Richard Hanania

The American culture war is part of a global trend. The German far right marches against covid restrictions and immigration. In France, Le Pen wins the countryside and gets crushed in urban centers. Throughout the developed world you see the same cleavages opening up, with an educated urban elite that is more likely to support left-wing parties, and an exurban and rural populist backlash that looks strikingly similar across different societies.

What explains this? I think a good theory needs to do two main things. First, it has to explain things that are happening globally by pointing to factors that are operating across borders; otherwise we wouldn’t see the same trends everywhere we look. Second, it needs to explain why this polarization appears to be particularly bad in the United States, hopefully being able to isolate variables that exist here and not in other nations.

This article presents a psychological theory of the culture war, and posits a dynamic social system in which the actions, rhetoric, and behaviors of each side influence the other. People are not seeking their own economic interests nor even working towards a moral vision, but responding to a built-in drive towards trying to achieve status, which involves tearing others down. It’s something of a LARP because those who are most unaware of their own motivations can act with the most certitude, and therefore have the largest effects on our political culture. In its most extreme form, my model suggests that if all the hot-button issues that supposedly cause so much division in this country like abortion and immigration were taken off the table, it wouldn’t have all that much effect on the level of class resentment we have, which is the fuel of the culture war. I’m not sure I’d go that far, but I’m sort of tempted to. See this theory as claiming that issues are overrated as causes of our divides, rather than them not mattering.

Neither faction comes across particularly well, which is why it is unsurprising that this is as far as I know a novel theory. In sum, I think the best critiques of the left come from the right, and vice versa. In fact, in certain ways neither side goes far enough in pointing out what is wrong with its opponents. This essay is not meant to be taken as misanthropic. After all, politics remains a small part of most people’s lives, and so I don’t judge them for their views or the instincts they indulge in. At the same time, I see the culture war as being driven by the psychological dispositions and mental processes of a small minority of the population on both sides, and I do in fact have very negative attitudes towards the main antagonists in our great battle. These active minorities form the two poles around which the rest of our politics tends to organize, as people feel themselves repulsed more by one side or the other.

