Antonia Colibasanu

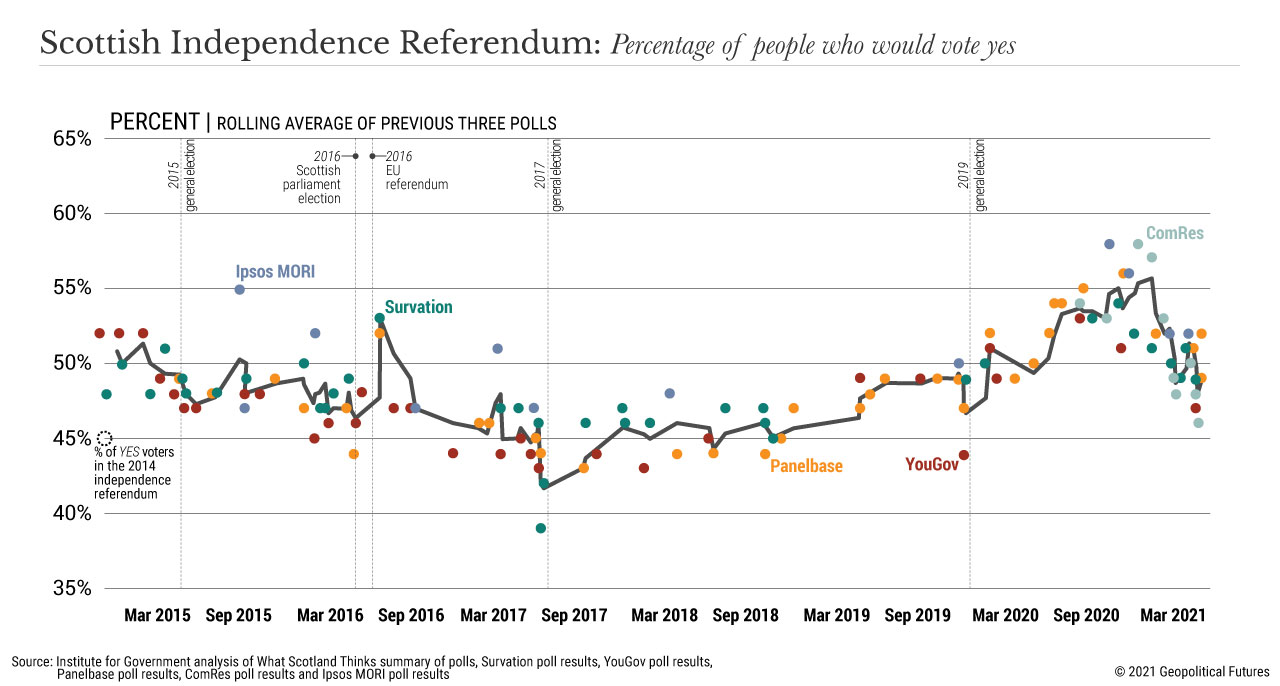

This week, the conservative Sunday Times newspaper published the results of a poll showing that support for Scottish independence has dropped to its lowest level in two years. It’s not surprising, considering that since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the issue of independence has come second to more urgent problems that need to be addressed. However, in May, when the pro-independence Scottish National Party and the Green Party won a collective majority in Scottish parliamentary elections, the possibility of holding another independence referendum was put back on the agenda.

Since 2016, the independence debate has been tied to Scotland’s rejection of the U.K.’s withdrawal from the European Union. Last week, a report released by the Scottish government about Brexit’s impact on Scotland concluded: “Brexit is having a tangible and harmful impact on the quality of life of the people of Scotland and on Scottish businesses.” It seems that the Scottish government isn’t done making its case for independence. But it’s also redefining its priorities as it grapples with a number of more urgent challenges. The current calls for independence should therefore be seen less as a real push for sovereignty and more as political bargaining with London. After all, Scotland understands full well that the Commonwealth is critical for London – perhaps now more than ever.

Scotland’s View of the Union

Scotland entered a voluntary union with England in 1707. But since the end of World War II and the collapse of the British Empire, Scotland has grown increasingly anxious about its place in it.

There are three historical concepts that explain Scotland’s view of the United Kingdom. The first is unionism. Since the late 18th century, unionists have argued that Scotland is better off in a union with England than on its own. They supported the merger of the United Kingdom’s constituent parts – England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – and the establishment of a unitary parliament at Westminster.

