Ingvild Bode and Hendrik Huelss

The use of force exercised by the militarily most advanced states in the last two decades has been dominated by ‘remote warfare’, which, at its simplest, is a ‘strategy of countering threats at a distance, without the deployment of large military forces’ (Oxford Research Group cited in Biegon and Watts 2019, 1). Although remote warfare comprises very different practices, academic research and the broader public pays much attention to drone warfare as a very visible form of this ‘new’ interventionism. In this regard, research has produced important insights into the various effects of drone warfare in ethical, legal, political, but also social and economic contexts (Cavallaro, Sonnenberg and Knuckey 2012; Sauer and Schörnig 2012; Casey-Maslen 2012; Gregory 2015; Hall and Coyne 2013; Schwarz 2016; Warren and Bode 2015; Gusterson 2016; Restrepo 2019; Walsh and Schulzke 2018). But current technological developments suggest an increasing, game-changing role of artificial intelligence (AI) in weapons systems, represented by the debate on emerging autonomous weapons systems (AWS). This development poses a new set of important questions for international relations, which pertain to the impact that increasingly autonomous features in weapons systems can have on human decision-making in warfare – leading to highly problematic ethical and legal consequences.

In contrast to remote-controlled platforms such as drones, this development refers to weapons systems that are AI-driven in their critical functions. That is weapons that process data from on-board sensors and algorithms to ‘select (i.e., search for or detect, identify, track, select) and attack (i.e., use force against, neutralise, damage or destroy) targets without human intervention’ (ICRC 2016). AI-driven features in weapons systems can take many different forms but clearly depart from what might be conventionally understood as ‘killer robots’ (Sparrow 2007). We argue that including AI in weapons systems is important not because we seek to highlight the looming emergence of fully autonomous machines making life and death decisions without any human intervention, but because human control is increasingly becoming compromised in human-machine interactions.

AI-driven autonomy has already become a new reality of warfare. We find it, for example, in aerial combat vehicles such as the British Taranis, in stationary sentries such as the South Korean SGR-A1, in aerial loitering munitions such as the Israeli Harop/Harpy, and in ground vehicles such as the Russian Uran-9 (see Boulanin and Verbruggen 2017). These diverse systems are captured by the (somewhat problematic) catch-all category of autonomous weapons, a term we use as a springboard to draw attention to present forms of human-machine relations and the role of AI in weapons systems short of full autonomy.

The increasing sophistication of weapons systems arguably exacerbates trends of technologically mediated forms of remote warfare that have been around for some decades. The decisive question is how new technological innovations in warfare impact human-machine interactions and increasingly compromise human control. The aim of our contribution is to investigate the significance of AWS in the context of remote warfare by discussing, first, their specific characteristics, particularly with regard to the essential aspect of distance and, second, their implications for ‘meaningful human control’ (MHC), a concept that has gained increasing importance in the political debate on AWS. We will consider MHC in more detail further below.

We argue thatAWS increase fundamental asymmetries in warfare and that they represent an extreme version of remote warfare in realising the potential absence of immediate human decision-making on lethal force. Furthermore, we examine the issue of MHC that has emerged as a core concern for states and other actors seeking to regulate AI-driven weapons systems. Here, we also contextualise the current debate with state practices of remote warfare relating to systems that have already set precedents in terms of ceding meaningful human control. We will argue that these incremental practices are likely to change use of force norms, which we loosely define as standards of appropriate action (see Bode and Huelss 2018). Our argument is therefore less about highlighting the novelty of autonomy, and more about how practices of warfare that compromise human control become accepted.

Autonomous Weapons Systems and Asymmetries in Warfare

AWS increase fundamental asymmetries in warfare by creating physical, emotional and cognitivedistancing. First, AWS increase asymmetry by creating physical distance in completely shielding their commanders/operators from physical threats or from being on the receiving end of any defensive attempts. We do not argue that the physical distancing of combatants has started with AI-driven weapons systems. This desire has historically been a common feature of warfare – and every military force has an obligation to protect its forces from harm as much as possible,which some also present as an argument for remotely-controlled weapons (see Strawser 2010). Creating an asymmetrical situation where the enemy combatant is at the risk of injury while your own forces remain safe is, after all, a basic desire and objective of warfare.

