David Vergun

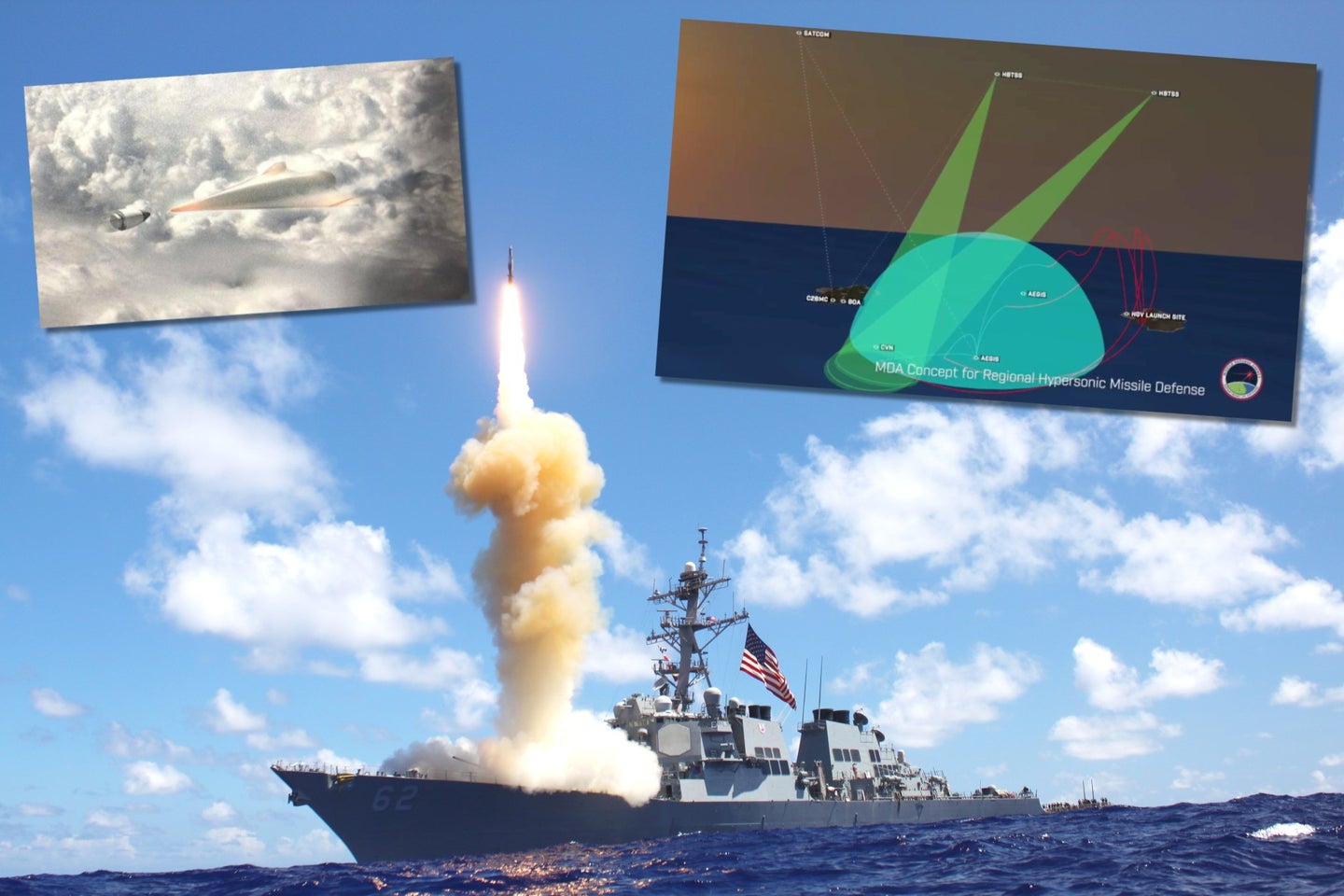

Missile defense plays a key role in U.S. national security. However, as missile technology matures and proliferates among potential adversaries China, Russia, North Korea and Iran, the threat to the U.S., deployed forces, allies and partners is increasing, the deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear and missile defense policy said.

Leonor Tomero provided testimony at a House Armed Services Subcommittee on Strategic Forces hearing regarding the fiscal year 2022 budget request for missile defense and missile defeat programs.

To address these evolving challenges, the Defense Department will review its missile defense policies, strategies and capabilities to ensure the U.S. has effective missile defenses, Tomero said.

The review will contribute to the department’s approach on integrated deterrence, she said, noting that the review is expected to be completed in January.

The department recently initiated development of the Next Generation Interceptor, she said, adding that the NGI will increase the reliability and capability of the United States’ missile defense.

T

T

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/ATZB5WRXOFGUPARMG6WI6QKYME.jpg)