Source Link

The Department of Defense (DoD) is facing several unprecedented technological advances: Artificial intelligence applications and 5G already are transforming possibilities, and quantum computing is on the horizon. Each of these brings with it advantages as well as both first- and second-order risks. Harnessing innovation has been under the microscope, with special attention on innovation silos; however, analyses often focus solely internally (such as breaking down barriers between combatant commands1) or gaze solely outward (such as initiatives for implementing “a systematic and proactive approach with industry”2). Achieving success in this area is an organizational concern, but the responsibility and potential for it rest across the shoulders of every member. Because the human mind—as powerful as it is—is not singularly equipped to understand and address all of these developments and associated concerns simultaneously, the key to success lies in strategic, interpersonal collaboration.

A case that changed both technological and strategic options for the military sets the scene.

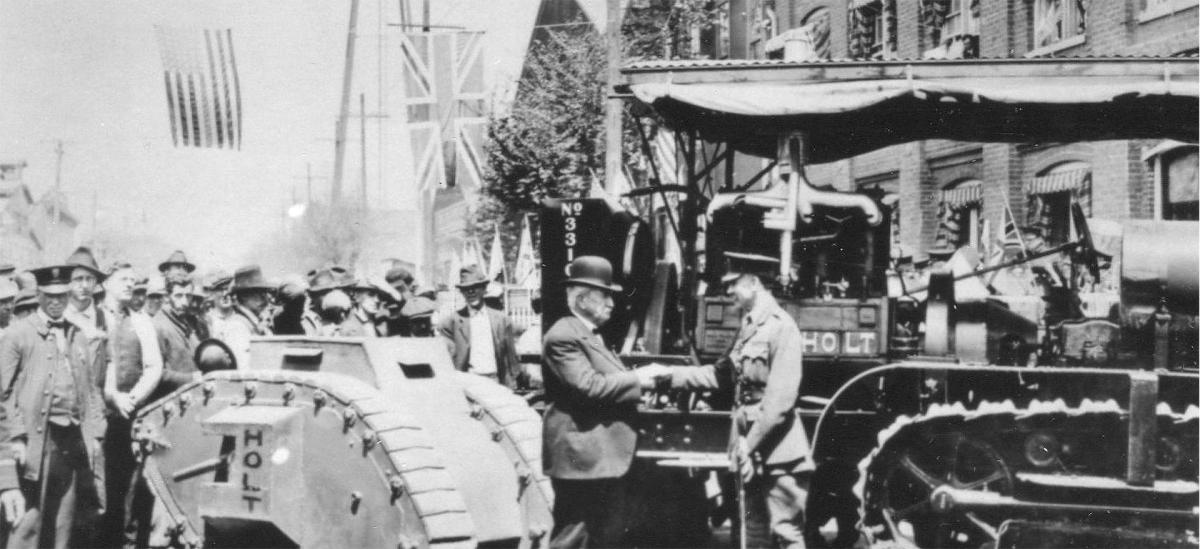

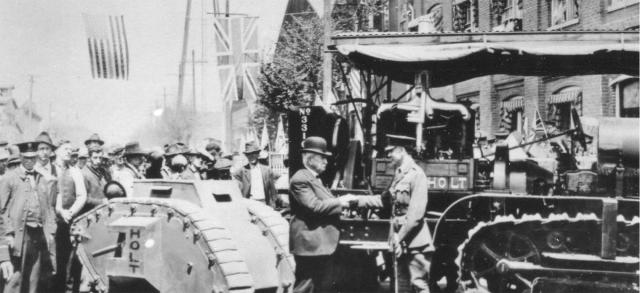

Humility in receiving ideas is integral to moving innovation forward. In April 1918, British General Ernest Swinton visited Benjamin Holt at his factory in Stockton, California, to thank him for his contribution to the equipment that helped win World War I, even though none of Holt’s original parts made it into the first tank. Credit: San Joaquin County Historical Society and Museum

The Tracked-Tractor

In 1883, Benjamin Holt moved to California to join his brothers and become mechanical lead in a wholesale hardware and wheel manufacturing enterprise.3 The business flourished at providing harvesting equipment near Stockton, California, but the weight of traditional harvesters proved problematic in the soft delta terrain near the San Joaquin River.4 Adaptations to the wheel design were necessary, and it was thus, in 1904, that the first Holt tracked-tractor was trialed.