But the technological asymmetry associated with AI-driven weapon systems completely disturbs the ‘moral symmetry of mortal hazard’ (Fleischman 2015, 300) in combat and therefore the internal morality of warfare. In this type of ‘riskless warfare, […] the pursuit of asymmetry undermines reciprocity’ (Kahn 2002, 2). Following Kahn (2002, 4), the internal morality of warfare largely rests on ‘self-defence within conditions of reciprocal imposition of risk.’ Combatants are allowed to injure and kill each other ‘just as long as they stand in a relationship of mutual risk’ (Kahn 2002, 3). If the morality of the battlefield relies on these logics of self-defence, this is deeply challenged by various forms of technologically mediated asymmetrical warfare. It has been voiced as a significant concern in particular since NATO’s Kosovo campaign (Der Derian 2009) and has since grown more pronounced through the use of drones and, in particular, AI-driven weapons systems that decrease the influence of humans on the immediate decision-making of using force.

Second, AWS increase asymmetry by creating an emotional distance from the brutal reality of wars for those who are employing them. While the intense surveillance of targets and close-range experience of target engagement through live pictures can create intimacy between operator and target, this experience is different from living through combat. At the same time, the practice of killing from a distance triggers a sense of deep injustice and helplessness among those populations affected by the increasingly autonomous use of force who are ‘living under drones’ (Cavallaro, Sonnenberg and Knuckey 2012). Scholars have convincingly argued that ‘the asymmetrical capacities of Western – and particularly US forces – themselves create the conditions for increasing use of terrorism’ (Kahn 2002, 6), thus ‘protracting the conflict rather than bringing it to a swifter and less bloody end’ (Sauer and Schörnig 2012, 373; see also Kilcullen and McDonald Exum 2009; Oudes and Zwijnenburg 2011).

This distancing from the brutal reality of war makes AWS appealing to casualty-averse, technologically advanced states such as the USA, but potentially alters the nature of warfare. This also connects well with other ‘risk transfer paths’ (Sauer and Schörnig 2012, 369) associated with practices of remote warfare that may be chosen to avert casualties, such as the use of private military security companies or working via airpower and local allies on the ground (Biegon and Watts 2017). Casualty aversion has been mostly associated with a democratic, largely Western, ‘post-heroic’ way of war depending on public opinion and the acceptance of using force (Scheipers and Greiner 2014; Kaempf 2018). But reports about the Russian aerial support campaign in Syria, for example, speak of similar tendencies of not seeking to put their own soldiers at risk (The Associated Press 2018). Mandel (2004) has analysed this casualty aversion trend in security strategy as the ‘quest for bloodless war’ but, at the same time, noted that warfare still and always includes the loss of lives – and that the availability of new and ever more advanced technologies should not cloud thinking about this stark reality.

Some states are acutely aware of this reality as the ongoing debate on the issue of AWS at the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (UN-CCW) demonstrates. It is worth noting that most countries in favour of banning autonomous weapons are developing countries, which are typically less likely to attend international disarmament talks (Bode 2019). The fact that they are willing to speak out strongly against AWS makes their doing so even more significant. Their history of experiencing interventions and invasions from richer, more powerful countries (such as some of the ones in favour of AWS) also reminds us that they are most at risk from this technology.

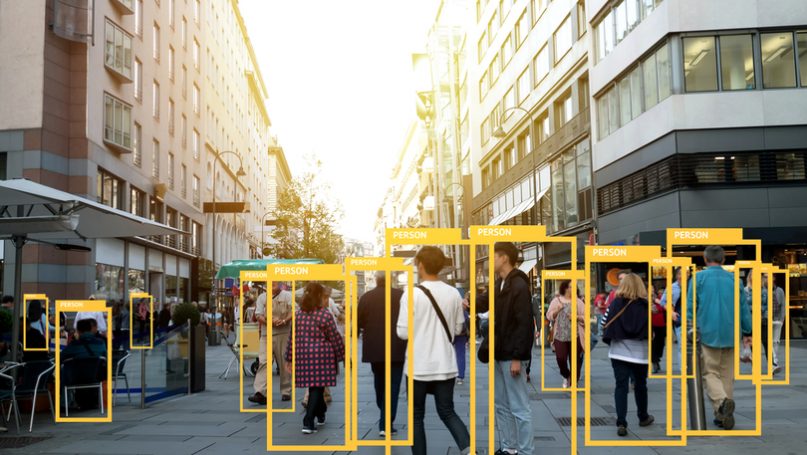

Third, AWS increase cognitive distance by compromising the human ability to ‘doubt algorithms’ (see Amoore 2019) in terms of data outputs at the heart of the targeting process. As humans using AI-driven systems encounter a lack of alternative information allowing them to substantively contest data output, it is increasingly difficult for human operators to doubt what ‘black box’ machines tell them. Their superior data processing capacity is exactly why target identification via pattern recognition in vast amounts of data is ‘delegated’ to AI-driven machines, using, for example, machine-learning algorithms at different stages of the targeting process and in surveillance more broadly.