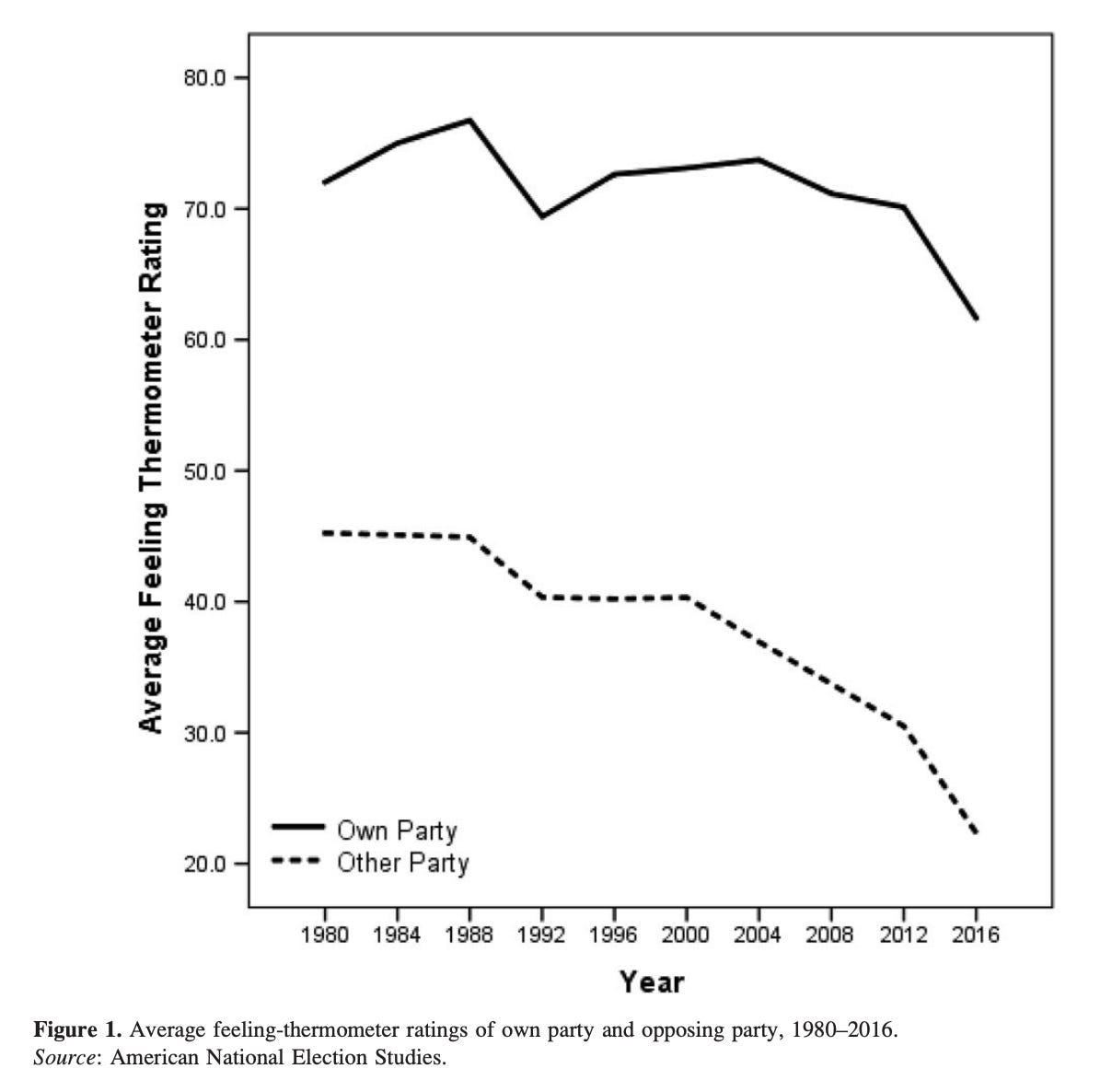

Over the last four decades, Americans increasingly dislike their own party, but have come to dislike the opposite party at an even faster rate, as the chart below demonstrates.

All of this means that when I talk about the “upper class” or “elites,” on the one hand, or the “lower class” or “proles,” on the other, you should understand that I am referring to the most politically conscious and active segments of each population.

Moreover, I don’t feel hostility towards those who end up supporting one side or the other in the culture war as a necessary evil. This is a descriptive theory, and isn’t meant to tell you who to vote for, or even whether you should be a conscientious objector to the whole thing.

With those caveats in mind, the theory posits the following process.

Increasing wealth causes class differentiation and segregation. One thing people with money buy is separation from poor people or others not like them, while assortative mating moves these trends along.

With modern communications technology and women playing a larger role in intellectual life, genetic (i.e., true) explanations of class differentiation are disfavored, as is anything that would blame the poor or otherwise unfortunate for their own problems.

Despite social desirability bias leading to the triumph of egalitarian ideologies, the natural tendency towards a kind of class consciousness does not go away. The higher class therefore becomes more strenuous in defining itself as aesthetically and morally superior to the lower classes. Part of this is based in reality, as the upper class is indeed smarter and more competent, with more sophisticated tastes. Part of it is adopting arbitrary symbols that appeal to their vanity, like fake academic degrees and appreciation of postmodern art.

The more egalitarian the official ideology, the harder the upper class has to work to find some other grounds on which to differentiate itself from the masses, leading to an exaggeration of the moral differences between the two tribes. Members of the lower class don’t understand much, but they do understand when others hold them in contempt. They therefore react to the upper class by becoming caricatures of what the higher class thinks they are, clinging to religion, traditional morality, and nationalism.

The upper class sees all of this, and finds confirmation for its sense that the lower class is morally and aesthetically inferior.

The lower class senses that the upper class has even more extreme contempt for it than before, and….

…we find ourselves in an infinite loop. The steps above can apply to pretty much all developed countries, because all of them have had the three exogenous forces that create the modern culture war: increasing wealth, women playing a larger role in intellectual life, and modern communications technology. In the American context, there are three specific factors that make our culture war particularly virulent and entertaining.

We have a high crime rate and extreme dysfunction among the very bottom rungs of society, which increases the costs of living around poor people, thus creating more class segregation.

The failures of African Americans to economically succeed and integrate into the larger society makes elites cling to blank slate explanations of human differences more tightly. The desire to avoid genetic explanations for racial differences in outcomes increases the tendency to want to ignore genetic explanations of class and individual outcomes, which makes it even more imperative than it is in other countries for elites to differentiate themselves from the masses based on something other than the idea of inherent superiority.

Our political system is more “democratic,” due to the First Amendment and the fragmented nature of our system that puts power in the hands of local governments. This gives the lower classes more of a say in the government, which increases parity between the two sides and increases the intensity of the struggle.

In doing this kind of grand theorizing, there are certain parts of the model that I’m certain about, and others that I’m less sure of. In describing each step in the process below, I’m going to indicate a confidence level. This will also serve to clarify what is essential to the theory, and what can be ignored without losing much.

Against Economic Theories

Before getting into the main theory, it is important to set the theoretical background and explain why you should be looking for culture war explanations in human psychology, rather than economics.

