Sara Z. Kutchesfahani, Tom Weis

Mexican artist Pedro Reyes constructed a three-story inflatable mushroom cloud, Amnesia Atomica, to “put pressure on political leaders, policymakers, and global citizens by reminding them of the consequences of inaction.” Similarly, American artist Barbara Donachy installed 35,000 small clay missile replicas in her exhibit, Amber Waves of Grain, to depict the volume of the US nuclear arsenal. And Smriti Keshari and Eric Schlosser created The Bomb—a multimedia experience that immerses “the viewer within the story of nuclear weapons.” Even this publication relies on design when it presents the Doomsday Clock as a visual representation of “how close we are to destroying our world with dangerous technologies of our own making.”

Members of the public, policymakers, and scientists would be wise to look to artists, designers, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations that have successfully experimented with creative approaches to raising public awareness about nuclear risk.

One of us—Tom—teaches industrial design at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he helps students leverage design techniques on the topic of nuclear threats. One of Tom’s students, for example, designed a game that allows players to advance through virtual worlds while learning nuclear facts. Another student wrote a hip-hop song, “Forget what you know,” that considers what a nuclear winter might look like:

Do you see our future?

And if so, is there a chance of rain?

Do the clouds promise pain? Is the landscape unchanged?

Or should we keep our heads low, eyes closed, and pray in vain?

Over the past five years, Rhode Island School of Design students have been increasingly interested in design courses focused on security. And many students continue security-focused design work after graduation. For example, two recent graduates were selected as Global Security Design Fellows, a program that is funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

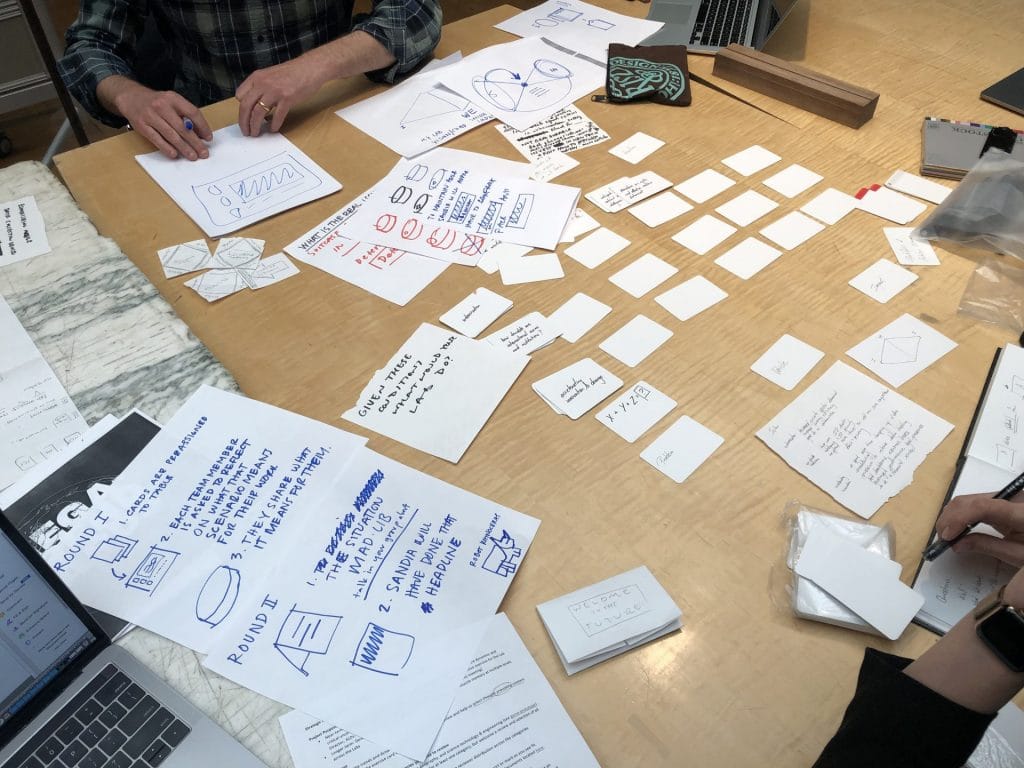

West Point cadets and Rhode Island School of Design industrial design students discussing the future of conflict in urban environments. Credit: Tom Weis. Used with permission.

West Point cadets and Rhode Island School of Design industrial design students discussing the future of conflict in urban environments. Credit: Tom Weis. Used with permission.Tom has also worked on a nuclear-themed design project at Sandia National Laboratories. In a 90-minute exercise, he invited senior lab leaders to select one card from each of three trend categories: science and technology, the world order, and human geography. They were then asked to imagine a scenario in which the trends collided, after which they discussed how they might have anticipated and adapted to the scenario as individuals, a lab, and a nation. For example, in one imagined scenario from an outside expert, a lack of fresh water accelerated the construction of small nuclear reactors in the region, which in turn outpaced agencies’ abilities to monitor the reactors. Participants were encouraged to reframe questions and expand upon the narrative as they sought creative solutions. The Carnegie Corporation of New York saw value in this work and subsequently provided funding for a digital version of this activity to reach a wider audience.

The International Atomic Energy Agency has also demonstrated a willingness to try design methods as it works to address challenges in the nuclear field. In its 2020 Emerging Technologies Workshop, they enlisted designer Marco Steinberg to give the keynote. Steinberg shared insight from his design practice, including his view that innovation often relies less on new technology than on organizational change. The workshop sessions encouraged generative discussions that are deeply rooted in design practices. In one workshop, participants reconfigured their seating arrangement from one in which participants were all looking toward the front of the room to one in which they gathered in small groups—an arrangement that facilitated collective brainstorming. It was exciting to transform a space designed for lectures into one that fostered active work among participants.

In another design-meets-nuclear example, the N Square Fellows’ Voices in Action campaign offers policy analysts models for improved work cultures, professional development opportunities, and leadership and mentorship opportunities. The models offer a mix of formal and informal, structured and unstructured, and internal- and external-facing ways to acknowledge, amplify, celebrate, and challenge nuclear policy experts. The celebration model, for example, champions large successes such as individuals’ publications and media appearances as well as small successes such as an unusually quiet colleague who speaks up and ensures that they are heard. The models were designed to be flexible and adaptive, as a diversity of perspectives are needed to address problems.

When people pursue art and design projects, they are asked to observe, practice, listen, and ask questions without fear. This requires a mix of humility and bravery. But when the best practices of art and design are in place, participants can expect direct, specific, constructive, and collaborative feedback that encourages them to act—and get results. Members of the public, policymakers, and scientists concerned about nuclear threats might take note. To address the existential threat that nuclear weapons pose to humanity, the world may need a creative solution.

Xi Jinping is displayed on a screen as Chinese battle tanks roll across during a parade in Beijing in September 2015; the military guarantees the Communist Party's ability to hold onto power. © AP

Xi Jinping is displayed on a screen as Chinese battle tanks roll across during a parade in Beijing in September 2015; the military guarantees the Communist Party's ability to hold onto power. © AP