Despite the innovation of Holt’s design, its mundane agricultural applications were far removed from any conceivable war-fighter concern; however, they were to prove pivotal to the military. While on show in Antwerp, Belgium, Holt’s design was spotted by mining engineer Hugh Marriott, who was in search of an inexpensive means to transport ore.5 Marriott grasped the potential military applications and wrote with excitement in 1914 to Ernest Swinton, a British colonel. Swinton brought the idea to the British War Office, eventually developing an armored, tracked fighting vehicle in 1916 that would become known as the “tank.”6 The same year, he commanded the first British tank unit at the Battle of the Somme.7

The inventor and the innovator are often conflated in literature, but the distinction between them is conversation—namely, that it requires collaboration to drive an idea to adoption. Personal conversations are a vehicle for pushing innovation forward.8 Nearly every step of tank development was dependent on individuals sensing a need and offering solutions to others through conversations.

DoD’s advantage in the current technological power competition likewise depends not only on invention and organizational strategy, but also on active and strategic conversation from each combatant in the collective cause. Next, let us take a closer look at the strategic selection of collaborators and the characteristic of an innovator that binds them together: determination.

Determination

The tank was inhumed in obstacles en route to adoption. Notably, Holt was not even the first to market a tracked vehicle design in Britain. British engineer David Roberts had recognized the military applications of tracked vehicles and demonstrated a prototype to the British military in 1907, without success, and later sold his own design patent to Holt.9 The enterprising Holt contacted the U.S. War Department regarding potential military applications in 1913 and again in 1914, when he offered to ship a tracked-tractor to any testing ground, free.10 The messages went ignored.

Later, in a parallel experience, Swinton faced opposition within the British government. He discussed the tracked-tractor with a friend from the Committee of Imperial Defence, and together they started a two-pronged political effort to lobby different departments. In response to their proposal, they received a note stating, “If the writer of the paper would descend from the realms of fancy to the regions of hard fact, a great deal of valuable time and labor would be saved.”11

If history were to follow a deductive path from this sequence, the tank should never have been invented. Yet, Swinton and Holt possessed an incessant intention to seize opportunities for discussion. This determination is psychological, sociological, and physical.

Psychologically, the innovator is constantly imagining and adapting their offer to the concerns of the environment (e.g., Holt’s offer of a free trial to allay risk aversion). Organizational policy and strategy hardly provide navigation through present technological shortcomings or obstacles to collaboration, nor is such imagination written into policy. It is a human ability. Even artificial intelligence cannot re-create this (as AI uses preexisting data). Imagining the preposterous potential of both invention and interpersonal collaboration is something only the human mind can do.

Sociologically, those same inconceivable ideas are likely to face belittlement, and the innovator must be determined to continue discussion when the opportunity arises. As with many modern innovations, the ideas underlying the tank faced derision on the road to success. A contemporary wrote that “Swinton knew only too well that G.H.Q did not believe in the Tank, regarding it as the mere toy of civilians at home.”12 Accusations of wasting “valuable time and labor” on “fancy” doubtless also hit the colonel hard.

Finally, the physical burden on the innovator cannot be dismissed. Opportunistic conversation is time-consuming, and since, unlike other tasks of physical endurance, the results may not be immediately apparent, it often is an unappreciated investment. Research has indicated conversation is bounded to four participants.13 Coined the “dinner party effect,” a discussion with more than four members will naturally fracture into smaller conversations, defeating the innovator’s ability to engage all participants at once. Thus, while large group meetings, conference presentations, and workshops can benefit information sharing, they are not conversations for innovation. Conversations pull from collective experience and intelligence and adapt dynamically—attributes not found in unidirectional communication. Consequently, building the interpersonal, two-way dialogue necessary for sensing and offering solutions (two innovation practices14) is a testament to the tenacity of the innovator.

Connectivity in Diversity

If anything is to be observed from the advent of the tank, it is that every opportunity for conversation should be seized. However, it would be negligent to dismiss the subject of collaboration without further consideration, especially with regard to strategy. Stepping out of a thought bunker necessitates gathering a variety of perspectives, including ones that might differ from the innovator’s own. Indeed, understanding the perspectives of those working on similar tasks, who have similar concerns, and who envision similar goals is not the challenging aspect of innovation. It is fairly easy to agree with like-minded individuals. But it is through outside insight and the type of counsel that challenges the innovator to think differently that a refined vision and leadership emerges.

