Rebecca Banagala

With the announcement that Defence Space Command operations have kicked off, it’s unsurprising that Australia’s defence and national security experts are increasingly talking about space.

In March, then defence minister and now opposition leader Peter Dutton said he was eager to avoid space becoming a threat environment that either breeds conflict or exacerbates tensions back on earth. He described space as becoming increasingly congested and contested and announced that Australia will ‘invest in new military space capabilities to counter threats … to uphold the free use of space’.

That’s why we’ve seen trials by companies such as the Boeing’s test flight of the Starliner to the International Space Station, and budget commitments in abundance. Funding was allocated for building space command’s kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities, enhancing Australian space capability and locally made satellites, and expanding the international space investment with India. Things appear to be looking up for those who’ve long campaigned for a greater focus on security threats emanating from (or in) space.

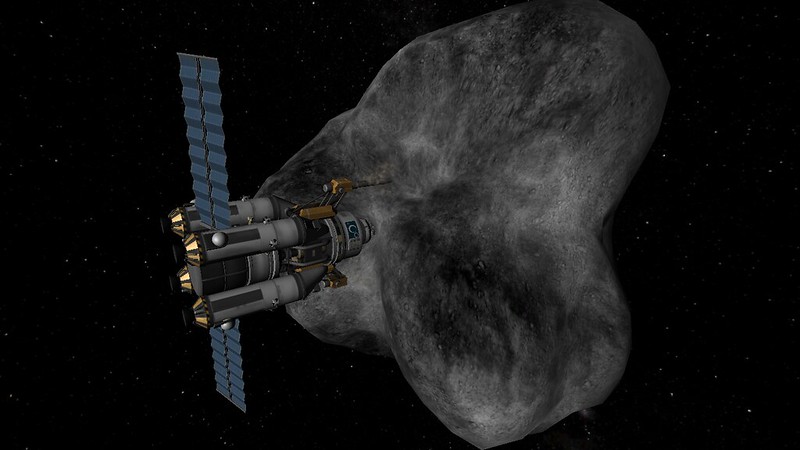

Geopolitical and regional competition has been extending to space, and this competition has leaked into the pursuit of commercial mining in space. And while space mining for critical minerals sounds like something out of a science fiction novel, it’s not a new idea at all. The extraction of resources from asteroids, the moon and other planets is very much a real thing, and there’s a lot of money behind it. In fact, it’s an issue of increasing strategic and critical importance, and has been spoken about for more than a decade.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty—signed by the US, Russia and other space-faring nations—doesn’t prohibit private companies from mining celestial resources, so commercial space mining is technically legal. Space mining operations will see the deployment of innovative new technologies, including advanced robotics and automated systems (such as Planetary Resources’ Arkyd-6), that will open up a whole world of new opportunities and technological breakthroughs.

The World Economic Forum also says that space mining can support the transition to a net-zero carbon economy. With the election outcome demonstrating that climate change is of growing importance to everyday Australians, the demand for electric vehicles and charging infrastructure is expected to grow strongly. Energy-storage technology, as well as projects in renewables, will require increased innovation to develop batteries that are more reliable. Lithium-ion batteries deliver power on a short-term basis, but long-duration power delivery is required to meet consumer demands on earth, both now and into the future.

However, critical minerals for batteries are becoming increasingly difficult to source. Global supply-chain interruptions over the past few years have caused avoidable hindrances to accessing metals such as cobalt, nickel, lithium, copper and other rare-earth elements. The result is a two-pronged economic and national security nightmare, and ultimately a failure to meet consumer demands.

Geologists believe that asteroids are packed with these precious metals and much more, in quantities that exceed the earth’s reserves. The market for asteroid mining is valued in the trillions, and can help support and propel forward-learning climate practices in Australia. It’s truly an opportunity that’s revolutionary, and could help give us the answer to many questions. And it isn’t just private companies that can reap these celestial benefits.

In 2015, the US Congress signed a bill to enable American citizens to own mined resources from space, and in 2020, former president Donald Trump signed an order encouraging them to mine space for commercial purposes. The US is making space its new stomping ground—but so are other countries. India and China have both publicly signalled their intentions to extract helium-3 from the moon.

Yet for all its potential benefits, not everybody is a fan of space mining. For its part, Roscosmos, Russia’s space agency, likened space mining to colonialism. Others have raised ethical considerations and legal concerns.

The lack of regulation around space activities opens the door to amendments to the 1967 treaty. NASA in 2020 proposed a legal framework for space-faring nations called the Artemis Accords, aiming to design a set of principles for activities by space-faring nations. But new agreements to facilitate private investment, provide clarity on obligations for state and commercial activities, and ensure international cooperation is maintained will be vital.

Revisions to the treaty must be made soon, because before we know it, space will be the new frontier that breeds conflict and hostility in our geopolitical and geostrategic environment. To get ahead of that curve, we’ll need some revolutionary thinking that is truly out of this world.

No comments:

Post a Comment