When we began drafting this study of U.S. military spending and force posture, we had no way of knowing the tremendous challenge that COVID-19 would pose. It has wreaked havoc on the economy. It has disrupted every facet of American life. The impact will reverberate for generations. The global pandemic—and the U.S. government’s response to it—has threatened the lives and liberties of Americans as well as the United States’ standing in the world.

When we began drafting this study of U.S. military spending and force posture, we had no way of knowing the tremendous challenge that COVID-19 would pose. It has wreaked havoc on the economy. It has disrupted every facet of American life. The impact will reverberate for generations. The global pandemic—and the U.S. government’s response to it—has threatened the lives and liberties of Americans as well as the United States’ standing in the world.

This disaster is a call to action. The threat posed by nontraditional security challenges, including pandemics, climate change, and malicious disinformation, should prompt a thoroughgoing reexamination of the strategies, tactics, and tools needed to keep the United States safe and prosperous.

As of this writing in late April 2020, and well before the full impact of COVID-19 is known, it seems obvious to us that the United States can no longer justify spending massive amounts of money on quickly outdated and vulnerable weapons systems, equipment that is mostly geared to fight an enemy that might never materialize. Meanwhile, the clearest threats to public safety and political stability in the United States are very much evident and all around us. Just how demonstrations of force or foreign stability operations contribute to U.S. national security is particularly questionable at a time when a microscopic enemy has brought the entire world to a standstill.

This analysis mostly examines where the U.S. military was as of December 31, 2019, with a few observations from early 2020. Where it will be on December 31, 2020, will be guided by a critical set of questions. The authors, and the entire team of scholars in the Cato Institute’s Defense and Foreign Policy Studies Department, intend to help frame those questions—and to answer as many as possible—over the coming year.

Security politics will be different in the future, but the goal of security policy hasn’t changed and is clearly outlined in this report: to identify the most effective and efficient means for advancing Americans’ safety and prosperity. That entails ending the forever wars, terminating needless military spending, rethinking the fundamentals of strategic deterrence, and focusing the entire defense establishment on innovation and adaptation.

Even before COVID-19, military spending was unsustainable. In a new Cato report, scholars argue that nontraditional security challenges require a thorough reexamination of national defense strategy. The report prioritizes ending the forever wars, terminating needless military spending, rethinking the fundamentals of strategic deterrence, and focusing the entire defense establishment on innovation and adaptation.

Executive Summary

Budgetary and strategic inertia has impeded the development of a U.S. military best suited to deal with future challenges. Over the past several decades, the military has repeatedly answered the call to arms as American foreign policy privileges the use of force over other instruments of power and influence. The era of near endless war has now stretched into its third decade. Going forward, Washington should realign national security objectives and motivate allies and partners to become more capable as America’s relative military advantage wanes and the focus inevitably turns to domestic priorities, including public health.

As policymakers transition from primacy and unilateral military dominance, and beyond the post‐9/11 wars in the greater Middle East, the force must also be reoriented. The defense establishment’s most urgent requirement is prioritization. The nation’s resource constraints are real, and hard choices cannot be postponed. In particular, all military branches should emphasize innovation over the preservation of legacy systems and practices. This will require cooperation from Congress, which must address the budget pathologies that stifle new thinking and keep the Pentagon locked into old ways of doing business. Senior defense officials must orient the future force around a different approach to power projection, one less dependent on permanent forward bases, and toward a renewed focus on the requirements for strategic deterrence. The services must also think anew about how to best capture and use information.

Despite recent challenges and setbacks, most importantly the COVID-19 outbreak and response, the United States still enjoys many advantages, including a dynamic economy, political stability, and favorable geography. Securing the United States from future threats should sustain and build on those advantages. Restraining the impulse to use force, imposing limits on military spending, and relying more heavily on diplomacy, trade, and cultural exchange would relieve the burdens on our overstressed military. The ultimate objective should be to build an agile and adaptable military that can address a range of future challenges but is used more judiciously in the service of vital U.S. interests and to deter attacks against the homeland.

Introduction

Building a modern military requires a clear conceptualization of the realities of international conflict and tight alignment with a country’s foreign policy. Strategic planners must have a clear‐eyed view of both the threats facing the country and the tools necessary to defend its vital interests. Planners in the United States should take account of the country’s fortunate circumstances, including its geography, dynamic economy, and political stability, and recognize that maintaining these advantages does not require a massive military apparatus that is constantly active in nearly every part of the world.

For decades, however, U.S. national security policy has been oriented around a military‐centric approach, variously called primacy, liberal hegemony, or deep engagement. Primacy is based on the idea that U.S. military power explains the absence of a major‐power war since the end of World War II and the attendant rise in productivity and living standards. Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington predicted in 1993, for example, that “a world without U.S. primacy will be a world with more violence and disorder and less democracy and economic growth.”1 Former secretary of state George Shultz put it even more succinctly in the 2016 documentary American Umpire: “If the United States steps back from the historic role [it has] played since World War II, the world will come apart at the seams.”2

Such sentiments reflect why, despite the fact that the United States enjoys relative safety, U.S. officials see only grave and urgent dangers. They see any challenge to U.S. military dominance as a threat to global liberty and peace. The 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), for example, notes that the “central challenge to U.S. prosperity and security is the reemergence of long‐term, strategic competition by … revisionist powers.” The goal then, according to the NDS, is to “remain the preeminent military power in the world.”3 The 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS) goes further, noting that the “United States must retain overmatch—the combination of capabilities in sufficient scale to prevent enemy success and to ensure America’s sons and daughters will never be in a fair fight.”4

And while the United States is purportedly orienting around great power competition against China and Russia, the post‐9/11 conflicts grind on. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2020 makes clear that the Pentagon envisions those conflicts continuing indefinitely.5 Today’s U.S. military budget, after adjusting for inflation, vastly exceeds that of the Cold War and now approaches levels during the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 2010s (see Figure 1). Operationally, the Pentagon has been bogged down in Afghanistan and caught in the ongoing struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran for dominance in the Persian Gulf region and beyond; in December 2019, the Trump administration was considering sending an additional 14,000 troops to the Middle East, including a substantial ground presence in Saudi Arabia, for the first time in nearly 17 years.6

Perceptions of looming threats or fear of potential peer competitors should not distract from the obvious need to take a strategic pause and reconsider the United States’ core defensive needs, especially during a global pandemic and associated economic disaster.7 Washington should realign its national security ends and means to better match the emerging geopolitical reality—especially America’s waning relative military power.8 The desire for one‐sided “overmatch” is understandable but impractical given the extensive commitments it entails. The time is ripe to make a clean break from the past.

The dramatic shock of COVID-19 adds urgency to the need for new strategic priorities. This report acknowledges that the nation’s resource constraints are real and that the United States faces a period of grave economic uncertainty. The Pentagon is not immune to these pressures. Politicians are unlikely to undertake a concerted campaign to build public support for massive increases in taxes or deep cuts to popular domestic programs in order to fund a military that an ambitious grand strategy calls for, and they would likely fail if they tried. The U.S. military is spending beyond its means due mostly to inertia and strategic indecision. To that end, this report is founded on three pillars: articulating a force that meets the realities of the geopolitical situation and contemplating the current budget pathologies that impede change; reexamining force construction; and evaluating the posture needed for modern strategic deterrence. These pillars drive the recommendations contained herein with an aim toward developing a more realistic and prudent military budget.