This is not simply tolerance of different viewpoints nor necessarily an alteration of the innovator’s vision. Quite the contrary, it is about intentional construction of an interconnected web of insight on potential concerns and motivations. Even in the story of tank development, conversations spanned geolocations and fields of expertise: a farmer, a miner, and a soldier discussed mechanical engineering. One could mistake it for the start of a bad joke. Yet, if any one of these individuals had localized conversation to familiar and like-minded collaborators, World War I would have been very different. Connectivity among diverse perspectives is valuable to the innovator—both then and now.

Separately and unbeknownst to Swinton, Lieutenant Albert Stern—a banker by background whose physical injuries originally prevented him from volunteering in the Royal Naval Reserve—also was discussing land transport options for the British Army. Stern had a proclivity for seizing conversational opportunities. At a dinner party in early 1915, he presented First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill with the concept of a giant tricycle with 40-foot wheels as a weapon of war for crossing the Rhine.15 Stern was earnest in his proposal, and the carefully planned tricycle came complete with three turrets for guns, horsepower specifications, and three-inch armament. The idea was not exactly well received by his military colleagues.

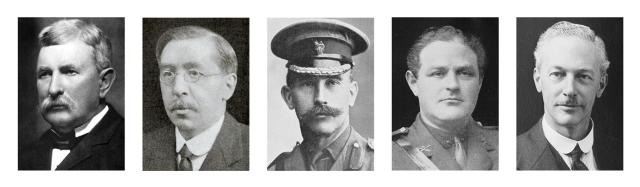

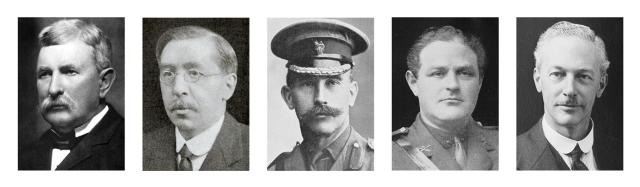

Stepping out of a thought bunker necessitates gathering a variety of perspectives, including ones that might differ from the innovator’s own. In the story of tank development, conversations spanned multiple fields of expertise: a farmer (Benjamin Holt), a miner (Hugh Marriott), a soldier (Ernest Swinton), a banker (Albert Stern), and a naval architect (Eustance d’Eyncourt). Credit: Library of Congress

Churchill, however, ordered a new Landship Committee be set up and asked Stern to be its secretary. Within the committee, Stern met Director of Naval Construction Eustance d’Eyncourt, who was unreservedly applying his ship-design expertise to brazen ideas of large and fast submarines (six of his designs sank and one disappeared).16 Thus, the already eclectic collection of individuals involved in the story is expanded: a farmer, a miner, a soldier, a naval architect, and a banker with an absurdly active imagination.

Metacognitive awareness facilitates detection of potential fallacies in the perceived variety and range of conversation partners. It essentially provides a “stagnancy assessment” of the conversation pool. From such an assessment of the collaboration pool on a given subject, the innovator can identify facets of experience they have not yet tapped into. Stagnancy is the operative word here. There is no reason to abandon established partnerships; however, discussing subjects cyclically with the same array of people creates conceptual inbreeding.17 Ironically, there is thus a cognitive dissonance in innovation initiatives that are based strictly and solely on established internal DoD and industry partners. If “insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” (a quote often misattributed to Einstein), then a rational innovator will consciously assess the variety of their information sources and conversation partners on specific topics and adapt accordingly.

Both the innovator and their conversation partners are individuals; thus, integrating insights from a diversity of perspectives and experiences also includes making new connections within established organizational partnerships, as well as new connections outside them. Indeed, it would be naïve to assume that simply conversing with people from a “new” organization is sufficient or even a correct approach. What, then, is the correct approach?

Recall that the innovator’s aim is to pull from a variety of experiences and insights that they do not possess themselves. Ergo, by first identifying the innovator’s own viewpoint, environment, and experience-based community, it is possible to strategically reach beyond it.

