Alex Lo

To cut a long story short, though, you would probably be disappointed with my answer. At crucial junctures, the party learned the wrong lesson or ignored the right one that was staring at it, leading to complete disaster for the country.

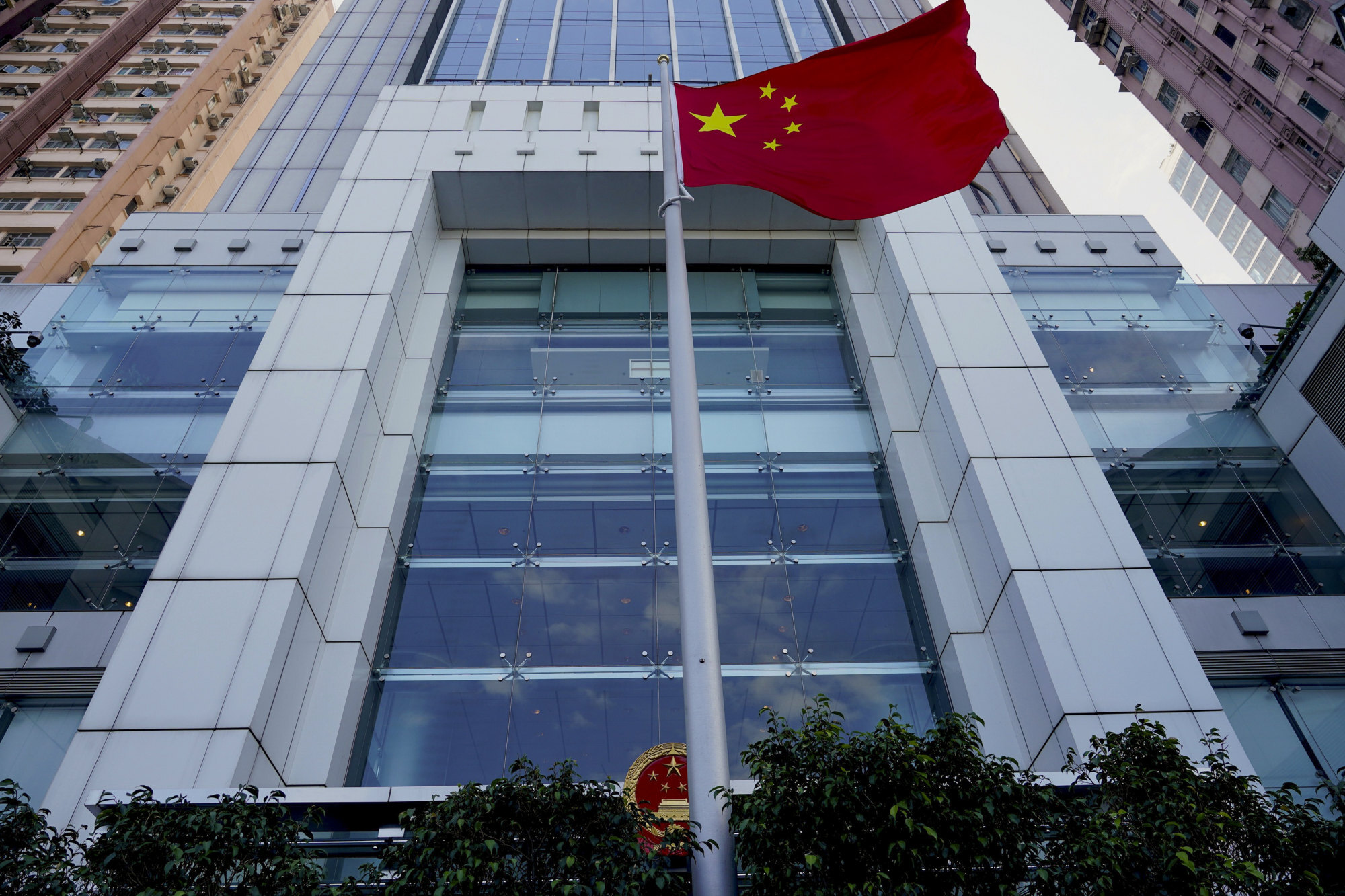

At crucial junctures, the Chinese Communist Party learned the wrong lesson or ignored the right one, leading to complete disaster for the country. Photo: AP

But in other instances, it took the right lesson or at least drew the right conclusion, thereby not only avoiding disasters but also leading to growth and national renewal. So, the records are mixed, as they tend to be.

Strictly speaking, then, what Hegel supposedly claimed actually isn’t true; there is at least one government having learned correctly from history in at least one instance. Actually, there are many incidents of governments and peoples learning the right lessons, throughout history; though admittedly, the rate of failure far outnumbers success.

Still, I have never understood why so many people take this supposed remark of Hegel so seriously when it’s actually not true, not completely anyway; and when there are many other things that Hegel wrote about history and government which should be taken absolutely seriously and yet are rarely discussed.

But at least his remark was more accurate than that other saying of George Santayana, about repeating history, which I won’t bother to repeat here.

It’s not that people don’t learn from history, but they learn too much, yet rarely, as Hegel might say, draw the right lessons. In any case, what’s the right lesson for me may be the wrong lesson for you.