But the more target acquisition and potential attacks are based on AI-driven systems as technology advances, the less we seem to know about how those decisions are made. To identify potential targets, countries such as the USA (e.g. SKYNET programme) already rely on meta-data generated by machine-learning solutions focusing on pattern of life recognition (The Intercept 2015; see also Aradau and Blanke 2018). However, the lacking ability of humans to retrace how algorithms make decisions poses a serious ethical, legal and political problem. The inexplicability of algorithms makes it harder for any human operator, even if provided a ‘veto’ or the power to intervene ‘on the loop’ of the weapons system, to question metadata as the basis of targeting and engagement decisions. Notwithstanding these issues, as former Assistant Secretary for Homeland Security Policy Stewart Baker put it, ‘metadata absolutely tells you everything about somebody’s life. If you have enough metadata, you don’t really need content’, while General Michael Hayden, former director of the NSA and the CIA emphasises that ‘[w]e kill people based on metadata’ (both quoted in Cole 2014).

The desire to find (quick) technological fixes or solutions for the ‘problem of warfare’ has long been at the heart of debates on AWS. We have increasingly seen this at the Group of Governmental Experts on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (GGE) meetings at the UN-CCW in Geneva when countries already developing such weapons highlight their supposed benefits. Those in favour of AWS (including the USA, Australia and South Korea) have become more vocal than ever. The USA claimed that such weapons could actually make it easier to follow international humanitarian law by making military action more precise (United States 2018). But this is a purely speculative argument at present, especially in complex, fast-changing contexts such as urban warfare. Key principles of international humanitarian law require deliberate human judgements that machines are incapable of (Asaro 2018; Sharkey 2008). For example, the legal definition of who is a civilian and who is a combatant is not written in a way that could be easily programmed into AI, and machines lack the situational awareness and ability to infer things necessary to make this decision (Sharkey 2010).

Yet, some states seem to pretend that these intricate and complex issues are easily solvable through programming AI-driven weapons systems in just the right way. This feeds the technological ‘solutionism’ (Morozov 2014) narrative that does not appear to accept that some problems do not have technological solutions because they are inherently political in nature. So, quite apart from whether it is technologically possible, do we want, normatively, to take out deliberate human decision-making in this way?

This brings us to our second set of arguments concerned with the fundamental questions that introducing AWS into practices of remote warfare pose to human-machine interaction.

The Problem of Meaningful Human Control

AI-driven systems signal the potential absence of immediate human decision-making on lethal force and the increasing loss of so-called meaningful human control (MHC). The concept of MHC has become a central focus of the ongoing transnational debate at the UN-CCW. Originally coined by the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Article 36 (Article 36 2013, 36; see Roff and Moyes 2016), there are different understandings of what meaningful human control implies (Ekelhof 2019). It promises resolving the difficulties encountered when attempting to define precisely what autonomy in weapons systems is but also meets somewhat similar problems in its definition of key concepts. Roff and Moyes (2016, 2–3) suggest several factors that can enhance human control over technology: technology is supposed to be predictable, reliable, transparent; users should have accurate information; there is timely human action and a capacity for timely intervention, as well as human accountability. These factors underline the complex demands that could be important for maintaining MHC but how these factors are linked and what degree of predictability or reliability, for example, are necessary to make human control meaningful remains unclear and these elements are underdefined.

In this regard, many states consider the application of violent force without any human control as unacceptable and morally reprehensible. But there is less agreement about various complex forms of human-machine interaction and at what point(s) human control ceases to be meaningful. Should humans always be involved in authorising actions or is monitoring such actions with the option to veto and abort sufficient? Is meaningful human control realised by engineering weapons systems and AI in certain ways? Or, more fundamentally, is human control that consists of simply executing decisions based on indications from a computer that are not accessible to human reasoning due to the ‘black-boxed’ nature of algorithmic processing meaningful? The noteworthy point about MHC as a norm in the context of AWS is also that it has long been compromised in different battlefield contexts. Complex human-machine interactions are not a recent phenomenon – even the extent to which human control in a fighter jet is meaningful is questionable (Ekelhof 2019).