Economic explanations for the culture war usually involve some group manipulating the masses to ignore their “true” economic interests. For liberals, Republicans have seized on culture war issues as a way to distract their voters and prevent poor people of all races and backgrounds from coming together and pushing for redistributionist policies. This was the thesis of Thomas Franks’ 2005 book What’s the Matter with Kansas? Such an argument is strikingly similar to the idea presented by Vivek Ramaswamy in Woke, Inc., in which he contends that corporations got everyone focused on identity politics a decade ago to deflect the demands of Occupy Wall Street.

These theories aren’t completely wrong, but when they are correct they beg the question of where the culture war ultimately comes from. Traditionally, Republican elites, committed mainly to tax cuts and a strong American presence abroad, have used culture war issues as a way to gain power, often without intending to do anything about the concerns of their voters. And corporations may find it much easier to support wokeness than economic redistribution, as the former does much less damage to their bottom line.

Nonetheless, while it is fine to point out the ways in which Republicans or corporations have used the culture war to their own advantage, this doesn’t explain why they find it so easy to do so. Why is there a rural-urban divide that revolves around issues related to race and sexuality in the first place? And why do we increasingly find some version of this divide across the developed world?

Another kind of economic explanation doesn’t see elites fooling the masses, but argues that both the elites and masses are ultimately acting in their own interests. Michael Lind, a kind of culture conservative New Dealer, takes this sort of crude materialism in some extremely bizarre directions, for example arguing that urban elites want to defund the police to create more jobs for social workers. Presumably, lower class types would be against defunding the police because they would be more likely to work as cops and suffer the consequences of increased crime.

I do not doubt that financial interests can explain some things about our politics. That’s why I wrote an entire book on how special interests drive American foreign policy. Yet as Mancur Olson taught us, for the individuals who form a potential interest group to be rationally expected to work together to influence a policy outcome, they must have incentives as individuals to do so. This ultimately means at the mass level, you should be skeptical about group interest theories. Caplan points out in The Myth of the Rational Voter that a single vote never changes an electoral outcome, at least at the state or national level. A voter who was acting in his own material interests would stay home, not choose a candidate who promised to lower his taxes or give him more welfare benefits. Political scientists call this “the paradox of voting.” Indeed, we do find that economic interests are an extremely poor predictor of political attitudes, as theory would predict.

In other words, the idea that the military-industrial complex influences foreign policy is potentially a good theory, because all you need to believe is that a handful of corporations have an incentive to take political action. In contrast, you should be very skeptical of any theory in which an “interest group” is composed of millions of people. To say Raytheon, a trial lawyer lobbying firm, or the CIA acts in its own interests makes sense; to attribute some common goal to “whites,” “blacks,” “the rich,” “the managerial class,” or “economic elites” does not.

Special interest lobbying is driven by relatively small, concentrated interests. Voting and mass attitudes are matters of psychology, or more specifically a search for status and a way to express flattering narratives about one’s self. With that in mind, we can start to think about what a plausible theory of the culture war might look like.