A Restraint‐Focused Strategy

The Trump administration’s budget proposal for fiscal year (FY) 2021 aims for “U.S. military dominance in all warfighting domains—air, land, seas, space, and cyberspace,” echoing its FY 20 budget proposal, which supported “dominance across all domains.”9 This view is consistent with the desire for “overmatch” in the NSS. Overmatch requires the United States to “restore our ability to produce innovative capabilities, restore the readiness of our forces for major war, and grow the size of the force so that it is capable of operating at a sufficient scale and for ample duration to win across a range of scenarios.”10

This quest for global dominance is taking place as the United States’ capacity for sustaining supremacy is waning. The NDS observes, for example, that “we are emerging from a period of strategic atrophy, aware that our competitive military advantage has been eroding. We are facing increasing global disorder, characterized by decline in the long‐standing rules‐based international order—creating a security environment more complex and volatile than any we have experienced in recent memory.”11

The NDS does not treat this diagnosis as a recognition of the limits of American military power but rather as a rallying cry to marshal additional national resources and maintain the globe‐spanning posture to which Washington has grown accustomed. Raging against the dying light of uncontested military primacy will run into severe budgetary and strategic obstacles.

The international order faces many challenges, and these cannot be reversed by attempting to restore U.S. dominance across all domains and in all regions. Instead, U.S. grand strategy should encourage allies and partners—the leading beneficiaries of global peace and stability—to take a greater role in sustaining it. The United States cannot be the world’s police force or coast guard.

The United States needs a prudent military strategy that can protect U.S. interests without turning into an open‐ended pursuit of anachronistic, grand goals. “Overmatch” extending across all regions, domains, and weapons systems is simply untenable. The “America First” view of primacy focuses on military hardware and manpower, not the elements of smart power that have traditionally been the real sources of American strength and influence.12 Simply put, the United States today is overinvested in the military. As a recent Cato book explains, “a less expansive foreign policy agenda will allow the United States to reduce military spending significantly.”13 Washington should take advantage of the current period of relative geopolitical stability to adopt a military posture consistent with grand strategic restraint.14 Such a reorganization would bring much‐needed coherence to U.S. military strategy.

The recommendations in this report are not driven by perceptions of waste and bloat within the U.S. defense establishment—though there is certainly much of that. Rather, the authors assess international politics today as well as the probable nature of future threats and fix on what is required to defend the U.S. homeland and vital interests.

The current approach relies heavily on the use of force and coercion at the expense of other instruments of power and influence. A military‐centric strategy seems particularly ill‐suited to a post–COVID-19 world.15 The primary tools of American global engagement under a grand strategy of restraint should be trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. The military instrument, while still vital, should be geared toward defense, in the strictest sense of the word, enabling allies and partners to counter adversaries. A grand strategy of restraint would leverage innovation and modernization to refocus on a narrower range of future challenges and to rethink how strategic deterrence could better serve the needs of the nation.

Adopting a new grand strategy, and fashioning a new force posture to suit, also requires a reconsideration of the value of forward deployment. The United States should reduce its permanent overseas presence, especially in forward‐operating bases that will be vulnerable if conflict erupts. Under a strategy of restraint, the U.S. Navy and Air Force would be a surge force capable of deploying to crisis zones if local actors prove incapable of addressing threats.

The United States can support allies and prepare for future combat by enabling others to defend themselves and their interests. U.S. force planning should be oriented around how the U.S. military can contribute to such operations from a distance as U.S. interests dictate. In those rare instances where vital national interests necessitate the deployment of U.S. personnel well outside of the Western Hemisphere, Pentagon planners must ensure adequate facilities and resources to resupply their operations. Relying on forward‐deployed forces as we currently do risks inadvertently creating a security dilemma that encourages prospective rivals to match such deployments. By focusing on modernization and interoperability, U.S. forces could assist others while reducing the risk of escalation. Equally important, an over‐the‐horizon posture would reduce demands on the U.S. military—especially on active‐duty personnel.

A grand strategy of restraint calls for a less active conventional military, one that is not deployed in permanent bases or routinely engaged in offensive operations on multiple continents. Even so, restraint is not synonymous with disarmament; the United States will continue to rely on nuclear weapons to deter some strategic attacks. However, the current concept of “strategic deterrence” and the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. defense strategy would have to change. The main problem with Washington’s approach to strategic deterrence—as with U.S. military strategy in general—is that it suffers from mission creep.

At its core, “strategic deterrence” is preventing a first use of nuclear weapons against the U.S. homeland or an ally. But that is not the only behavior that U.S. officials currently seek to deter. The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), for example, says that the United States would consider using nuclear weapons to respond to “significant non‐nuclear strategic attacks” against U.S. or allied civilians, infrastructure, and early warning capabilities.16

An overly broad definition of strategic threats drives demands for a large and diversified nuclear arsenal and missile defense capability in order to have many flexible response options.17 As a result, Washington’s approach to strategic deterrence places great weight on adversary capabilities. For example, according to the 2018 NPR, “Moscow’s perception that its greater number and variety of non‐strategic nuclear systems provide a coercive advantage in crises at lower levels of conflict.”18 This is the supposed justification for new, low‐yield U.S. nuclear weapons.19 Similarly, the 2019 Missile Defense Review cites the threat of hypersonic glide vehicles—high-speed maneuvering warheads that take an unpredictable rather than ballistic route to their target and that China and Russia are developing as a response to U.S. missile defense expansion—as a rationale for deploying more missile defense sensors on satellites.20

Having a flexible nuclear arsenal and missile defense system that can be tailored to respond to the unique characteristics of different threats sounds sensible. However, the failure to prioritize produces a kind of paralysis. In a world where dangers loom around every corner, doing anything less than deterring all of them at once is considered a failure. This encourages wasteful spending and invites potential adversaries to create counter strategies that increase the likelihood of inadvertent nuclear escalation. Such moves damage deterrence instead of strengthening it. Deterrence under restraint would have a narrower set of objectives and clearer priorities and would privilege clarity and reliability over flexibility.

If the United States would prefer to engage adversaries at a distance, strategists need to rethink how the future force should be organized. Improving the ability of the different services to communicate with one another and have smoothly functioning command and control during a conflict is especially critical.21 A traditional focus on raw firepower and the impulse to base personnel and equipment at great distances from the United States will likely need to give way to an emphasis on developing a technologically proficient force that relies on new layers of sensors (radar, sonar, etc.) that can direct long‐range attacks and control unmanned vehicles at greater distances. Another overlooked capability in debates over the defense budget is the redundancy of reconnaissance systems—the ability of America’s intelligence‐gathering satellites and aircraft to perform their functions if they are disrupted.

The current approach of massive investment in the military, displays of force, and direct challenges to multiple adversaries in their respective regions is often counterproductive. As Sen. Angus King (I-ME) notes, with respect to Iran “the unanswered question is who is provoking whom. As we escalate sending more troops, moving aircraft carriers, we view it as preventative and as defensive. They view it as provocative and leading up to a preemptive attack.”22 Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution made a similar point in 2017. Arguing for a new approach to European security, O’Hanlon explained that the United States “may be able to help ratchet down the risks of NATO‐Russia war … by recognizing that NATO expansion, for all its past accomplishments, has gone far enough.”23 U.S. messaging must be consistent, and budgetary maneuvers should not introduce justifications for war. The overarching recommendation here is to halt policies that exacerbate regional security dilemmas and to restructure U.S. military power accordingly. Such a restructuring is made more difficult, however, by the rigidity of the budgeting process.

Budget Pathologies

Spending patterns driven by inertia and habit privilege the military, the use of force, and coercion over diplomacy and other instruments of American power. Accordingly, the Pentagon’s budget continues to reflect strategic errors of the past, including searching for a peer competitor, continuing support for a counterproductive war on terror, and propping up dangerous and unreliable strategic partners. To complicate matters, Congress and the White House are sparring over new distractions, including potentially diverting funds from the military budget for border wall construction24 We refer to these distractions as “budget pathologies”: abnormalities and malfunctions inherent in how the U.S. government secures funding for the military, a process that often impedes the creation of a viable national strategy. The executive branch initiates many of these pathologies, but Congress also plays a key enabling role by not exercising its traditional power of the purse.

On December 9, 2019, for example, a House and Senate conference committee passed the FY 20 NDAA. The bill authorized $738 billion for national defense spending, and President Trump proudly signed it into law.25 The U.S. government continues to spend and act as if its wars in the Middle East will never end. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper described such operations as not “necessarily unusual” and noted that “we continue … ‘to mow the lawn.’ And that means, every now and then, you have to do these things to stay on top of [the threat].”26 In fact, these operations represent sunk costs and reflect misguided assumptions about what actually makes Americans safe and prosperous.

The U.S. military budgeting process is supposed to reflect a delicate balance between executive‐level strategic guidance, Department of Defense (DOD) budget requests related to the overarching strategy, and legislative approval and appropriations to fund the requests. The actual process of funding the nation’s military, however, bears no resemblance to that ideal. A recent, clear sign of just how badly this process has broken down was revealed when the Trump administration tried to strip $3.6 billion from existing Pentagon projects to fund improvements for physical barriers at the U.S.-Mexico border. The funds earmarked to be ripped away would have served to upgrade and maintain the surface fleet, improve basic services on military bases, and expand the nation’s offensive cyber capabilities.27

This is just one example. There are many pathologies—spending decisions that serve partisan or parochial interests but do not advance U.S. security—that consistently undermine the entire federal budget, not merely what winds up in the Pentagon’s coffers. The most serious problem pertains to the unwillingness of American elected officials to reconcile spending and revenue. Despite the occasional attempt to reverse the tide, nothing has had lasting success. When Congress passed the Budget Control Act in 2011, the annual budget deficit stood at $1.3 trillion. Four years later the annual deficit fell to $438 billion. However, this figure has risen each subsequent year, exceeding $984 billion at the end of FY 19—the highest since 2012.28

Very few Americans appreciate the scale of the federal government’s spending. A poll taken in early 2017 found that only 1 in 10 Americans could correctly identify the amount spent on the military within a range of $250 billion.29 And yet, according to a 2019 Gallup survey, only 1 in 4 Americans believe that U.S. military spending should increase at all, while a slightly higher percentage (29 percent) thinks the United States is spending too much.30

The main budgetary problem for the Pentagon, therefore, is political. It refuses to budget based on what is possible and realistic and instead spends to satisfy perceptions of need (often indistinguishable from desires) with too little consideration of constraints and tradeoffs. While most Americans want a military that is prepared to prevail in combat, we all must take account of the resources available to make that a reality, both now and into the future.

Beyond this overarching problem of ends misaligned to means, the Pentagon budgeting process is afflicted by two other related pathologies: overseas contingency operations funds and reprogramming. Both allow the government to spend without consequence and fail to distinguish between needs and wants.

Overseas Contingency Operations

Supplemental appropriations to pay for wars are not a novel idea. In fact, the first was passed in 1818. Historically, however, legislators moved such “emergency” spending (today known as “nonbase nonrecurring” or “contingency” funding) for unforeseen operations back to the base military budget within a few years once leaders had a clearer idea of operational needs.31

The DOD has received $2 trillion in overseas contingency operations (OCO) funding since September 11, 2001.32 In December 2019, Congress appropriated $71.5 billion for the OCO budget in FY 20.33 To put these numbers in perspective, in 2020, if OCO were its own government agency, it would have the fourth largest budget in terms of discretionary spending.34 The use of OCO funding for almost two decades following 9/11 has systematically undermined the established appropriations process. Supplemental appropriations fund activities unrelated to the wars but are not counted as part of the base DOD budget. In other words, reliance on OCO funding lets the military services avoid setting priorities that should guide long‐term strategy and makes it too easy to undertake present‐day combat operations without formal legislative consent and funding. Other departments and agencies have also gotten into the habit; even the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Department of State now rely on OCO funding to supplement their base budgets.35 Aside from its blatant dishonesty, OCO represents a larger pattern of runaway U.S. government spending and especially the legislative branch’s tendency to avoid oversight of either Pentagon spending or the nation’s perpetual conflicts.

The other factor fueling the abuse of OCO funding is the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011. That legislation set limits on discretionary budget authority from 2012 through 2021 to slow the growth of public debt after the 2008 financial crisis.36 The spending limits are supposed to be enforced through what is commonly called sequestration. Under sequestration, any appropriations that go above set funding levels—or “caps”—are canceled.37 However, funding designated for OCO, ostensibly for counterterrorism efforts, including the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, is exempt from BCA caps and separate from the Pentagon’s base budget (hence “nonbase”).38 In other words, executive branch officials and legislators have a massive loophole for expanding military spending while seeming to abide by discretionary spending limits. The BCA’s OCO exemption allows elected officials to feign concern about out‐of‐control federal spending without doing anything to stop it.

Force development and planning requires funding that is on‐time, stable, and proportional to the scope of military operations. Using OCO to skirt the BCA’s budget caps does not reflect a military establishment that can prioritize according to coherent long‐term strategies. This technique has allowed civilian leaders to evade tough choices, including how to resolve ongoing conflicts and whether to enter new ones. While the war on terror presents unique challenges, using OCO only helps perpetuate the cycle of U.S. involvement in never‐ending conflicts.

With BCA caps officially expiring in 2021, policymakers may be less tempted to rely on OCO funding. However, moving OCO back into the base budget inevitably raises concern about overall spending increasing at an unreasonable rate. Congress should move enduring costs back to the base budget without increasing topline military spending. Presenting the DOD with less budget flexibility should spur more creativity and budget management, not less, while still allowing the military to rely on supplemental funding for truly dire, unforeseen overseas expenses. When such emergencies arise, Congress can authorize additional funds as necessary.

Reprogramming Funds

Agencies often reprogram funds to deal with unforeseen challenges, but it is technically illegal to spend taxpayer dollars in ways not explicitly authorized by Congress.39 However, “as there are no government‐wide reprogramming rules,” note Georgetown University researchers Michelle Mrdeza and Kenneth Gold, “prohibitions against reprogramming funds within an appropriations account … vary among agencies and appropriations subcommittees.”40 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) concurs. Agencies have the “implicit” authority to shift funds within a department or agency as long as the intended use of the funds remains broadly within the same goal.41 Regulations governing DOD require congressional approval for any funds reprogrammed over 20 percent or $20 million over the original allocation.

Reprogramming has become a national security issue as the executive branch seeks ways to seize control of the budget from Congress. The Trump administration’s threat to use funds allocated for other purposes to build the border wall, for example, contributed to the longest government shutdown in history in winter 2018–2019.42 Although the DOD continued operations, the budget impasse adversely affected many contractors, researchers, and production line managers.43

Past NDAAs restricted reprogramming funds for priorities that Congress expressly declined to fund, but the FY 20 NDAA did not include such language. A loophole in U.S. law allows for unassigned military construction funds to be used for construction projects during periods of national emergency.44 Other legislative language allows the secretary of defense to provide support for counterdrug activities to other departments and agencies.45 These two provisions provide the leeway to reprogram a significant amount of funding. Yet, the president can declare almost anything a “national emergency” at will.46

Thus, the moves to reprogram funds defy Congress’s traditional power of the purse and allow federal agencies to use money from the DOD budget to support domestic political initiatives. Such efforts create a dangerous precedent, both in undermining constitutional checks and balances and potentially limiting the funds vital to the nation’s defense.

Building a Modern Military for Restraint

These budgetary pathologies insulate the U.S. military from resource constraints, allowing it to proceed mostly by inertia. But the U.S. military also remains mired in the post‐9/11 Global War on Terror. Nearly two decades of continuous operations have put enormous strain on the force. The military branches continue to lower eligibility requirements to meet their recruitment goals and have increased retention bonuses to discourage services members from leaving.47

More ominous developments include rising suicide rates among veterans and active‐duty service members, an increase in reported sexual assaults, and the need for expanded counseling to deal with post‐traumatic stress disorder and other psychological challenges.48 In short, the well‐being of U.S. service members is a pressing national concern.

The force of the future is likely to be smaller, particularly in terms of numbers of personnel in uniform, and thus will need to be more adaptable. That, in turn, will require increasing the academic aptitude and physical fitness standards for recruits.49 A focus on improving the force—as opposed to simply growing it—through retention programs for critical staff and expanded educational and retraining opportunities is key to creating a healthy and socially viable military. This should be a DOD‐wide imperative.

