By Christopher K. Colley

The Chinese naval parade in Qingdao on April 23, celebrating the 70th anniversary of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), showcased multiple indigenously produced Chinese warships and submarines. Most prominent of these were an upgraded Type 094 Jin-class nuclear powered ballistic missile submarine and the new 10,000-13,000 ton Type 055 guided missile destroyer. This event is the latest example of China flexing its maritime muscles and demonstrating to the region, and the world, that the PLAN is quickly developing into a powerful force.

The Chinese naval parade in Qingdao on April 23, celebrating the 70th anniversary of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), showcased multiple indigenously produced Chinese warships and submarines. Most prominent of these were an upgraded Type 094 Jin-class nuclear powered ballistic missile submarine and the new 10,000-13,000 ton Type 055 guided missile destroyer. This event is the latest example of China flexing its maritime muscles and demonstrating to the region, and the world, that the PLAN is quickly developing into a powerful force.

A key question is whether this growth been matched with the emergence of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as a major bureaucratic force within the Chinese government. Does the PLA have the ability to significantly influence the decision-making process on events related to foreign and security affairs?

Possible evidence in support of this can be found in increasing PLA budgets, which this year rose by 7.5 percent, and a steady output of modern military equipment and naval platforms and submarines. While the PLA budget increase this year is slightly down compared to previous years, the budget has expanded rapidly since the start of this century. Specific budget allocations to various services in the Chinese military are not publicly available, but according to experts on Chinese security interviewed in China and the United States, the PLAN is believed to occupy between 25-30 percent of the overall Chinese military budget. Importantly, the expanding role and responsibilities of the PLAN (with former Chinese leader Hu Jintao calling for China to become a “great maritime power”) suggests increasing influence and clout in Chinese foreign and security policy.

Even though the PLA and PLAN have greatly increased their responsibilities and budgets, an examination of their representation in the formal channels of Chinese power casts substantial doubt on their influence in the game of bureaucratic politics and decision-making in Beijing.

A Declining Role

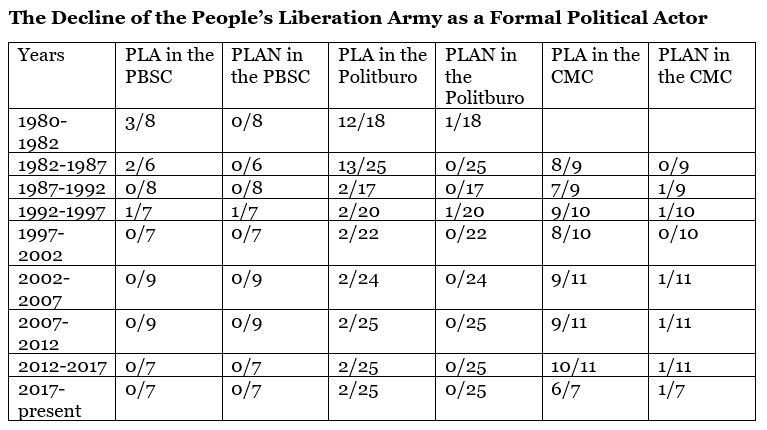

Since 1980, the PLA and, specifically, the PLAN, have seen their representation in Chinese formal institutions of power decline significantly. An analysis of the most powerful decision-making body in China, the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC), reveals that the PLA (and thus the PLAN) have been locked out of this committee since 1997, when Admiral Liu Huaqing was the last representative. China’s second most powerful formal political institution, the Politburo, has had only two Chinese military representatives since 1987, and the PLAN has not had a single representative on this body since 1997. As demonstrated in the chart below, military representation in general has declined enormously since the early 1980s, when the PLA constituted between two-thirds and one-half of the entire Politburo from 1980-1987. In fact from 1980-1982 (the 11th Party Congress) and 1982-1987 (the 12th Party Congress) the PLA constituted one-third or more of the PBSC.

(Author’s data set derived from multiple Chinese government sources)

The absence of the PLA from the PBSC, at least officially, leaves the PLA out of the most important decision-making entity. One more measure of the PLA’s declining influence is found in its absence from the Secretariatsince 2007. The Secretariat is the most important body for implementing the decisions of the PBSC and PB. It is composed of high-level state and Communist Party leaders.

Another important finding is that, at least as far as formal political institutions are concerned, since 1982, the PLAN has never garnered more than one seat on the Central Military Commission (CMC). Even as its responsibilities have multiplied over the past two decades, its representation has been less than 10 percent for most of this period and, as of 2019, the PLAN only occupies one of seven seats on the CMC (Admiral Miao Hua). Likewise, the PLAN has not had any representatives in the Politburo since 1997.

The inability of the PLA to withstand the anti-corruption purges of Xi Jinping is further evidence of its limited influence. Since reforms in the PLA were announced in 2015, more than 100 senior PLA officers have been charged with corruption and Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong, both previous vice chairmen of the CMC, were taken down in the anti-corruption campaigns.

It is possible that the PLA and PLAN are influencing policy through informal channels based on personal connections with China’s top leaders. However, this is very difficult to ascertain as there is limited evidence. In the past, PLAN leaders, including Liu Huaqing, were rebuffed by Chinese leaders in their attempts to procure various weapons systems, including aircraft carriers in the 1990s. Interviews with Chinese security scholars indicate that the PLA is firmly under the control of the CCP and does not deviate from civilian control. While informal politics play a significant role in China, if the PLA were able to utilize its informal network, one would expect to see it gain greater representation on the formal decision-making bodies as well as insulating itself from the anti-corruption purges.

Conclusion

Despite being relegated to the fringes of power, the PLA and, especially, the PLAN have seen their budgets and overseas activities increase enormously over the past two decades. However, while their warfighting capabilities have greatly expanded, their roles in the formal channels of power in China have been substantially reduced. This may have significant implications for defense policy as well as for China’s foreign relations. A PLA that is more focused on China’s national defense, and less on politics, will likely be a more professional military.

In the years ahead the PLAN will take on a greater and more visible role in China’s foreign affairs, especially in the Indian Ocean Region where six to eight Chinese warships are deployed at any given time. But likely future naval bases in the Indian Ocean Region, in addition to the current one in Djibouti, will be better viewed as the result of decisions made by Chinese civilian leaders, as opposed to a nationalistic PLA/PLAN forcing its agenda for a more assertive China. Finally, it is important for policy analysts not to overestimate the role of the PLA in China’s foreign policy. Perceptions (real or imagined) of an increasingly assertive China, may be the result of Chinese leaders flexing their newfound power, as opposed to a clique of military leaders pursuing their own narrow PLA centric policies.

Christopher K. Colley is Assistant Professor of Security Studies at the National Defense College of the United Arab Emirates. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the National Defense College, or the United Arab Emirates government.

No comments:

Post a Comment