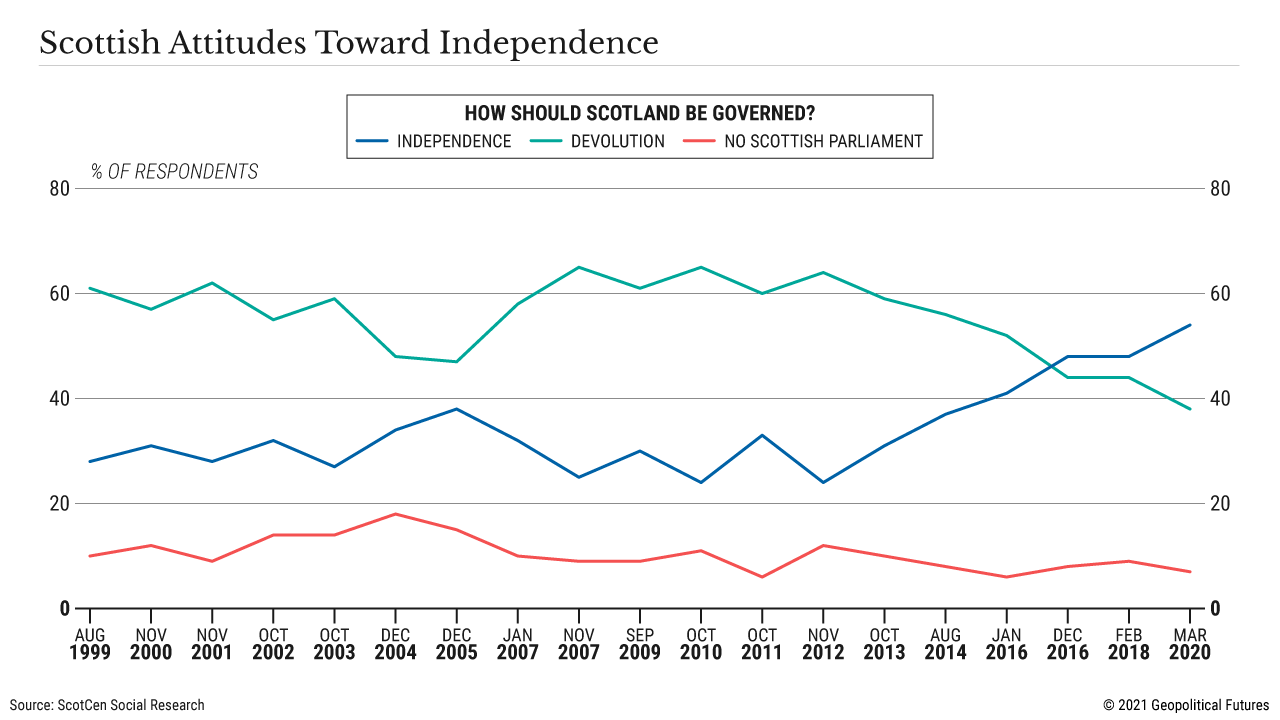

The second concept is devolution, also referred to as “home rule.” It emerged in Scotland in the late 19th century, when the Scottish Liberal Party adopted the demands of the Irish home rule movement. Under a devolved system, the U.K.’s constituent parts would be given authority over certain areas of governance. In Scotland, devolution has enjoyed wide public support since the 1960s, when calls for more autonomy grew.

The third concept is independence – i.e., the creation of a separate Scottish state. Its rise coincided with the fall of the British Empire. So long as the empire remained intact, Scotland was able to preserve its unique identity and traditions. It didn’t fear being overtaken by England because the empire was big and global enough to allow room for multiple entities, each of which was distinct from the others. With the empire’s collapse, however, Scotland feared that the interests of England, which had a substantially larger population, would dominate the union.

However, independence wasn’t a serious option until the 1970s, when the Scottish National Party gained popularity in the polls. Many independence supporters promoted a moderate vision of independence – within the broader framework of the Commonwealth and the European Union (before Brexit) – and did not necessarily support complete secession. At the same time, however, two factions developed within the SNP: the fundamentalists, who want full independence immediately, and the gradualists, who support increased devolution and are open to negotiations with the unionists.

As the independence movement gained momentum, London had no choice but to listen to the demands for more autonomy. In 1997, Scotland held a referendum on devolution that resulted in a vote in favor of establishing a Scottish parliament. The parliament was founded in 1999 and granted extensive and exclusive powers over a range of domestic policy issues, though it lacked authority over critical fiscal matters including welfare benefits.

