Eliot A. Cohen

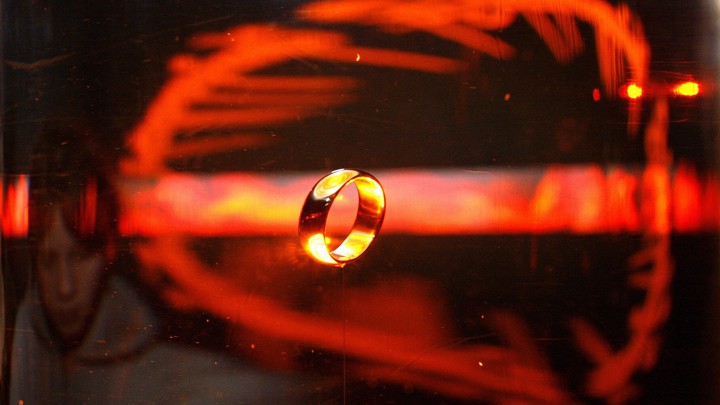

Conservatives in distress turn to ancient texts. In the current circumstance, those of us of a Hebraic cast reach for the prophet Isaiah in his darker moods, or the even fiercer denunciations of Amos. Devout Christians despairing of a society in full malodorous rot look to The Rule of St. Benedict. Classicists might pick up a volume of Seneca, sighing wistfully as they contemplate the philosopher’s fate at the hands of his mad pupil, Emperor Nero, who, unlike President Donald Trump, at least played a musical instrument competently. A more twisted few will reach for Machiavelli. For those undergoing real tests of the soul, however, the place to go is J. R. R. Tolkien’s modern epic, The Lord of the Rings.

Conservatives in distress turn to ancient texts. In the current circumstance, those of us of a Hebraic cast reach for the prophet Isaiah in his darker moods, or the even fiercer denunciations of Amos. Devout Christians despairing of a society in full malodorous rot look to The Rule of St. Benedict. Classicists might pick up a volume of Seneca, sighing wistfully as they contemplate the philosopher’s fate at the hands of his mad pupil, Emperor Nero, who, unlike President Donald Trump, at least played a musical instrument competently. A more twisted few will reach for Machiavelli. For those undergoing real tests of the soul, however, the place to go is J. R. R. Tolkien’s modern epic, The Lord of the Rings.

This thought is triggered by a recent column by Ross Douthat, one of the small-but-doughty band of conservatives ensconced in a safe space in the high tower of The New York Times. After dismissing some of those conservatives he no longer agrees with as “converts and apostates,” he urges his readers to turn instead to those “thinkers and writers who basically accept the populist turn, and whose goal is to supply coherence and intellectual ballast, to purge populism of its bigotries and inject good policy instead.”

It is a more measured version of a larger phenomenon: erstwhile NeverTrumpers who wryly describe themselves as “OccasionalTrumpers,” or who attempt to cleanse themselves of the stain of having signed letters denouncing candidate Trump by praising President Trump’s achievements and his crudely framed, rough-hewn wisdom, deploring his language but applauding at least some of his deeds. It is the temptation to accommodate oneself to the nature of the times, as Machiavelli would have put it, and to ally—cautiously but definitely—with the Power that is rather than the principles that were.

And that is where Tolkien comes in. His masterwork—the six books in three volumes, not the movies with their unfortunate elisions, occasional campiness and spectacular computer-generated images—addresses many themes relevant to our age, not least of which is that temptation.

At the beginning of Book II, elves, men, and dwarfs have gathered at Rivendell, home of Lord Elrond. There they debate what to do about the ring of the Dark Lord, Sauron, which has by a curious chance fallen into the possession of the hobbit Frodo. Toward the end of their deliberations they hear a report from Gandalf, the wizard who had befriended Frodo, and who had been taken prisoner by Saruman, the most senior wizard of his order, and escaped. Saruman had learned that the Ring had fallen into the possession of the hobbit, and he wanted Gandalf to help him get it. Gandalf reports Saruman’s pitch as follows.

“A new Power is rising. Against it the old allies and policies will not avail us at all. There is no hope left in Elves or dying Númenor. This then is one choice before you, before us. We may join with that Power. It would be wise, Gandalf. There is hope that way. Its victory is at hand; and there will be rich reward for those that aided it. As the Power grows, its proved friends will also grow; and the Wise, such as you and I, may with patience come at last to direct its courses, to control it. We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order; all the things that we have so far striven in vain to accomplish, hindered rather than helped by our weak or idle friends. There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means.”

And there you have it. Ally with the rising power (Sauron is making his ashen, desolate homeland, Mordor, great again) and use your wisdom to contain and guide it. Your old friends and allies are fools or weaklings. Go along with the inevitable, and you may shape the new world; oppose it, and you will simply fail and perish.

Gandalf does not fall into the Saruman trap. He knows, for one thing, that only one hand at a time can wield the ring, but more important, he knows—for Frodo has already offered the Ring to him—that the temptation to do good would get the better of him. It would start well and end ill, because the power of the Ring is corrupt. Later on in the book, the elven queen Galadriel similarly rejects Frodo’s desperate offer to rid himself of his burden for the same reason. Both Gandalf and Galadriel cannot be sure that the alternative course—have Frodo attempt to destroy the Ring by hurling it into a volcano—will succeed. In fact, they know that the overwhelming odds are that it will fail, with ghastly consequences. And they know that even if that desperate venture succeeds, it means the end of the world they have known, and their own permanent exile from Middle Earth. And they accept both possibilities.

Saruman, on the other hand, goes from bad to worse. He eats himself out with ambition, he commits extraordinary cruelties, and he ends up a mean, twisted, and impotent refugee whose lone follower loathes him. His infatuation with power has ruined a being once wise and beneficent.

The temptation of intellectuals is often this: the urge to influence the mighty because they lack the skills or the lineage or the luck to rule themselves. At the moment, despite all the investigations and scandals, the stumbles and desertions, Trump and the political party that has succumbed to his bullying and his appeal look like power, at least if you are a conservative thinker. And after several generations of conservative intellectuals coming to think that their job is to shape policy rather than simply articulate truth and outline the consequences of decisions or actions, a future of permanent exile from influence looks unacceptably bleak.

The stakes are not nearly as high for conservative thinkers as they were for the inhabitants of Middle Earth, but the basic idea is worth pondering. Some of them wish to walk back their condemnation of Trump, the animosities that he magnifies and upon which he feeds, the prejudices upon which he plays and the norms he delightedly subverts. They do so not because their original judgments have been proved unjust—far from it—but because, weary of unyielding opposition, they would like to shape things, or at least to hold communion with those who are in the room where the deals are done. But as Gandalf and Galadriel could teach them, the height of wisdom is to fear their own drive for power, to fight the fight in a darkening world even if it looks likely to end in failure, and, above all, to choose to remain their better selves.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment