By Simon Sharwood

Black Hat Asia The USA, China and Russia are doing all that they can to avoid development of a treaty that would make it hard for them to conduct cyber-war, but an effort led by the governments of The Netherlands, France and Singapore, together with Microsoft and The Internet Society, is using diplomacy to find another way to stop state-sponsored online warfare. The group making the diplomatic push is called the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace (GCSC). One of the group’s motivations is that state-sponsored attacks nearly always have commercial and/or human consequences well beyond their intended targets.

As explained today in a keynote at Black Hat Asia by GCSC commissioner and executive director of Packet Clearing House Bill Woodcock, those behind state-sponsored attacks are usually either hopelessly optimistic, or indifferent, to the notion that their exploits will be re-used. The results of that faulty thinking are history: the likes of Stuxnet, Flame, Petya and NotPetya did huge damage well beyond their intended targets, imposing massive costs on businesses.

Cyber attacks ignore the laws of war

Woodcock also said that nations’ acceptance of collateral damage from cyber attacks flies in the face of established conventions of war.In what he called a conventional “kinetic war”, governments mostly attack military targets. If they attack civilian targets like hospitals or schools, swift condemnation follows.

But malware attacks civilian infrastructure indiscriminately, making cyber-weapons radically different to conventional weapons.

Governments know their malware attacks such targets, but can hide behind the difficulty of attributing attack sources to deny their actions.

“Where that leaves us is having to spend a lot to money to defend ourselves,” Woodcock said, describing his role at the Clearing House, which operates internet exchanges, provides DNS services and consults in internet regulation. Woodcock helped to develop some basic elements of the DNS. He is therefore rather testy that money the Clearing House spends on security “… is not going on making the internet faster, bigger or better, or more available to more people.”

“So the networks that I run, because we have a lot of critical infrastructure on them, we have to try to defend against as much of this stuff as we can. And so we have to overbuild a thousand to one.”

Users of all sizes have different investment ratios, but Woodock said they are still “over-investing, maybe five to one, maybe ten to one. But it is all money they could be putting into other things.”

And ironically, businesses that have to over-invest in security to defend against state-sourced attacks paid for the development of those attacks with their taxes.

“For us at one thousand to one, we could be providing services in one thousand extra locations. We could provide nameservers in a thousand times more cities. We could be providing service faster, to more people, addressing the digital divide more successfully. But instead we are having to build things way, way bigger than we need to provide the actual service.”

Woodcock said that nations capable of conducting significant aggressive cyber-ops don’t really care about the collateral damage they cause and also don’t want their capabilities regulated. They therefore enter into essentially meaningless pacts or give lip service to development of binding treaties.

Enter the GCSC, which he explained to The Register hopes to create “norms” for online warfare and have a critical mass of nations adopt them so that countries that don’t play by the rules are easily-identified as rogues.

“We are not seeking unanimity, but instead something more like the consensus we operate the internet on,” he said. Woodcock also said he fancies the diplomatic effort is internet-like in that it plans to route around troublesome members of the global system.

GCSC is currently working on two things: a definition of an online non-aggression pact, and; a definition of what should not be attacked in a cyber-war.

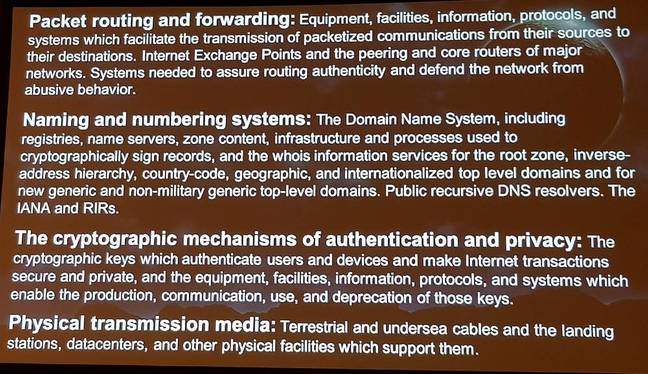

Progress is slow, Woodcock said, because diplomacy moves slowly. But the group recently agreed on the wording “public core of the internet” to describe the online resources that should be out of bounds for state-conducted cyber-attacks. He’s pleased that term is so vague, as it means a fresh and useful definition can be created. A recent GCSC meeting, he said, saw he and other technical experts squeeze in a discussion of how to expand the definition with the following result.

Public core of the internet draft definition from the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace. Click the image to enlarge

Woodcock told The Register the GCSC is one year into a three-year program and he is encouraged by progress. His hope is that if the body can agree on norms, and enough nations agree to them, that nations who don’t climb aboard feel diplomatic pressure to come into line or suffer sanctions for not having done so.

And perhaps, one day, that pressure will be enough that offensive cyber ops either stop, or at the very least become less harmful to businesses and civilians – and the parts of the internet on which they rely. ®

No comments:

Post a Comment