Beyond recruitment and retention, each service branch confronts its own unique challenges. Pentagon officials must reconceptualize how the U.S. military plans to fight. The wars of the recent past, against chiefly nonstate actors in the greater Middle East, South Asia, and Sub‐Saharan Africa, are unlikely to be an adequate guide for future conflicts.

In particular, the potential for direct engagement with technologically capable adversaries in contested environments means that the era of U.S. dominance can no longer be assumed. Within that framework, the following sections outline a few key choices that service leaders need to make.

Modernizing the Joint Force

There are two clear challenges for the joint forces of the United States: standardizing a system for operations across multiple domains (e.g., land, sea, air, space, and cyber) and pushing innovation. Addressing the first challenge demands that every branch of the U.S. military agrees to a joint, all‐domain command and control (C2) system. As combat systems and advanced artificial intelligence (AI) platforms continue to develop, they must be seamlessly integrated within and between all U.S. forces. Currently, however, each military branch is pursuing its own C2 design. For example, the Navy has the Naval Integrated Fire Control‐Counter Air system, and the Air Force has the Advanced Battle Management System.50 This duplicates effort, wastes funds, and impedes unifying C2.51

Defense contractors and other interested parties will lobby for their respective systems, but the choice should be based on the ability to implement the system across all services, agreement among the branches, and a clear standard for cybersecurity. Because a standard C2 platform is the optimal solution for the modern battlefield, all U.S. forces should streamline and upgrade to ensure that they meet the new compatibility standards. The U.S. military should not move forward with designing protections for these networks, and redundancy for forward C2 deployment, without first establishing a joint system. It is premature to estimate the eventual cost of such a unified system, but deciding on this system now will inevitably save money by facilitating coordination between every branch of the U.S. military.

The DOD, for its part, must decide on a platform, take bids on delivery of the system, and obtain executive branch and congressional approval on a process and timeline for implementation. Congress should use its legislative authority to ensure compliance through reporting requirements.52

The second overarching challenge for the U.S. military is the need to prioritize innovation. This entails empowering individuals at all levels to bring forward new ideas and establishing a process to deliver design options through a full development cycle in the most expeditious and cost‐effective ways. Service members have a critical role to play in determining future priorities since these systems and platforms will have a direct impact on their daily lives and their ability to function on the battlefield.

Following the Army’s example, each branch of the military should develop its own Futures Command to push for branch‐wide innovation. The mission of a Futures Command is modernization. It does away with old “industrial age” approaches, which are mostly piecemeal and often slowed by bureaucracy, and puts them all under one roof with a set of defined goals. If each branch has its own innovation command center, the Pentagon would be well‐positioned to coordinate across branches. A futures reserve unit in each branch would prove critical given the recent effort to recruit and fund PhDs in the military and DOD.53 Members of the armed forces with advanced degrees could then naturally transition into the reserve system to support innovation.

The service branches should also develop practices for curating the massive amounts of data generated for AI systems. Given the high probability that this technology will be critical to future fights, branches should use “data wranglers”—individuals whose primary task is to collect information that can be plugged into various systems.54 There is currently no method to identify U.S. service members able to work with data, generate statistical analysis, and assure the accuracy of data.

In addition, Kessel Run‐type programs in each branch could be successful for fostering innovation, as it has been for the Air Force. In the Star Wars universe, the Kessel Run refers to an impossible task that is completed in a short time. The Air Force had that in mind when it set out to develop software quickly and in response to an uncertain environment.55 The inability to negotiate contracts with external parties who will build software or hardware in a timely and efficient manner are typically the main impediments to developing innovative programs in the military.

Making Innovation a Priority

U.S. defense planners should consider what the nation’s defense needs will be in the future, but too often their efforts are stymied by inertia or shortsighted demands that defense programs serve domestic political and economic interests. The United States should be investing in innovation and research rather than stale production lines for weapons that have outlived their usefulness or new weapons that can never meet their design objectives.56 Developing weapons platforms should be based on the needs of the future military, not short‐term concerns, such as the parochial interests of defense‐industry workers or the politicians who shield them. The U.S. military must abandon weapons platforms that cost too much to maintain and retrofit and have limited or no value in future conflicts.

Future increases to the DOD’s research and development (R&D) budget should be funded by reducing spending on outdated weapons systems. As part of a renewed push for R&D, the U.S. government should revisit its approach to basic research funding. Instead of bolstering the National Science Foundation and encouraging scholars to seek trivial connections to national security in research projects, the DOD should be granted additional authority to invest in other public and private research startups and incubators through the individual service research offices (e.g., the Office of Naval Research). These funds should not be restricted and should be open to every research university and think tank capable of doing advanced research that will help drive innovation within the defense ecosystem.

This is not an argument for expanding federal funding for research but rather extending existing research opportunities to a much wider pool of qualified institutions. For too long the U.S. government has steered research funding to federally funded R&D centers. This has driven up R&D costs while failing to integrate the talent and ingenuity of research institutions outside traditional networks. The United States must leverage its deep technological base to meet coming challenges; as of now the U.S. government’s vision of research and research funding is tied to past processes that have a decidedly mixed record of delivering essential equipment and materials in a timely and cost‐effective manner.

Research should be focused on applying novel technical capabilities to the modern battlefield. The idea that the United States has fallen behind China in the AI arms race is only true based on a measurement of research quantity, not quality. And such claims do not take full account of the vast array of innovative enterprises in the United States, most of which are completely outside the federal government’s control or purview.

For example, Google recently published a paper demonstrating quantum supremacy, when a quantum device (such as a quantum computer) can solve a problem that no traditional computer realistically can.57 This represents a leap over classical computing power by orders of magnitude, but U.S. defense planners must think about how to employ these tools in combat. AI is only as useful as the data fed into the algorithms.58 Moving forward with a clear vision of how the U.S. military can leverage AI and quantum power, therefore, requires investments in basic data science education, data assurance and retention, and data integrity.

These proposals are generally cost‐neutral as they entail reorganization of existing lines of effort. Ensuring that the U.S. military develops multidomain battle systems without redundancy, establishing a clear process for managing data on the battlefield, and putting platform development in the hands of the individual soldier, sailor, airman, and Marine are all clear needs as relevant as massive outlays for modern weapons platforms. Reorganizing around Futures Command groups and using data wranglers would enable all service branches to innovate as the United States still enjoys a number of political, economic, and strategic advantages relative to prospective rivals.

The Air Force

Since its formal inception in 1947, the Air Force has fended off challenges to its place in the structure of the U.S. military, and a few respected scholars still call for its abolition.59 Many critics, however, aim to fix apparent inefficiencies within the force rather than doing away with it. A recent Center for Strategic and International Studies report, for example, notes that while spending on the Air Force has reached new heights, its force capabilities—as measured by the number of aircraft in its inventory—have fallen to an all‐time low.60 This is partly explained by the overall focus on quality over quantity but is also due to the fact that the Air Force is more than just planes, just as the Army is more than the infantry and the Navy is more than surface ships. Still, the Air Force has struggled to introduce new aircraft. The service’s experience with the F-35 Lightning II aircraft, a fifth‐generation fighter jet that is significantly more advanced than its predecessors and supposed to replace several other aircraft currently in service, has not been promising. In general, the Air Force has spent a lot of money to get less capacity.

A change of direction is in order. The structure and capabilities of the Air Force should maximize operational readiness, taking into consideration procurement difficulties associated with current weapons systems still under production.61 The bitter experience with the F-35, which will be delivered to the force nearly a decade late and at an inflation‐adjusted cost well above original estimates, is only one sign of the overall challenge facing the Air Force.62 The service needs capable aircraft at a cost that will allow it to purchase them in adequate quantities, and it needs to obtain them in a timely fashion.