Drive for Independence

Scottish elections use a modified system of proportional representation where people cast two votes: one for a representative for their constituency and another for a political party. The representatives for the second vote are allocated based on their party’s share of the overall vote. This system makes it difficult for any one party to gain a majority and often requires parties to build coalitions in order to form a government. After the 1999 and 2003 parliamentary elections, for example, no party won enough seats to establish a majority, so Labour and the Liberal Democrats joined forces to form a government.

In 2007, the SNP won one more seat than Labour and decided to form a minority government. The SNP had promised to hold an independence referendum but was unable to secure majority support in the Scottish Parliament for its plan. In response to the SNP’s independence push, the unionist parties in Westminster – Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats – pushed through modest increases in Scotland’s fiscal powers.

In 2011, the SNP won an absolute majority. It used its newfound power in parliament to press for its independence plans. Notably, however, support for independence was lower in 2007 and 2011 than it had been a decade prior. During this time, support for independence hovered at between 20 percent and 25 percent, after rising to 30 percent in the late 1990s when the Conservative Party held power in the British Parliament. It seems, therefore, that the SNP’s victory was a result not necessarily of its support for independence but of the public perception that it could form a competent government able to make decisions on its own without requiring Westminster’s approval.

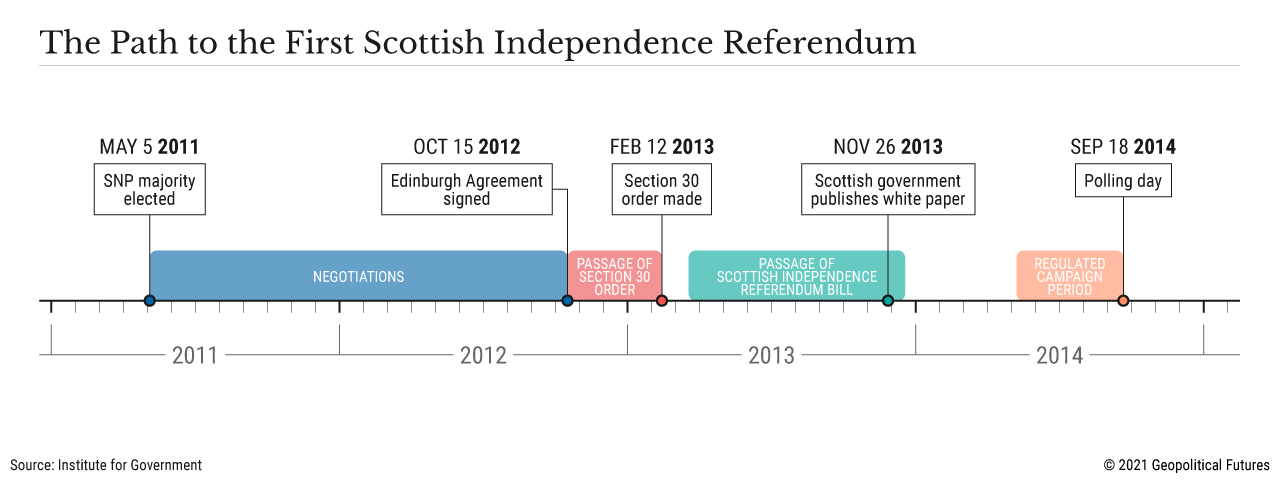

The low rates of support for independence were a big part of the reason the unionist parties and, ultimately, London agreed to hold an independence referendum in 2014. They believed the pro-unionist side would win a decisive victory. Under the 2012 Edinburgh Agreement, the Scottish Parliament was granted the power to hold such a vote, but under certain conditions. The referendum would ask only one question, which should be clear and present a choice between independence and union, with no option for enhanced devolution.

By the final week of the campaign, the “no” side’s 20 percent advantage in polls had disappeared, and the two camps were neck and neck. Some polls even gave a slight edge to the “yes” campaign in the days leading up to the vote. That’s when London stepped in. Former Prime Minister Gordon Brown persuaded the unionist parties to promise the public that if the “no” side won, the Scottish Parliament would be granted new powers over domestic policy – including fiscal authority and some power over welfare payments.

The “no” camp’s victory ushered in a system of enhanced devolution, also known as devolution max (or devo-max). Although the unionists prevailed, they were forced into a compromise they wanted to avoid. The vote was therefore essentially a political victory for the “yes” campaign.