Then-Chinese president Liu Shaoqi and his wife Wang Guangmei, during the famine following the Great Leap forward, picking wild fruit and grasses near Guangzhou. Photo: Xinhua

Just think “Munich”, and what the word might signify for a historical lesson.

For many Western, especially American politicians today, it would mean the world must confront China, now, before it’s too late. I would say that’s absolutely the worst history lesson you could draw from Munich in 1938.

But apologies, I digress. Back to communist China.

The great Chinese famine of the late 1950s and early 1960s is well known to most people following the Great Leap Forward. The Chinese communists would have known that agricultural collectivisation and centralisation could end in disaster when the Soviets had already provided plenty of warnings and evidence.

Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai walks with then -US president Richard Nixon during a trip to China. Photo: Getty Images

But the other side of learning the wrong lesson from the Soviets is failing to learn the right lesson from the socialist Indian state planners after their country’s independence.

Throughout the 1950s, as recounted by a fascinating book, Making It Count: Statistics and Statecraft in the Early People’s Republic of China, by Harvard historian Arunabh Ghosh, some Chinese state planners and statisticians were working against Maoist orthodoxy and conducting extensive exchanges – including mutual country visits – with their Indian counterparts led by Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, who applied the most advanced statistical methods of his time to economise socialist planning for the government, especially in the agricultural sector.

Mahalanobis was not only an influential state adviser but also one of the most important statisticians of the last century, having made fundamental contributions to the discipline.

After Mao’s death, the Chinese did take the right lesson from the Soviets, as well as from some Eastern Europeans who had also learned from Soviet mistakes under Stalin. Photo: Simon Song

At a meeting with Mahalanobis, Premier Zhou Enlai was intrigued by the new statistical methods. Ghosh wrote: “‘What are the countries most advanced in statistics? Are you in touch with them?’ Zhou Enlai’s pointed questions had come at the end of a longer-than-planned visit to the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Calcutta on 9 December 1956. Enamoured and intrigued by what he saw, Zhou had become deeply involved in several displays, asking questions and seeking clarifications.”

No doubt the socialist planning blueprint would come back to haunt India in later years, with its inefficiencies, wastage, subsidies and corruption. The ongoing farmers’ protests today have a long history behind them. But compared to the Chinese communists, Indian state planning back then was a triumph of reason and rationality.

Suppose Mao Zedong had learned from Jawaharlal Nehru rather than Joseph Stalin …

But after Mao’s death, the Chinese did take the right lesson from the Soviets, as well as from some Eastern Europeans who had also learned from Soviet mistakes under Stalin. Before Chinese Communist reformers started the so-called household responsibility system, Soviet Russia already had something similar.

It started at about the same time as Khrushchev’s attempt at reforming agricultural collectivisation, which was still highly centralised in planning and also ended in failure.

The Soviets’ “micro” farms were a lot like the partitioned plots of land used by Chinese farmers to grow what they liked and to keep the profits (or losses) under the so-called household responsibility system in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

TsoviInstead, private small farms proved their real worth, against Soviet communist ideology and propaganda.

Tony Judt wrote in Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945: “At the same time, the private micro-farms that Khrushchev had sporadically encouraged were almost embarrassingly successful: by the early sixties, the 3 per cent of cultivated soil in private hands was yielding over a third of the Soviet Union’s agricultural output.

“By 1965, two-thirds of the potatoes consumed in the USSR and three quarters of the eggs came from private farmers. In the Soviet Union as in Poland or Hungary, ‘socialism’ depended for its survival upon the illicit ‘capitalist’ economy within, to whose existence it turned a blind eye.”

In a footnote, Judt added: “The credibility of the Soviet system rested to a quite extraordinary extent upon its capacity to get results from the land. For most of its 80-year life, agriculture was on an emergency footing in one way or another.”

Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Communist reformers would embrace small-scale private farming. Photo: AFP

The Soviets’ “micro” farms were a lot like the partitioned plots of land used by Chinese farmers to grow what they liked and to keep the profits (or losses) under the so-called household responsibility system in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Rather than going hush-hush about it like the Russians, Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Communist reformers would embrace small-scale private farming.

Eventually, they would extend “capitalist” methods to other sectors of the economy, as they learned about price signalling and how to address “the economics of shortage” from such influential and reform-minded central European economists as the Czech Ota Sik and the Hungarian János Kornai.

One big win for the Chinese Communist Party about learning from history, and other people’s experience! Of course, the household responsibility system did not just come from Chinese reformers. Droughts in some rural areas caused farmers to get creative at the now legendary Xiaogang village, in Fengyang county, Anhui province.

Since it was against the rules at the time, people kept quiet about it until it was endorsed by communist reformers.

But it’s almost certain that at the time, the Chinese leaders would have known about the success of micro-farming in the USSR.

So, was Hegel really wrong – about governments and peoples never learning from history? I have read plenty of Hegel in my life and have never come across that famous remark attributed to him.

Still, I might have just missed it as you tend to fall asleep after a few pages of dense Hegelian prose. More erudite readers are welcome to help out and point to the source of that quote. I suspect it’s apocryphal.

No comments:

Post a Comment