Per the objectives spelled out in the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), the U.S. Air Force is tasked with dominating the air, outer space, and cyberspace by using advanced and emerging technology. The Air Force needs to be an innovative service to keep up with the rapid pace of technical change. Specifically, the service should focus on countering China and Russia’s investments in anti‐access/area‐denial systems, including long‐range surface‐to‐air missiles.63

This will be difficult. As previously noted, the Air Force’s rising budgets have coincided with a declining number of active aircraft, along with fewer pilots and Air Force civilian employees.64 Such trends signal broader challenges with basic budgetary management, including the expanding costs of operation and maintenance. In other words, today’s Air Force paradoxically does less while spending more. This is perplexing to say the least.

While the service has emphasized incorporating advanced technology for air and space operations, overall readiness and pilot training have decreased substantially, contributing to a steady rise in aircraft mishaps.65 These operational problems are exacerbated by a shortage of qualified maintenance technicians. According to the GAO, the Air Force does not have a strategy to improve retention. If the Air Force is unable to hold onto its best people, it will struggle to adapt to changing operating environments (including outer space and cyberspace) and new technology (such as AI and quantum computing).66 The Air Force must undertake a service‐wide initiative to reverse this trend, especially by incentivizing qualified personnel to remain in the force.

With respect to hardware, the Air Force is developing the F-35A, the B-21 Raider long‐range bomber, and the KC-46A Pegasus tanker aircraft while also seeking to replace current intercontinental ballistic missiles and developing a Space Force, which is still officially under the Air Force’s auspices. That is unsustainable. The service’s goals must be aligned to present and future realities and should take account of the demands of modern combat. As the airspace in which the Air Force operates becomes increasingly crowded and contested, this places a premium on unmanned vehicles that can loiter and are capable of executing strike, surveillance, and resupply missions.

Forward basing poses both operational and doctrinal challenges to air operations because long‐range precision strikes by an adversary can decimate aircraft and fuel supplies long before U.S. aircraft can engage the target. What good is a force of 100 F‐35s if they never leave the ground?

A focus for now on drones and a reliance on a revitalized F-15 Eagle aircraft through the F-15EX platform is certainly warranted. The recent move to establish the 16th Air Force, which is focused on cyberspace and electronic warfare, is also a welcome development.67 On the whole, however, the Air Force is trying to do too much, including a focus on space, support for counterterror operations, unmanned reconnaissance, nuclear deterrence, transport, air defense, air‐to‐air combat, ballistic missiles, and precision bombing. A strategic pause and reset are desperately needed.

The Army

The Army’s strategy, posture, and budget should reflect and adapt to evolving geopolitical circumstances. The U.S. Army posture assessment fails to do that, placing dominance through military overmatch, as outlined in the NDS, at the forefront of the Army’s vision.68 Day‐to‐day operations, ongoing conflicts, allied engagement, and crisis response all continue to put unnecessarily high demands on the force. A realistic assessment of threats would allow the Army to prioritize and eliminate or offload unnecessary missions. Enabling and encouraging allies to do more in their respective regions would reduce the Army’s requirements, including especially numbers of active‐duty personnel.

In 2018, the Army created the Army Futures Command.69 This organization has been critical for pushing the service to modernize. It originally established six priorities:

long‐range precision fires (i.e., enhancing the ability to accurately deliver ordnance against even well‐defended targets);

next‐generation ground combat vehicles;

future vertical lift (including helicopters and other air platforms for delivering troops and equipment to the battlefield);

command, control, and communication within a network optimized for modern combat;

air and missile defense; and

soldier lethality (i.e., enhancing the individual soldier’s ability to fight, win, and survive).70

Of these, long‐range precision fires (i.e., modern artillery) and networked air and missile defense are critical. The United States should divest from other outdated weapons systems—including, in particular, the Abrams tank—that are unlikely to serve a major purpose on the future battlefield, or at least in the battlefields that are truly critical to U.S. security and prosperity.

Above all, the active‐duty U.S. Army should be substantially smaller and postured mostly for hemispheric defense. A grand strategy of restraint would eliminate most permanent garrisons on foreign soil and rely more heavily on reservists and National Guard personnel for missions closer to the U.S. homeland. Such a posture would reduce the likelihood that U.S. troops would be drawn into protracted civil conflicts that do not engage core U.S. national security interests. That, in turn, would generate substantial savings over the next decade.

Developing better and modern versions of artillery is another key task for the Army. That would allow the U.S. military to support allies from a distance, when U.S. leaders deem such assistance appropriate, while also ensuring that U.S. troops mostly remain out of harm’s way when such missions are not truly essential for U.S. security.

The development of better unmanned vehicles for long‐range fires in support of ground operations is also critical. While drones for surveillance and precision strikes are useful, in a future war the United States will need functional unmanned vehicles that can deliver artillery support and fire weapons from a distance, minimizing harm to U.S. forces. Future platforms used to deliver long‐range fires also need the ability to be undetected despite increased sensors employed by adversaries.

Finally, the Army needs to develop better air and missile defensive platforms to protect forward‐operating units. These tools would benefit the entire U.S. military, but the greatest gain would go to the Army, whose ability to fight will be challenged by opponents’ long‐range munitions. The Army needs portable sensors ready to detect incoming fires. A modern military is too vulnerable to long‐range attack, including from artillery, ballistic missiles, and drones. Real‐time battlefield awareness is essential, as is the need to defend our allies once the U.S. commits to pulling back from forward deployment. Thinking about this critical function is more important than developing a new helicopter or other vertical lift platform (e.g., tilt‐rotor aircraft) or a next‐generation tank. If the U.S. military cannot protect its forces in the field from short‐range ballistic and cruise missiles, units will not survive long enough to bring these new weapons to bear against the enemy.

To meet current recruitment goals, the Army has waived certain requirements and increased enlistment bonuses.71 If these reforms draw capable people into the service, then they should continue, but careful oversight is needed. An emphasis on quality, rather than quantity, could reduce turnover, ensure new enlistees complete their requisite training, and ultimately improve retention.

A focus on readiness could also help. Service members should know that they have adequate support to complete their missions and be confident that policymakers will not send them to fight open‐ended wars that are not vital to U.S. national security. A failure to meet those basic requirements has driven qualified personnel from the force. No branch of the U.S. military has reached its readiness goals, however, and the budget priority has since shifted to modernization. While the increase in research, development, testing, and evaluation is an important step in creating a more lethal and agile force, a failure to meet readiness goals will impede force transformation.

The Army needs to rethink the size of the force needed given the effort to modernize overall. At a time when two successive presidential administrations have pledged to draw down operations in the greater Middle East, the United States should refocus on establishing a lean and agile ground force that can retain the best people while allowing the marginal performers to transition out. This process of attrition should be used to reduce the size of the active‐duty Army by 20 percent over the next decade. Recruiters need to employ what marketers call “microtargeting” to ensure that the U.S. Army has high‐quality soldiers that can innovate on the battlefield, not just follow orders.72 Eliminating unnecessary forward bases, improving existing facilities, and rethinking education and training would be easier with reductions in the size of the force.

The Navy

In recent years, the U.S. Navy has operated under the assumption that it can get all that it wants without a clear articulation of what it needs—though the situation may be changing. An October 2019 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report warned that the Navy “would not be able to afford its 2020 shipbuilding plan.” CBO estimated that the Navy would need $28.8 billion per year for new‐ship construction, more than double the historical average of $13.8 billion per year (in 2019 dollars).73 This is hardly the first time that CBO has observed the looming gap between the Navy’s plans and fiscal realities.74 Although the sea service has avoided a bitter reckoning, the responsible course would bring its goals in line with its available resources.

