Gibbs McKinley

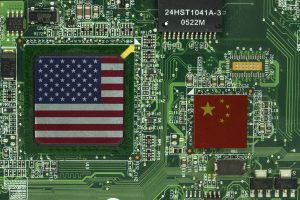

According to U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, when it comes to China, “We’ll just need one philosophy, with one principle, and America will be stronger for the future to come.” His statement followed a 365-65 vote by the U.S. House of Representatives to pass a resolution creating a special Select Committee on China, which will reassess U.S. policy on China. The bipartisan committee, and McCarthy’s statement, are emblematic of the now well-established consensus that China poses the greatest long-term threat to U.S. interests.

Washington often pines after such bipartisan agreement in foreign policy — that politics may stop at the water’s edge so Americans can face foreign threats united. It has found that unity in the growing shadow of the threat posed by China. But chasing consensus could lead decision-makers in Washington astray, with disastrous consequences. Bipartisan consensus, after all, tends to be right more frequently when it’s not the product of fear. Today, anxiety around China is as mounting as national awareness of the challenge China poses to U.S. interests rises — embodied in the public fervor around the Chinese spy balloon that floated across the country last month.

Policymakers should exercise caution when using the lens of political consensus to authorize a slew of transformative decisions and policies in response to China’s coercive or aggressive actions. Mutual validation is not a substitute for individual judgment, as history has shown. In fact, it can very easily lead to disastrous consequences. Two of the most controversial decisions in U.S. foreign policy – the 1964 Tonkin Gulf Resolution and the 2003 invasion of Iraq — gained incredible bipartisan consensus.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/J6SO5BA6AVBWZJD3JMDN6UM7NE.jpg)