The referendum buried the issue of independence for a while, but it also radically altered politics in Scotland and Scotland’s relationship with the union. Though the SNP was the head of the government at the time, it managed to run an anti-establishment campaign, leading the charge to pull Scotland out of a union it had been part of for centuries. After the Brexit referendum, in which the majority of Scots voted to remain in the EU, the issue of Scottish independence reemerged. It’s been used as a political tool not only to get votes but also to keep London engaged.

Priorities and Context

In parliamentary elections in early May, the SNP won its fourth consecutive victory. Its governing coalition – which also includes the Greens – controls 55.8 percent of seats in parliament. However, several hurdles remain in its quest for Scottish independence.

Although Section 30 of the 1998 Scotland Act enables the Scottish Parliament to pass legislation on issues that are traditionally under Westminster’s jurisdiction, including holding an independence referendum, the U.K. prime minister must first approve the step. Immediately after the SNP’s victory was announced last month, Prime Minister Boris Johnson called for talks with the leaders of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales but made it clear he was against the idea of another referendum.

Another obstacle is deciding what independence for Scotland would actually look like. After the 2014 referendum, Scottish society became even more politicized. The poll triggered conversations over systems of governance, self-determination and policymaking. New social movements emerged, including some with strong nationalist tendencies. The government now needs to present the public with a clear plan for a future independent Scotland. It’s not an easy task, not only because the SNP needs to negotiate its vision with the Greens but also because it needs to take into consideration the new realities of the pandemic.

Scotland’s economic future is also a concern. The Brexit report that the Scottish government published last week indicates that Scotland’s trade with the EU has declined over the past five years, especially for certain sectors. It also states that Scotland’s population dynamics are very different from those of the U.K., arguing that Scotland needs to maintain immigration from continental Europe to support economic growth. The socio-economic consequences of the pandemic were mostly left out of the report, except for its impact on worker migration. Foreign policy was also mostly omitted, though the report mentions the free trade agreement between the U.K. and Australia, which many believe will be disadvantageous for Scottish farmers.