In early December 2019, Acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly publicly reaffirmed his commitment to achieving a 355‐ship Navy, and he separately issued a memo to the fleet calling for a plan to achieve it by the end of the next decade.75 But more recent evidence suggests that the Trump administration has scaled back its shipbuilding plans and backed away from the 355‐ship goal. The president’s budget submission for FY 21 actually cut $4.1 billion from shipbuilding.76 Navy leaders acknowledge the tradeoffs between operations and maintenance and money for new construction. “We definitely want to have a bigger Navy, but we definitely don’t want to have a hollow Navy either,” Modly told Defense News. “If you are growing the force by 25 to 30 percent, that includes people that have to man them. It requires maintenance. It requires operational costs. And you can’t do that if your top line is basically flat.”77

Many strategy documents simply assume that considerably more money must be made available to the military—and leave it to the politicians to figure out how.78 The Heritage Foundation, for example, calls for a 400‐ship Navy even as it concedes that such a force “may be difficult to achieve based on current DOD fiscal constraints and the present capacity of the shipbuilding industrial base.”79

The Navy should reject such advice, prioritize among competing desires, and focus on what is genuinely needed to achieve vital national security objectives. In the near term, this means prioritizing current operations. High‐profile disasters at sea, including the tragic accidents aboard USS John S. McCain and USS Fitzgerald, which claimed 17 sailors’ lives in 2017, raised obvious questions about the state of the surface Navy. A GAO report released two years before the McCain and Fitzgerald incidents concluded that “the high pace of operations the Navy uses for overseas‐homeported ships limits dedicated training and maintenance periods,” which had “resulted in difficulty keeping crews fully trained and ships maintained.”80

The Navy must expand both its capacities and capabilities. Prioritizing less‐expensive vessels could make up for certain shortfalls and grow the fleet at a faster rate. Newer platforms would also translate to less maintenance time, further increasing the number of vessels ready for service at any given time. On occasion, the Navy has gone in a different direction, privileging very high‐end platforms that often take many years to reach the fleet. In the interim, this leaves more older ships in service longer, along with their additional repair and maintenance costs.

The Navy has made recapitalizing the ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) fleet—the Columbia-class SSBNs that will replace the Ohio-class—its top shipbuilding priority. The tradeoffs are most apparent with respect to fast‐attack submarines (SSNs).81 Although these vessels are unsuited to perform many routine Navy missions—including escort operations and visible presence—they are critical and should be maintained in some quantity.

Other hard choices cannot simply be imagined away. This report focuses on two key acquisitions programs to highlight tradeoffs within the surface fleet: the Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carrier (CVN) and the new guided‐missile frigate FFG(X).82

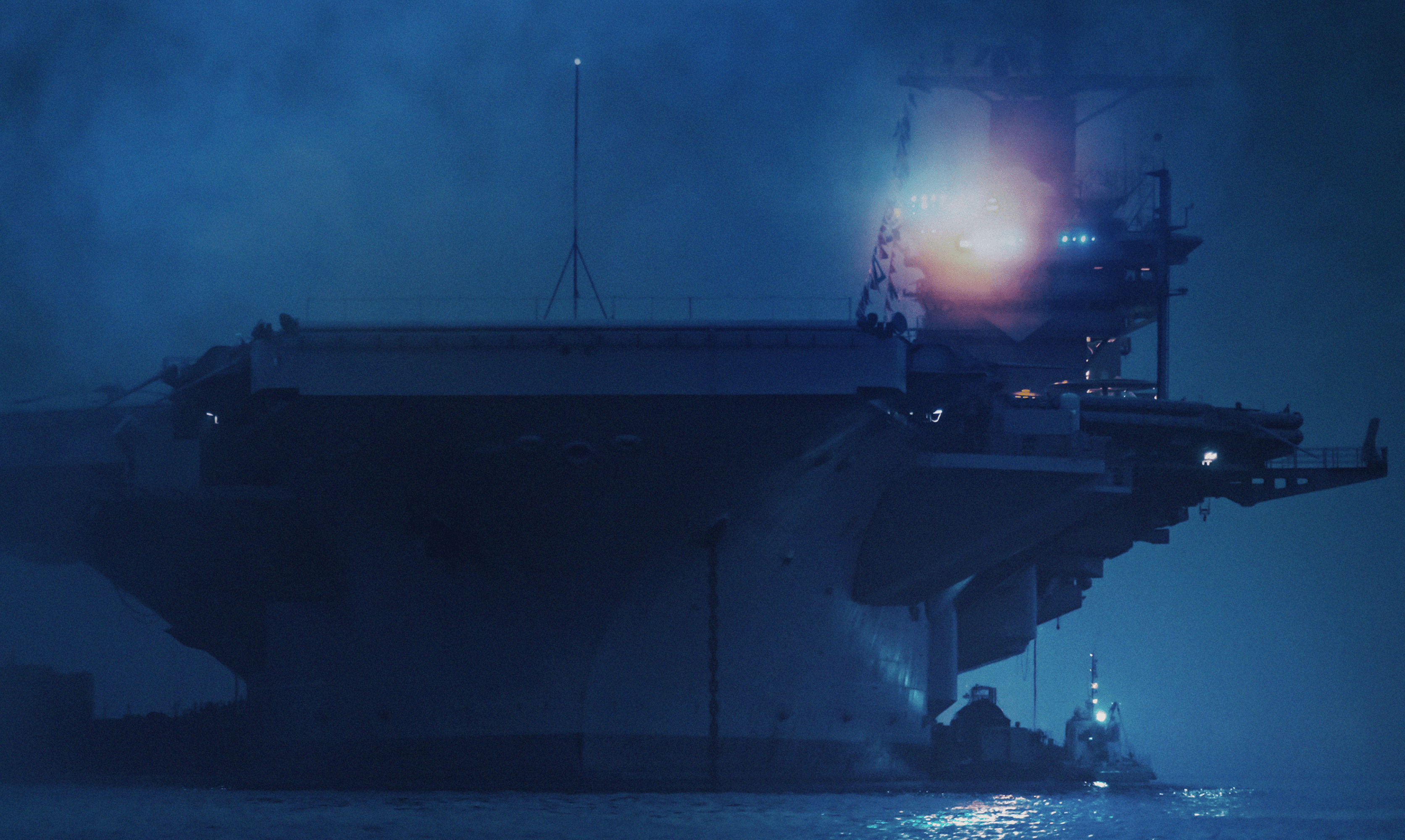

The Gerald R. Ford-class Aircraft Carriers

As designed, Ford-class ships are the largest and most capable warships on the planet. But little else about the ships—including whether their actual performance matches their designed capabilities or when the ships will attain full operability—can be predicted with any confidence. Former Navy Secretary Richard Spencer staked his reputation on ensuring that the advanced weapons elevators—large lifts that transport bombs and missiles from inside the ship to the flight deck—aboard USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) would all work before the ship set out for trials. They didn’t—only 4 of 11 were operational by the end of October 2019.83

Three other critical technologies—the ship’s new electromagnetic aircraft launching system, an advanced arresting gear used to recover aircraft on deck safely, and a dual band radar—have also failed to meet the service’s expectations.84 A December 2018 report by DOD’s director of operational test and evaluation (DOT&E) identified a host of concerns, ranging from “poor or unknown reliability of systems critical for flight operations” to inadequate crew berthing.85

Most damning, perhaps, were the DOT&E’s conclusions pertaining to the ship’s core mission: the ability to launch and recover aircraft at high tempo and over extended periods (sorties, in Navy jargon). The report warned, “Poor reliability of key systems … on CVN 78 could cause a cascading series of delays during flight operations that would affect CVN 78’s ability to generate sorties.”86 In the end, DOT&E concluded that the Navy’s sortie generation requirements for the Ford were based on “unrealistic assumptions.”87

Other critics fault a systemic lack of accountability throughout the Navy. Industry analyst Craig Hooper wrote in October 2019, “The naval enterprise struggles to bring bad news to the higher levels of the chain of command. It is a habit that perpetuates something of a complacent ‘not my problem’ or career‐protecting sluggishness in the face of avoidable disaster.” This has ramifications that go well beyond catapults and arresting gear.88