However, the attempts to establish MHC as an emerging norm meant to regulate AWS are difficult. Indeed, over the past four years of debate in the UN-CCW, some states, supported by civil society organisations, have advocated introducing new legal norms to prohibit fully autonomous weapons systems, while other states leave the field open in order to increase their room of manoeuvre. As discussions drag on with little substantial progress, the operational trend towards developing AI-enabled weapons systems continues and is on track to becoming established as ‘the new normal’ in warfare (P. W. Singer 2010). For example, in its Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap 2013–2038, the US Department of Defence sets out a concrete plan to develop and deploy weapons with ever increasing autonomous features in the air, on land, and at sea in the next 20 years (US Department of Defense 2013).

While the US strategy on autonomy is the most advanced, a majority of the top ten arms exporters, including China and Russia, are developing or planning to develop some form of AI-driven weapon systems. Media reports have repeatedly pointed to the successful inclusion of machine learning techniques in weapons systems developed by Russian arms maker Kalashnikov, coming alongside President Putin’s much-publicised quote that ‘whoever leads in AI will rule the world’ (Busby 2018; Vincent 2017). China has reportedly made advances in developing autonomous ground vehicles (Lin and Singer 2014) and, in 2017, published an ambitiously worded government-led plan on AI with decisively increased financial expenditure (Metz 2018; Kania 2018).

The intention to regulate the practice of using force by setting norms stalls at the UN-CCW, but we highlight the importance of a reverse and likely scenario: practices shaping norms. These dynamics point to a potentially influential trajectory AWS may take towards changing what is appropriate when it comes to the use of force, thereby also transforming international norms governing the use of violent force.

We have already seen how the availability of drones has led to changes in how states consider using force. Here, access to drone technology appears to have made targeted killing seem an acceptable use of force for some states, thereby deviating significantly from previous understandings (Haas and Fischer 2017; Bode 2017; Warren and Bode 2014). In their usage of drone technology, states have therefore explicitly or implicitly pushed novel interpretations of key standards of international law governing the use of force, such as attribution and imminence. These practices cannot be captured with the traditional conceptual language of customary international law if they are not openly discussed or simply do not amount to its tight requirements, such as becoming ‘uniform and wide-spread’ in state practice or manifesting in a consistently stated belief in the applicability of a particular rule. But these practices are significant as they have arguably led to the emergence of a series of grey areas in international law in terms of shared understandings of international law governing the use of force (Bhuta et al. 2016). The resulting lack of clarity leads to a more permissive environment for using force: justifications for its use can more ‘easily’ be found within these increasingly elastic areas of international law.

We therefore argue that we can study how international norms regarding using AI-driven weapons systems emerge and change from the bottom-up, via deliberative and non-deliberative practices. Deliberative practices as ways of doing things can be the outcome of reflection, consideration or negotiation. Non-deliberative practices, in contrast, refer to operational and typically non-verbalised practices undertaken in the process of developing, testing and deploying autonomous technologies.

We are currently witnessing, as described above, an effort to potentially make new norms regarding AI-driven weapons technologies at the UN-CCW via deliberative practices. But at the same time, non-deliberative and non-verbalised practices are constantly undertaken as well and simultaneously shape new understandings of appropriateness. These non-deliberative practices may stand in contrast to the deliberative practices centred on attempting to formulate a (consensus) norm of meaningful human control.

This does not only have repercussions for systems currently in different stages of development and testing, but also for systems with limited AI-driven capabilities that have been in use for the past two to three decades such as cruise missiles and air defence systems. Most air defence systems already have significant autonomy in the targeting process and military aircrafts have highly automatised features (Boulanin and Verbruggen 2017). Arguably, non-deliberative practices surrounding these systems have already created an understanding of what meaningful human control is. There is, then, already a norm, in the sense of an emerging understanding of appropriateness, emanating from these practices that has not been verbally enacted or reflected on. This makes it harder to deliberatively create a new meaningful human control norm.

Friendly fire incidents involving the US Patriot system can serve as an example here. In 2003, a Patriot battery stationed in Iraq downed a British Royal Airforce Tornado that had been mistakenly identified as an Iraqi anti-radiation missile. Notably, ‘[t]he Patriot system is nearly autonomous, with only the final launch decision requiring human interaction’ (Missile Defense Project 2018). The 2003 incident demonstrates the extent to which even a relatively simple weapons system – comprising of elements such as radar and a number of automated functions meant to assist human operators – deeply compromises an understanding of MHC where a human operator has all required information to make an independent, informed decision that might contradict technologically generated data.

While humans were clearly ‘in the loop’ of the Patriot system, they lacked the required information to doubt the system’s information competently and were therefore mislead: ‘[a]ccording to a summary of a report issued by a Pentagon advisory panel, Patriot missile systems used during battle in Iraq were given too much autonomy, which likely played a role in the accidental downings of friendly aircraft’ (Singer 2005). This example should be seen in the context of other, well-known incidents such as the 1988 downing of Iran Air flight 655 due to a fatal failure of the human-machine interaction of the Aegis system on board the USS Vincennes or the crucial intervention of Stanislav Petrov who rightly doubted information provided by the Soviet missile defence system reporting a nuclear weapons attack (Aksenov 2013). A 2016 incident in Nagorno-Karabakh provides another example of a system with autonomous anti-radar mode used in combat: Azerbaijan reportedly used an Israeli-made Harop ‘suicide drone’ to attack a bus of allegedly Armenian military volunteers, killing seven (Gibbons-Neff 2016). The Harop is a loitering munition able to launch autonomous attacks.

Overall, these examples point to the importance of targeting for considering the autonomy in weapons systems. There are currently at least 154 weapons systems in use where the targeting process, comprising ‘identification, tracking, prioritisation and selection of targets to, in some cases, target engagement’ is supported by autonomous features (Boulanin and Verbruggen 2017, 23). The problem we emphasise here pertains not to the completion of the targeting cycle without any human intervention, but already emerges in the support functionality of autonomous features. Historical and more recent examples show that, here, human control is already often far from what we would consider as meaningful. It is noted, for example, that ‘[t]he S-400 Triumf, a Russian-made air defence system, can reportedly track more than 300 targets and engage with more than 36 targets simultaneously’ (Boulanin and Verbruggen 2017, 37). Is it possible for a human operator to meaningfully supervise the operation of such systems?

Yet, the apparent lack/compromised form of human control is apparently considered as acceptable: neither the use of the Patriot system has been questioned in relation to fatal incidents nor is the S-400 contested for featuring an ‘unacceptable’ form of compromised human control. In this sense, the wider-spread usage of such air defence systems over decades has already led to new understandings of ‘acceptable’ MHC and human-machine interaction, triggering the emergence of new norms.

However, questions about the nature and quality of human control raised by these existing systems are not part of the ongoing discussion on AWS among states at the UN-CCW. In fact, states using automated weapons continue to actively exclude them from the debate by referring to them as ‘semi-autonomous’ or so-called ‘legacy systems.’ This omission prevents the international community from taking a closer look at whether practices of using these systems are fundamentally appropriate.

Conclusion

To conclude, we would like to come back to the key question inspiring our contribution: to what extent will AI-driven weapons systems shape and transform international norms governing the use of (violent) force?

In addressing this question, we should also remember who has agency in this process. Governments can (and should) decide how they want to guide this process rather than presenting a particular trajectory of the process as inevitable or framing technological progress of a certain kind as inevitable. This requires an explicit conversation about the values, ethics, principles and choices that should limit and guide the development, role and the prohibition of certain types of AI-driven security technologies in light of standards for appropriate human-machine interaction.

Technologies have always shaped and altered warfare and therefore how force is used and perceived (Ben-Yehuda 2013; Farrell 2005). Yet, the role that technology plays should not be conceived in deterministic terms. Rather, technology is ambivalent, making how it is used in international relations and in warfare a political question. We want to highlight here the ‘Collingridge dilemma of control’ (see Genus and Stirling 2018) that speaks of a common trade-off between knowing the impact of a given technology and the ease of influencing its social, political, and innovation trajectories. Collingridge (1980, 19) stated the following:

Attempting to control a technology is difficult […] because during its early stages, when it can be controlled, not enough can be known about its harmful social consequences to warrant controlling its development; but by the time these consequences are apparent, control has become costly and slow.

This describes the situation aptly that we find ourselves in regarding AI-driven weapon technologies. We are still at an initial, development stage of these technologies. Not many systems are in operation that have significant AI-capacities. This makes it potentially harder to assess what the precise consequences of their use in remote warfare will be.The multi-billion investments made in various military applications of AI by, for example, the USA does suggest the increasing importance and crucial future role of AI. In this context, human control is decreasing and the next generation of drones at the core of remote warfare as the practice of distance combat will incorporate more autonomous features. If technological developments proceed at this pace and the international community fails to prohibit or even regulate autonomy in weapons systems, AWS are likely to play a major role in the remote warfare of the nearer future.

At the same time, we are still very much in the stage of technological development where guidance is possible, less expensive, less difficult, and less time-consuming – which is precisely why it is so important to have these wider, critical conversations about the consequences AI for warfare now.

No comments:

Post a Comment