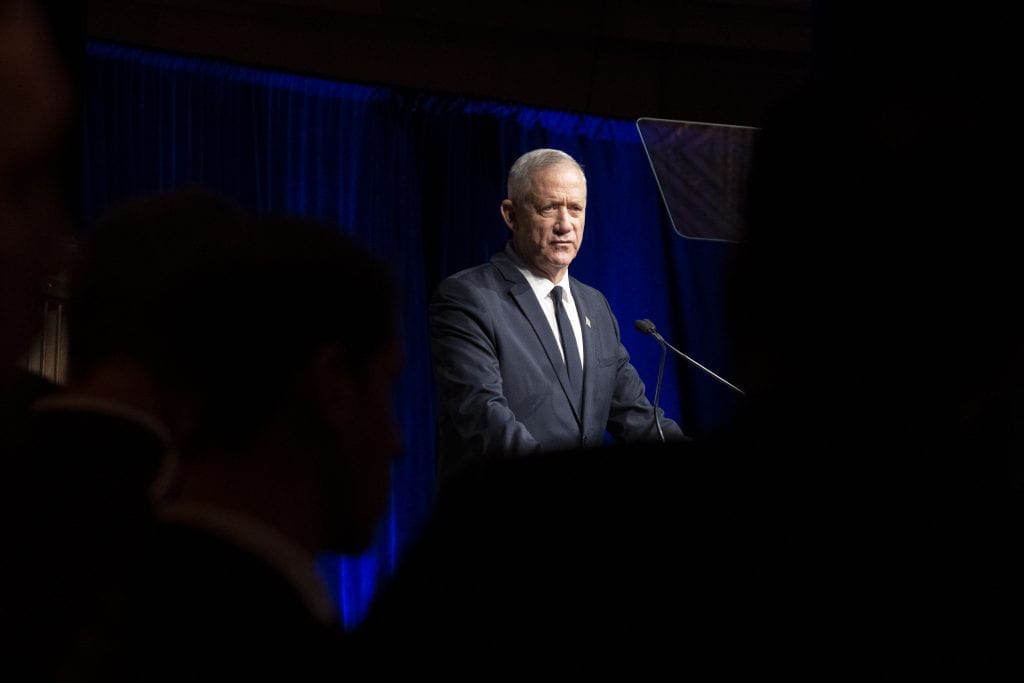

New US aid package: Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, and US secretary of state, Anthony Blinken, announce a US$2 billion aid package for Ukraine and Nato allies in eastern Europe. UPI/Alamy Stock Photo

New US aid package: Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, and US secretary of state, Anthony Blinken, announce a US$2 billion aid package for Ukraine and Nato allies in eastern Europe. UPI/Alamy Stock Photo