The minds of children need room to breathe, to be inspired by vision, and the health-bringing balm of many perspectives. They need exercise, play, and relaxation; in short, they need a sound body and spirit to have a sound mind. Rather than spending their magical years entombed in cram-school dungeons that prepare them for impossibly difficult tests, children need old-fashioned schools where every day they can learn something new in classrooms that echo with laughter and joy! Unfortunately, it’s government policy to make sure schools are anything but the kind of places Breslin envisioned for students. By emphasizing standardized testing that evaluates how many predetermined facts a student can memorize rather than their capacity to conduct research and pursue their own lines of inquiry, America has created a citizenry increasingly predisposed to simply accept whatever they read uncritically. Now it is paying dearly for following that path.

The minds of children need room to breathe, to be inspired by vision, and the health-bringing balm of many perspectives. They need exercise, play, and relaxation; in short, they need a sound body and spirit to have a sound mind. Rather than spending their magical years entombed in cram-school dungeons that prepare them for impossibly difficult tests, children need old-fashioned schools where every day they can learn something new in classrooms that echo with laughter and joy! Unfortunately, it’s government policy to make sure schools are anything but the kind of places Breslin envisioned for students. By emphasizing standardized testing that evaluates how many predetermined facts a student can memorize rather than their capacity to conduct research and pursue their own lines of inquiry, America has created a citizenry increasingly predisposed to simply accept whatever they read uncritically. Now it is paying dearly for following that path.

At a time when we often bemoan the inability of Democrats and Republicans to work together on much of anything, it’s worth remembering that the pursuit of standardized testing has been a thoroughly bipartisan undertaking. President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation passed in 2001 with strong bipartisan support. In the speech he delivered before the student’s of Ohio’s Hamilton High School prior to signing the NCLB legislation, President Bush spoke of the importance of “accountability” and made it clear that a strong emphasis on testing was key to determining whether or not schools were meeting expectations:

The first way to solve a problem is to diagnose it. And so, what this bill says, it says every child can learn. And we want to know early, before it’s too late, whether or not a child has a problem in learning. I understand taking tests aren’t fun. Too bad. We need to know in America. We need to know whether or not children have got the basic education.

When President Obama took office, he initially doubled down on standardized testing. He too was, at least at first, clearly convinced that what was needed was a more objective measurement of a student’s knowledge. Though President Obama’s “Race To The Top” initiative did call upon states to “develop standards and assessments that don’t simply measure whether students can fill in a bubble on a test, but whether they possess 21st century skills like problem-solving and critical thinking, entrepreneurship and creativity,” it still placed an extremely strong emphasis upon standardization to ensure these goals were being achieved.

However, by 2015, President Obama was doing a mea culpa on standardized testing. He announced the amount of time spent in the classroom preparing for tests should be limited. In one of the more reflective moments of his presidency, Obama stated, “When I look back on the great teachers who shaped my life, what I remember isn’t the way they prepared me to take a standardized test.” He went on to admit that “too much testing, and from teachers who feel so much pressure to teach to a test that it takes the joy out of teaching and learning,” had caused more harm than good.

We live in a culture that places a high value on efficiency. Understandably, we want the next generation to have a firm grasp on certain basic skills that are essential to any real chance of success in the modern world. Reading, writing, and arithmetic — commonly referred to as “the 3 Rs” — are at the top of the list.

Unfortunately, the mastery of these skills doesn’t guarantee that a student has also learned how to put them to good use. While the United States has achieved a reasonably high literacy rate, increasingly people are using their ability to read and write to kill hours each day on social media rather than becoming informed citizens or otherwise enriching their lives.

According to a study just released by the American Psychological Association, the use of digital media by teens increased dramatically between 2006 and 2016. Jean M. Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University and the lead author of the study, states that social media use during leisure hours doubled among high school seniors during that period. Among 10th graders usage increased by 75% while among 8th graders it increased by 68%.

“In the mid-2010s, the average American 12th-grader reported spending approximately two hours a day texting, just over two hours a day on the internet — which included gaming — and just under two hours a day on social media,” Twenge is quoted saying on the science website Science Daily. “That’s a total of about six hours per day on just three digital media activities during their leisure time.”

According to the same Science Daily story, the steep rise in digital media usage has been associated with an even more extreme drop in the use of print media. The article states:

The decline in reading print media was especially steep. In the early 1990s, 33 percent of 10th-graders said they read a newspaper almost every day. By 2016, that number was only 2 percent. In the late 1970s, 60 percent of 12th-graders said they read a book or magazine almost every day; by 2016, only 16 percent did. Twelfth-graders also reported reading two fewer books each year in 2016 compared with 1976, and approximately one-third did not read a book (including e-books) for pleasure in the year prior to the 2016 survey, nearly triple the number reported in the 1970s.

Perhaps these trends wouldn’t be nearly as disconcerting if the rise in digital media use and the associated decline in the use of printed material wasn’t also coming at a time when so many members of the same generation were exhibiting such difficulty discerning between reliable news stories and fake news.