As difficult as the design and development process for the Navy’s capital ship has been, however, even tougher questions swirl around the employment of these massive platforms. In an era of defense dominance, when adversaries can use relatively cheap but accurate weapons to attack large and exquisite platforms, how will the carriers perform? Not well, according to some knowledgeable critics, including retired Navy Capt. Henry J. Hendrix, who in 2013 warned, “The queen of the American fleet is in danger of becoming like the battleships it was originally designed to support: big, expensive, vulnerable—and surprisingly irrelevant to the conflicts of the time.” The national security establishment, he concluded, had ignored “clear evidence that the carrier equipped with manned strike aircraft is an increasingly expensive way to deliver firepower” and that the ships might struggle “to operate effectively or survive in an era of satellite imagery and long‐range precision strike missiles.”89

National Defense University’s T. X. Hammes imagines an even more dramatic transformation that would merge “old technologies with new to provide similar capability at a fraction of the cost.” Specifically, Hammes proposes using container ships loaded with hundreds or thousands of drones and cruise missiles—but very few people—to eventually take the place of the iconic flattops hurling and recovering manned aircraft. “Flying drones,” Hammes writes, “can provide long‐range strike, surveillance, communications relay, and electronic warfare” and can be launched and recovered vertically. Cruise missiles deployed in standard shipping containers, meanwhile, could effectively convert “any container ship—from inter‐coastal to ocean‐going” into “a potential aircraft carrier.”90

For now, Congress has conspired to thwart any fundamental reconsideration of the centrality of the aircraft carrier to the modern surface fleet. The 11‐carrier legislative mandate remains despite serious concerns about the Ford’s timeline and even as “the Navy is finding it increasingly difficult to deploy carriers and keep them on station.”91 A reckoning has been postponed but cannot be avoided forever.

The Next‐Generation Frigate

According to the Force Structure Assessment issued in December 2016, the Navy seeks to procure 52 small surface ships, 20 of which are to be a new class of guided‐missile frigates, the FFG(X).92 Some analysts contended that reactivating the Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates, the last of which was retired in 2015, would help the Navy achieve its force structure goals faster, but the decision to commission new vessels signaled the Navy leadership’s commitment to modernization.93

The Navy requested $1.28 billion in its FY 20 budget to procure the first FFG(X), awarding conceptual design contracts to five different companies.94 Despite the purported reduction in scheduling, risk, and price with the Navy’s approach to the FFG(X), the CBO predicted in October 2019 that the total cost of the 20‐ship program will be closer to $23 billion than the Navy’s estimated $17 billion.95

Although the House and Senate fulfilled the administration’s request for $1.28 billion in procurement, plus another $59 million for research and development in the FY 20 NDAA, doubts remain about this program’s ability to fill the capability gaps in the fleet.96 The key questions will revolve around unit cost and the length of the design, development, and build phases. Congress has put significant pressure on the Navy to implement cost‐effective capabilities on realistic timelines. If the Navy is truly committed to expanding fleet capacity quickly, and with minimal risk, it is imperative that it hold the line against anything likely to lead to costly delays.

Ending the Global Coast Guard

Before the Navy can decide what it needs, however, it must decide what it’s going to do. The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy (NSS) and NDS would appear to be good news for the Navy. Both documents focus on the rise of peer or near‐peer competitors, chiefly China and Russia, with reference also to regional rivals such as North Korea and Iran. These types of adversaries would privilege the need for naval and air power over ground forces, which have been geared to fighting nonstate actors and insurgents over the past two decades.

The U.S. Navy has an extraordinarily ambitious set of objectives, and the demands placed on the service already exceed its ability to meet them. These demands mostly originate with the various regional combatant commands and further reflect a long‐standing assumption that the Navy’s forward presence is essential to global security. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of U.S. Military Strength, for example, argues that “the Navy must maintain a global forward presence both to deter potential aggressors from conflict and to assure our allies and maritime partners that the nation remains committed to defending its national security interests and alliances.”97

What the Heritage Foundation casts as a requirement is a choice. Strategic requirements are not handed down from on high but reflect the dominant strategic paradigm. A commitment to maintaining the free movement of raw materials, essential commodities, and finished goods was a core mission for the U.S. Navy during the Cold War and was driven by a concern that a globe‐straddling Soviet Navy was both motivated to close—and capable of closing—critical sea lanes of communication and maritime choke points.98

Today, the situation is much different. Most international actors, including even modern rivals such as Russia and China, depend on the free flow of maritime trade and are therefore highly incentivized to try to keep these waterways open. For decades, however, U.S. allies and partners have neglected their own maritime forces, coming to rely on the U.S. Navy deploying small, surface combatants in their home waters. In effect, therefore, the U.S. Navy has been operating as a global coastal constabulary.

This practice should stop. U.S. policy should aim to encourage these nation‐states to play a key role in securing access to vital sea‐borne trade. The presumption that the U.S. military must be constantly on station, including in waters thousands of miles away from the Western Hemisphere, merits scrutiny, not least because the U.S. Navy alone cannot meet the demands of being a de facto coast guard for all other nations—nor is it in America’s interest to try.

Sea‐lane control in the modern era aims to ensure the free flow of goods and is primarily defensive. The aim should be to prevent others from limiting access to the open oceans while not threatening to deny anyone else the peaceful use of those same seas. That mission can and should be shared with other countries, most of whom will be operating near their shores, and thus highly motivated—and able—to defend their sovereign waters.

The Marine Corps

Marine Corps Gen. David Berger’s appointment as the 38th commandant of the service was met with a question by a Marine Corps major: “Sir, who am I?”99 With a founding mission of being able to carry out contested amphibious operations, it is unclear today who the United States is preparing to invade, and how it would do so. Would the United States deploy landing craft like those used on Normandy beaches in 1944 or at Inchon Korea in 1950 during an age of highly sophisticated surface‐to‐surface missiles? Does the U.S. military have functional aviation or naval vehicles that can support large modern amphibious invasions?

The response to these sorts of questions was dramatic and forceful. Berger’s Commandant’s Planning Guidance (CPG) sought to kill many sacred cows and institute a new path forward where the Marines would focus on sea denial, interoperability with the Navy, and wargaming to understand current and future combat options.100 The CPG stated, without evocation, “the Marine Corps will be trained and equipped as a naval expeditionary force‐in‐readiness and prepared to operate inside actively contested maritime spaces in support of fleet operations.”101

The Marine Corps’ decision not to request amphibious platforms in the 2020 budget was formalized in the CPG, which called amphibious operations “impractical and unreasonable.” Such conclusions recognize the need for a swift, agile force that can operate in forward positions without the resources and protection of the core force.

While a future great power war in the Asia‐Pacific is possible, the probability of a near‐term conflict is very low; this supports the decision to move the Marine Corps from a focus on amphibious operations. In fact, recent reports note that China’s navy is rethinking its spending plans given the economic uncertainty brought on by the trade war with the United States.102 China is not a peer competitor; its grandiose naval ambitions remain unfulfilled, as massive investment would be needed for surface ships, landing craft, advanced weapons platforms, aircraft, and personnel—all when the demands of an expanding middle class are increasingly going unmet. And those domestic challenges all preceded the COVID-19 pandemic that began in late 2019 that has wreaked havoc on China’s economy.

As Marine Corps planners recognize, there is a great need for large numbers of cheap autonomous naval systems that can overwhelm the enemy, and these are preferable to expensive and manned systems.103 Berger stated, “I see potential in the ‘Lightning Carrier’ concept … however, [I] do not support a new‐build CVL [light aircraft carrier].”104 The CPG suggests a possible focus on high‐mobility artillery systems to deny sea access and landing routes.

The Navy and Marine Corps should not be pushing new amphibious platforms when they are unable to maintain their current craft in a steady state of readiness.105 If the Marines are truly the “first to fight,” they need to focus on modernization, rework force structure for quality over quantity, and reset their priorities after years of focus on the Global War on Terror. Senior leaders in the Marine Corps have the correct vision, but implementing their plans within a change‐resistant bureaucracy will be a challenge.