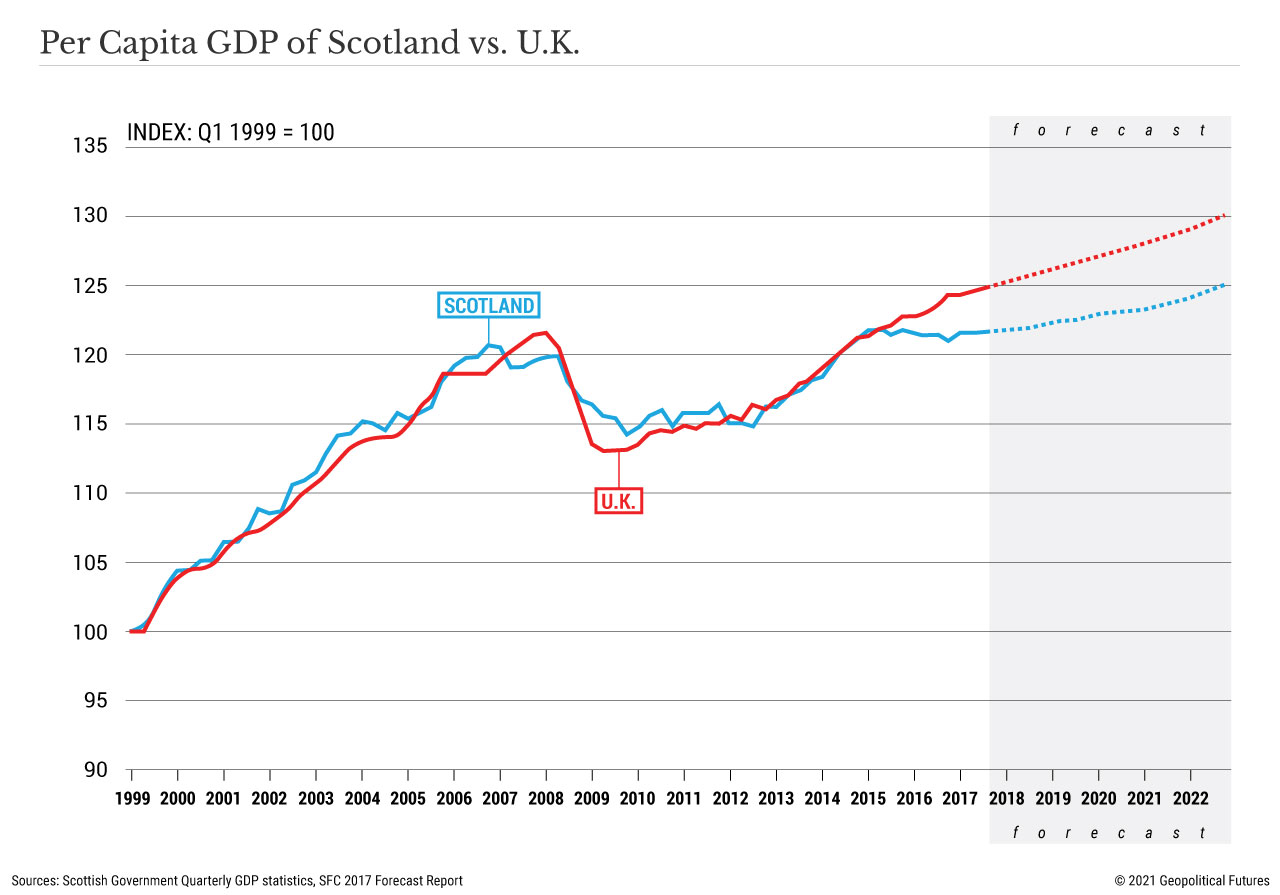

Scotland’s gross domestic product per capita is 97 percent of the British average. During the 2014 referendum campaign, some argued that Britain was economically benefiting from Scotland, for example by collecting most of the revenue from oil reserves in Scottish waters. For the most part, however, Scotland is heavily dependent on Britain economically – even more so than it is on the EU. Most of its goods and services are sold within the U.K., and both the Royal Bank of Scotland and the Bank of Scotland have been owned by the U.K. government since the 2008 crisis.

For Scotland, the economic links to Britain are so deep that, during the 2014 referendum campaign, the pro-independence camp wanted Scotland to remain part of a monetary union with the rest of the U.K. If an agreement on monetary union could not be reached, Scotland would still have used the British pound – a better alternative, it was thought, to switching to the euro or developing its own national currency.

The Strategic Questions

Although it is pro-European, Scotland knows reentry won’t be easy. It would be several years after a positive independence vote before Scotland would separate from the U.K., and then several more years before it could achieve all the benchmarks needed to join the EU. To accede, Scotland would then require the unanimous support of all 27 EU member states.

The pro-independence camp promises an accelerated path to re-accession, given Scotland’s past association with the EU, but the bloc’s internal politics muddy the waters. Moreover, the independence process would be monitored closely by EU states with their own separatist tendencies, like Spain’s Catalonia region, and those states would have an incentive to raise the cost of independence by making EU membership difficult.

The other strategic question the Scottish government needs to plan for is Scotland’s defense and security. During the 2014 referendum campaign, the SNP said Scotland would seek NATO accession. As with joining the EU, states must meet benchmarks and secure unanimous backing to join NATO. And some NATO states could similarly see Scotland’s independence as a dangerous precedent and resist its accession.

But NATO, though it’s increasingly a political alliance as much as a military one, still counts on the U.K. as one of its most important members. The U.K. is second only to the U.S. when it comes to contributing alliance capabilities, and it is an important supporter of U.S. strategy worldwide. More important, the security climate in 2021 is very different from 2014. Nuclear arms control is a bigger issue, especially since the U.S. decision in 2019 to withdraw from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Britain’s Trident nuclear deterrent is based entirely in Scotland, but the SNP said during the 2014 referendum campaign that Scotland should be nuclear-free, which means that in theory the weapons would be withdrawn if Scottish voters opted for independence. In that case, there would be little Scotland could offer NATO.

Scottish independence would be far more complex today than in 2014. The EU is too preoccupied with its own problems to help Scotland fight off the immediate economic problems caused by the pandemic. London, on the other hand, has a strategic incentive to keep the union intact and an imperative to increase its global role independent of Europe – which would suit Scotland just fine.

Immediately after Brexit, Scotland feared it may no longer be able to maintain its distinctiveness and political power in a union that prioritizes parochial interests (and, worse, English interests) over global concerns. Five years later, the Scottish government’s report meant to criticize London’s handling of Brexit discussed the impact of a recently agreed free trade deal between the U.K. and Australia. Scotland will continue to monitor the effects of Brexit on its economy, while promoting the idea of an independence vote. This provides Edinburgh with the best of both worlds – the benefits of union, combined with leverage in negotiations about its own position within the U.K.

No comments:

Post a Comment