In a study coincidentally released just two weeks after the 2016 presidential election, Stanford University researchers reported students at all levels exhibited extremely poor skills when it came to conducting research and evaluating content online. According to the study’s executive summary, “Our ‘digital natives’ may be able to flit between Facebook and Twitter while simultaneously uploading a selfie to Instagram and texting a friend. But when it comes to evaluating information that flows through social media channels, they are easily duped.”

The Stanford study involved 7,804 subjects from middle school through university age. The sample comprised students from 12 states, including students from elite universities that rejected over 90% of their applicants and public institutions with high acceptance rates. Students were given age-appropriate problems to evaluate and research online including reasons to doubt the accuracy of content, assessing evidence, and verification of various claims. The results were not encouraging.

The Stanford team’s assessment of middle schoolers found that “More than 80% of students believed that the native advertisement, identified by the words ‘sponsored content,’ was a real news story.” Among high school students shown a post entitled “Fukushima Nuclear Flowers” with a picture of what appear to be white daisies exhibiting what were alleged to be various “birth defects,” the students “ignored key details, such as the source of the photo. Less than 20% of students constructed ‘mastery’ responses, or responses that questioned the source of the post or the source of the photo. On the other hand, nearly 40% of students argued that the post provided strong evidence because it presented pictorial evidence about conditions near the power plant.” The caption gave no indication where the photo was actually taken.

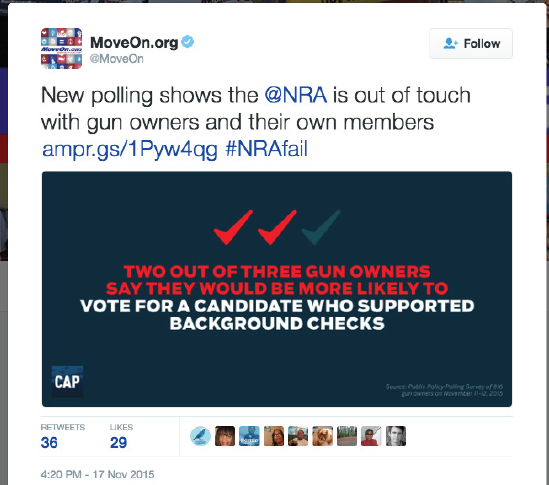

University undergrads from three different universities were shown a tweet announcing “new polling” on NRA members’ views on background checks for potential gun purchasers. According to the Stanford study, “Results indicated that students struggled to evaluate tweets. Only a few students noted that the tweet was based on a poll conducted by a professional polling firm and explained why this would make the tweet a stronger source of information.” Only a third of the students paid any attention to the agendas of MoveOn.org or the Center for American Progress and how that might influence the content.

When it came to undergraduate students, researchers also noted “An interesting trend that emerged” from their tests. Over 50% of “students failed to click on the link provided within the tweet.” In addition, “Some of these students did not click on any links and simply scrolled up and down within the tweet.” Others tried to investigate, but searched using the CAP acronym for the Center for American Progress provided in the tweet. This type of search “did not produce useful information.”

The use of fake news to influence the election of 2016, reveals it isn’t just our young adults that lack the skills to detect and resist misinformation. Many of their parents and grandparents also lack the critical thinking and research skills necessary to place information in context and separate the wheat from the chaff. In many respects, the most troubling aspect of this problem isn’t our apparent gullibility but our ongoing refusal to do much if anything about it.

The focus on standardized testing is a symptom of an education system literally designed to teach students what to think rather than how to think. Memorization, not research skills and hands-on learning, became even more of a focus as successive governments drank the testing Kool-Aid. Time-consuming experiments or other projects were dropped to make room for lessons that drilled the right answers into students. Arts programs that fostered creativity and instilled an appreciation for culture were cut or eliminated altogether in the name of efficiency. Our schools became factories that mimicked the routinized schedules of the workplace while denying students the chance to ask questions, challenge the ideas being presented to them, and figure things out for themselves.

It doesn’t have to be this way. A recent episode of the BBC World Service podcast The Documentary highlighted work being done to determine the best approaches for instilling in children a basic grasp of what qualifies as evidence and the importance of understanding the basis of the claims they will inevitably hear from salesmen, politicians, and even family members over the course of their lives. The program, entitled You Can Handle The Truth, doesn’t just reveal how successful such efforts can be but how much delight children actually take in learning how to unmask poorly supported assertions and outright falsehoods.

The program’s host, the British statistician Sir David Spiegelhalter, traveled to Uganda to see the results of these efforts for himself. Researchers and educators in that country had been working with a Norwegian team on educational materials designed to teach elementary age students how to make more informed health choices.

The young Ugandan students were given a comic book that depicted individuals confronting a number of difficult choices. Among the most popular comic book characters is a parrot that, as parrots are known to do, repeats back everything it hears unquestioningly. Over the course of the school year, students discussed the various scenarios described within the book with their teachers and learned the importance of asking those making a claim what the basis for it was and how to better evaluate the answers they heard in response.