There is a military culture. There is an industry culture. There is a USS Mount Whitney culture, an IBM culture, and a software developer culture. These often are referred to as microcultures. Microcultures also arise around upbringing, race, gender, and geographical locations—even favorite lunch locations.18 Microcultural differences are spoors of a prize worth pursuing. By seeking out collaborators from other microcultures, the innovator avoids niche solutions and conversations. Intercultural (mis)communication can be a daunting prospect, and a budding innovator could be forgiven for retreating back to a bunker of familiar faces, known contacts, and a favorite lunch corner to dodge it. From in-jokes and establishing rapport to building respect and credibility, cultural nuances affect communication. Overcoming this trepidation is yet another facet of the determination character trait.

July 1915: The rebuffed Swinton heard of the Landship Committee and arranged to meet with Stern. Swinton is documented as having said, “The Director of Naval Construction appears to be making land battleships for the Army, who have never asked for them, and are doing nothing to help. You have nothing but naval ratings doing all your work. What on earth are you? Are you a mechanic or a chauffeur?” “A banker,” Stern responded.19

There was a stark variety of microcultural backgrounds among Swinton, Stern, and d’Eyncourt. Yet, this amalgamation of perspectives was a turning point in the development of the tank. Barely six months later, the tank, as we know it, was trialed.20

Assuming that the “right people” to have conversations with are only those in positions of authority within one’s own organizational branch would be erroneous. If knowledge is power, then power lies not with a specific position, but in the variety of connected perspectives that can be aggregated. Investing in human capital is therefore not only a Navy strategic goal for the organization, but also a strategic goal for the individual innovator.

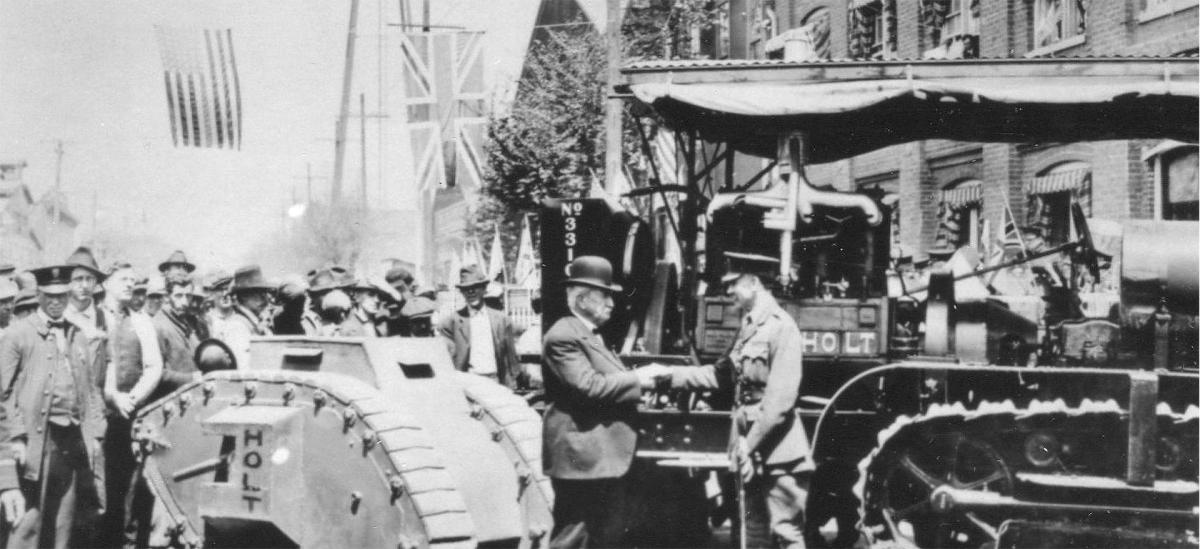

A Mark 1 tank heads into battle on the Somme in 1916. Credit: Alamy

Trust and Humility

Trust is vital to overcoming microcultural differences and bridging potential miscommunication. It opens the door to both sharing and receiving new ideas and is entwined with respect. Consequently, trust is one of the most critical cornerstones of collaboration. Yet, trust is fragile and susceptible to an innovator’s suppositions.