The Future of Strategic Deterrence

The United States has failed to undertake a much‐needed reevaluation of its approach to strategic deterrence. The nuclear triad, the array of land‐, air‐, and sea‐based capabilities that can deliver nuclear weapons to targets, has been a fixture since the early Cold War. Since then the triad has become dogma. A reexamination of its value considering technological developments, advances in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, and changes in adversary capabilities is overdue.

That hasn’t occurred under the Trump administration, which seems to be settling on a kitchen‐sink approach to solving the country’s alleged “deterrence gaps” vis‐à‐vis other great powers.106 Its 2018 Nuclear Posture Review retains the triad and adds two new capabilities—a low‐yield warhead for the Trident (the nuclear‐armed ballistic missile carried by U.S. submarines) and a new nuclear sea‐launched cruise missile—to the Obama administration’s nuclear modernization plan. A 2017 report from the CBO estimated that this plan would cost roughly $1.2 trillion over 30 years.107 That 30‐year estimate is likely to increase as programs face unforeseen problems and delays. The United States is also trying to improve its capabilities for defeating ballistic and cruise missile threats to both forward‐deployed forces and the American homeland.108

These investments in nuclear weapons and missile defense demonstrate that strategic deterrence remains central to U.S. strategy, but is the United States making the right policy choices? What are the threats the United States wants to deter, and can nuclear weapons and missile defense help mitigate them? Raising these questions reveals that some elements of the nuclear modernization plan are superfluous and that some missile defense choices are likely to push rivals to develop destabilizing counterstrategies.

Most of the nuclear modernization plan’s spending will fund new delivery platforms—aircraft, submarines, and missiles—with some money going toward updated nuclear warheads. The plan is not meant to expand the arsenal; as new systems get introduced, old ones will be phased out.

Supporters of the nuclear modernization plan claim that it will only eat up a small portion of overall military spending. That is true given the very high topline for the budget, but this does not imply that nuclear modernization will be cheap and easy. Initial cost estimates are already growing. For example, recent delays in the B61-12 nuclear gravity bomb life extension program (LEP) will add an extra $600–$700 million, and the W80-4 nuclear warhead LEP’s estimated project cost had increased from $9.4 billion in November 2017 to $12 billion by summer 2019.109 Delivery platforms are also prone to cost overruns. The B-2 Spirit bomber program (which wildly overran its initial cost projections) offers a cautionary tale for its secretive and expensive successor, the B-21 Raider.110

Before developing new nuclear capabilities, we need to decide whether they are necessary for strategic deterrence. Arguments about the relatively low price of systems are hardly compelling if the United States does not need to buy them in the first place. The B61-12 gravity bomb, for example, is superfluous given U.S. efforts to develop an air‐launched cruise missile that could hold the same targets at risk from long distance.111 The decision to deploy a low‐yield tactical warhead for the Trident missile rests on faulty understandings of Russian nuclear strategy.112 Similarly, the United States should eliminate the nuclear mission for the F-35, cut the purchase of new intercontinental ballistic missiles in half, and delay procurement of the B-21 for 10 years.113

Increased spending on strategically dubious capabilities also extends to missile defense. The 2019 Missile Defense Review calls for a wide‐ranging expansion of missile defense capabilities to counter both rogue states and great powers.114 That includes expanding the stock of existing interceptors and developing new technology to counter offensive capabilities that U.S. adversaries have fielded to defeat existing U.S. defenses.115 Rather than enhancing strategic deterrence, America’s missile defense posture is encouraging adversaries to develop new offensive platforms that increase the risk of conventional conflicts going nuclear.

Strategic Deterrence under Restraint

Adjusting American grand strategy toward restraint would mandate a different approach to strategic deterrence. Modernizing the U.S. nuclear arsenal is important, but the pursuit of maximum flexibility to deter an amorphous set of strategic threats will waste billions of dollars on capabilities the United States doesn’t need. The primary goal of strategic deterrence, preventing nuclear first use against America and its allies, would remain the same under restraint. Instead of pursuing flexibility to respond to a wide variety of threats, the three pillars of strategic deterrence under restraint are removal of peripheral threats through diplomacy; shifting a greater defense burden to allies; and adopting a conventional military posture that enables deterrence by denial—discouraging enemy action by denying a quick and easy victory.

Greater reliance on diplomacy could contain or remove potential threats that current U.S. military doctrine casts as strategic imperatives. For example, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran allowed the United States to reduce nuclear proliferation risks through diplomacy.116 The case also illustrates the negative consequences of abandoning diplomacy. Since the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the agreement, the region has witnessed a constant tit‐for‐tat escalation of tensions.117 Arms control agreements with other great powers such as China and Russia are another important feature of restraint’s approach to strategic deterrence. Arms control measures can help set guardrails on the most dangerous aspects of great power competition, allowing for a degree of strategic trust and stability that is important for averting nuclear disaster.

Another key component of a redesigned U.S. strategic deterrent would entail empowering allies to respond to the coercive activities of regional rivals. Given the stakes involved for all parties, the deterrent threats by local actors might prove more credible than those issued by a distant United States.118 Under restraint, regional disputes might prove less likely to escalate into great power conflict, and more capable local deterrent forces would help reduce—though not eliminate—demands on the U.S. military and U.S. taxpayers.

China and Russia demonstrate how effective asymmetric strategies—those that avoid matching an opponent’s capabilities but instead try to exploit weaknesses with other means—can frustrate an otherwise stronger foe that depends on power projection to achieve its interests.119 U.S. allies in East Asia, for example, don’t need to build a lot of expensive aircraft or ships to defend themselves from China’s growing air and naval forces. A mix of unmanned systems, long‐range precision strike conventional weapons, and strong air defense could be an effective and affordable counter to Chinese power. Encouraging allies to develop their own asymmetric capabilities would empower them to contribute more to deterring regional conflicts. Gradually reducing the forward deployment of U.S. forces could facilitate this transition.120

The United States would still have an interest in deterring nuclear first use against its allies—or the use of nuclear weapons in any context. But stronger, more capable allies armed with conventional weapons, combined with a reduced forward‐deployed U.S. military presence, would shorten the list of strategic threats that U.S. officials feel obliged to deter or eliminate.

The third pillar of a new U.S. strategic deterrence posture under restraint is a greater reliance on conventional weapons to deter other great powers. Instead of threatening an attacking country through punishment (damaging the attacker’s population and economy) this approach would depend on a concept known as deterrence by denial, which resists enemy action by denying a quick, easy military victory for the aggressor.121 Credibly increasing the costs of aggressive action would leverage U.S. advantages in sensors, regional missile defense, and conventional long‐range precision strike to deter military action that U.S. allies are unable to address.122 Allies equipped with similar capabilities would further improve deterrence by denial.

Such an approach would reduce the risk of inadvertent nuclear escalation in conventional conflicts by focusing on defeating military units rather than engaging in deep strikes against an adversary’s command and control networks.123 Technical developments in both the United States and its potential great power adversaries have blurred the lines between conventional and nuclear forces. The military strategies adopted by the United States, China, and Russia that emphasize early, deep conventional strikes further increase the escalation risks.124

Under this new approach, nuclear weapons and homeland missile defense would play reduced roles. On the missile defense side, U.S. defense planners should pivot to improving regional systems and increasing the stock of associated interceptors while moving away from expanded homeland missile defense.126 That would make it harder for great power adversaries to both initiate and prevail in quick, limited conflicts. U.S. leaders would also face less pressure to rapidly escalate to conventional attacks against Chinese or Russian territory. The U.S. way of war emphasizes strikes against command and control facilities, some of which are located far behind a country’s borders. Such strikes could be interpreted as an attack on a country’s leadership or an effort to reduce the effectiveness of its nuclear forces. If U.S. forces could deflect an initial attack against land‐based, anti‐access/area denial weapons such as surface‐to‐air and anti‐ship missile batteries, it could reduce the incentive to target adversary command and control early in a conflict.

Conclusion: Building for the Future