The Ugandan program involved 10,000 students from 120 schools. Sixty of the schools were placed in a control group. Students at these institutions received no additional instruction. In the remaining 60 schools, students participated in lessons and activities designed to provide them with basic critical thinking skills. At the end of the year, students from all 120 schools were tested and the differences between the control group and the test group assessed.

The results of that testing revealed the program had produced the desired effect and in a big way. All students were given 24 problems to solve or evaluate. Thirteen right answers were considered a passing grade. The 24 questions presented to students on the test were unique and had not been problems considered as part of the critical thinking curriculum.

In the control group, 27% of the students passed the test. In the intervention group, 69% received a passing score. Even teachers in the two groups were tested. Among the control group’s teachers, 87% passed, while the intervention group saw 98% of the teachers get a passing grade.

One of the problems the researchers anticipated but never encountered is one that will likely sound familiar to Americans; parents becoming upset as their children begin coming home from school with tough questions about cherished beliefs and cultural practices. Uganda is a country with a rich history of folk remedies and superstition. Researchers feared that having children go off to school in the morning happily accepting particular family or cultural traditions only to return in the evening wondering about the basis for the claims surrounding grandma’s famous herbal remedy could turn parents against their efforts.

However, Ugandan parents, at least so far, haven’t made a fuss. Their children are excited to be learning and take delight in being empowered to question their elders about things that have been taken for granted for generations. To everyone’s surprise, parents and other family members don’t seem to mind.

Sir David Spiegelhalter also took a trip to California for his BBC program. That state is currently considering legislation that will mandate media literacy education. Spiegelhalter paid a visit to one California classroom where students were asked to research various theories into who or what sank the Battleship Maine in Havana’s harbor on February 15, 1898. The sinking of the Maine ultimately led the United States into a war with Spain.

American parents aren’t likely to get too upset if their children conclude an American battleship that sank over 100 years ago went down due to an accident instead of a Spanish mine as was widely assumed at the time, but it’s hard to imagine many of them remaining silent when it comes to climate change, evolution, vaccines, or race relations. They haven’t so far. In just the past year Mark Twain and Harper Lee were targeted by the school board in Duluth, Minnesota because their books contained language that might make students feel “humiliated or marginalized.”

One of the appeals of the reading, writing, and arithmetic mantra is that learning these skills, at least in theory, doesn’t require teachers to raise too many questions or address contemporary controversies. Once a kid has the capacity to read, it’s just assumed they will figure it all out for themselves as an adult when and if they choose to. But learning to read is about more than just memorizing the alphabet and passing a spelling test. It’s about how to think too.

The California media literacy bill failed on its first attempt in 2017, but it’s back again this year. If it passes, implementation will certainly be carefully watched to see what kind of impact it has on students being thrown into the sea of digital technologies we’ve created. Will they sink or swim? One thing is certain, however; it increasingly appears as though everything is riding upon their capacity to keep their heads above water.

In the August 27 issue of the New York Times, the author Thomas Chatterton Williams reviews two new books hitting the shelves: The Splintering of the American Mind and The Coddling of the American Mind. As the titles suggest, their authors rue the polarization, hypersensitivity, and inability to cope with controversies that now grips Americans right across the political spectrum.

But what got my attention wasn’t Williams assessment of these newly published works so much as the closing paragraph of his review. It was clearly more about us than it was either of the books he had just shared his thoughts on. Williams concludes:

What both of these books make clear from a variety of angles is that if we are going to beat back the regressive populism, mendacity and hyperpolarization in which we are currently mired, we are going to need an educated citizenry fluent in a wise and universal liberalism. This liberalism will neither play down nor fetishize identity grievances, but look instead for a common and generous language to build on who we are more broadly, and to conceive more boldly what we might be able to accomplish in concert. Yet as the tenuousness of even our most noble and seemingly durable civil rights gains grows more apparent by the news cycle, we must also reckon with the possibility that a full healing may forever lie on the horizon. And so we will need citizens who are able to find ways to move on despite this, without letting their discomfort traumatize or consume them. If the American university is not the space to cultivate this strong and supple liberalism, then we are in deep and lasting trouble.”

The anti-democratic forces that are currently so vocal in the United States would no doubt frame the kind of educational goals Williams identifies as some sort of conspiracy to destroy their movement and they would be right. They will claim that any attempt to instill in children critical thinking skills and an understanding of the nation’s history, laws, and aspirations are biased because these efforts fail to treat their own anti-intellectual, unscientific, and undemocratic points of view as worthy of equal of time. Again, they will be correct.

Freedom of speech means everyone gets to express themselves. However, it does not mean that every idea deserves equal press coverage or even any press coverage at all. Thinking is hard work precisely because it requires us to critically evaluate the concepts we’re exposed to. It determines not only what is and isn’t worthy of our time and attention but which ideas have the potential to either threaten or enrich our lives and those of our fellow citizens.There are sound methods for making these determinations that have proven themselves over and over again, but they can’t do us any good if we refuse to learn them.

No comments:

Post a Comment