Inherent to microcultures is a strong group-internal trust, and this bleeds into competency assessments about those outside the microcultural trust circle.21 Unsurprisingly, people react most positively to a potential collaborator who is perceived as both competent and warm.22 However, there are also two potential and less favorable perceptions: warm but incompetent (“paternalistic prejudice”) and not warm but competent (“envious prejudice”).23 Research indicates that people of a different microculture (out-group partners) are more generally perceived from “paternalistic prejudice” or “envious prejudice” standpoints.24 Thus, the sociological fabric actually pushes the innovator away from assembling more insight and back into their own innovation bunker—they are pushed away from innovation.

This subliminal sociological effect undermines perception of out-group competency for a given task and might affect collaboration between communities of practice, e.g. military-civilian, Navy-Army, etc. While awareness on both sides facilitates the best discourse, it is the innovator who must calibrate against the obstacle. Conscious assessment of assumptions and trust, and an intentional traverse of them, paves the way to initiating dialogue.

In 1912, three years before Swinton’s chanced introduction to Stern, Australian engineer Lancelot de Mole had submitted plans for an armored tracked vehicle to the British War Office. Mole’s carefully drawn plans were ignored and placed in the office archives, unknown even to the others later involved in Swinton’s efforts.25 Such dismissive attitudes toward discussion and assumptions on irrelevancy were the trademark of every failed progression attempt in the history of tank development.

In contrast, when Major Walter Wilson met Stern in July 1915 and was given the option of working on the tracked vehicle design with either a Colonel Crampton or industry partner William Tritton of the Foster Company, he asked for the latter. Wilson’s interest in expanding outside his military innovation microculture may seem surprising (particularly since Crampton had worked heavily on similar vehicle designs himself), but he was quoted saying that working together with Tritton, “We would soon produce a machine that could do something.”26

Tritton, a businessman, likewise trusted Stern and Wilson, devoting extensive efforts to the collaboration at a time when raw materials were scarce, designs were speculative, shareholders expected a return, and the Foster Company had just begun to show decent business stability. Furthermore, among the Army colleagues of the Landship Committee, it was naval officer d’Eyncourt who finally solved the problem of where guns should be mounted on the new army land vehicle, pulling from his naval background, where guns with swivel capabilities were mounted on ship sides.27

These examples of intentional, collaborative, and active trust in a diversity of backgrounds and experiences permeate the history of the tank.

It would be remiss to conclude without noting the entwinement of trust in out-group competency and humility in receiving ideas and relinquishing control. Tanks were still science fiction in 1903, when novelist H. G. Wells wrote a magazine story, “The Land Ironclads,” about armored tracked vehicles fighting battles—an idea Stern credited for inspiration.28 Every British tank during the Kaiser’s War was based on the designs of d’Eyncourt, Tritton, and Wilson, and none of Holt’s original caterpillar vehicle parts made it into the first tank. However, after the Battle of the Somme and prior to the end of World War I, Swinton traveled to Stockton to personally thank Holt for his contribution.29 Swinton in turn is often given credit for the tank, even as far as claims that he drafted the design himself.30 Yet, by Stern’s firsthand evaluation, the naval architect d’Eyncourt was “the tank’s true father.”31 What is certain is that this group of innovators had the humility to hunt for true technological dominance by pulling from a diversity of expertise. They trusted each other’s experience—often far different from their own—and had the humility to do so.

Stepping Out of the Bunker

Terminology builds mind-sets and vision, and substandard mental imagery leads to substandard course correction. Within innovation, this is particularly true. The “innovation silo” imagery is outdated and misconstrued.

Silos are not problematic in the physical world; they serve precisely the same long-term storage purpose that they were first built for hundreds of years ago. Innovation, in contrast, is active, interpersonal, and requires stepping beyond familiar, microcultural walls. It has always been this way. Although collaborators who share experiences similar to the innovator’s own—those who are in the same innovation bunker—are valuable resources, sole reliance on such assets results in a conceptual trap.

It is daunting to step out of the innovation bunker, but through such action collaborative expertise and situational perspective are gained and forward progression made possible. We do not hold a static technological line. The surge in technological innovation requires advancement into unfamiliar territory alongside potential allies who may be entrenched in their own innovation cells, as the history of the tank illustrates. It is an undertaking worthy of resolute commitment. And shying away from such innovation challenges? That would be bunkers.

No comments:

Post a Comment