Step 1: Wealth Leads to Genetic Stratification and Class Segregation

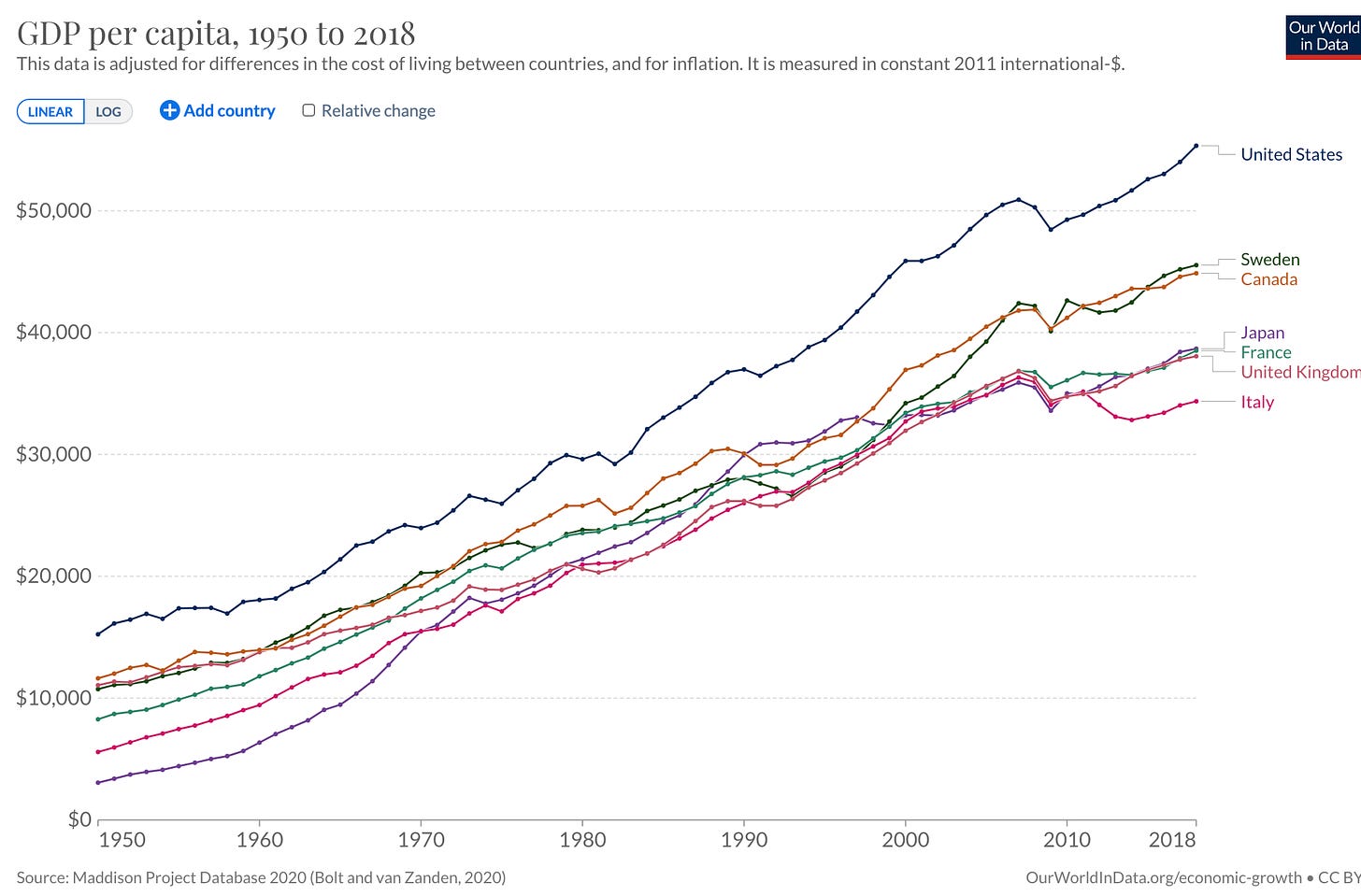

The first thing to note is that modern societies are much wealthier than they were a few decades ago. Here is a chart showing GDP per capita from 1950 to 2018 in select advanced nations.

We rarely stop and think how much better off we are than previous generations. Sweden was a relatively wealthy country in 1950, but its GDP per capita that year in 2011 dollars was $10,700, lower than the current average for Latin America. In 1965, the US, in the midst of its post-war boom, was at $23,400, lower than the average for Malaysia today. The United Kingdom didn’t rise to the level of modern Malaysia until the mid-1980s. If you think that going from third world status to being a developed economy today will lead to inevitable changes in a society, you should be just as convinced that the most advanced nations have seen major developments that were bound to be beyond anyone’s control. Moreover, I’m of the firm belief that changes in GDP over time underestimate how much better off people are today, as economic stats don’t seem to do a very good job of capturing improvements in the qualities of goods and the benefits of the internet and communications technology.

There are two important consequences of this growth. First of all, wealthier societies can afford to spend more on education, which is mostly, but not completely, about signalling. Yet, as behavioral geneticists have pointed out, the more you equalize environments, the more that genes are able to explain individual outcomes. Modern society invests so much money in educating practically all children that they all reach something close to their full potential. The rich spend more on their children than the poor, but there are radically diminishing returns to doing so. As society got wealthier, people became better fed, and schooling increased, IQ scores rose across most of the twentieth century. This was called the Flynn Effect, which started reversing around the 1990s as the gains to be squeezed out of the environment had reached something close to their full potential and dysgenic trends started to be reflected in measures of cognitive ability.

One thing that people buy with new wealth is space and privacy. They also seek out more people like themselves. Hence, there is increasing segregation, both in terms of economics and political or moral values. For the upper class, living around poor people is unpleasant; they tend to be louder and more criminally inclined, and less appealing as friends, conversation partners, and potential mates. Hence when those with money can afford to do so, they move away from them. Over the decades, greater wealth has correlated with more socioeconomic segregation across the US , Europe, and the developing world. The wealthy want to separate from the poor not only geographically, but in clubs, schools, employment, and social life. This change is documented by Charles Murray in Coming Apart, but although the author does a good job of diagnosing the issue, he seems hesitant to admit it is the natural result of greater wealth and freedom.

It is not a simple matter of the rich moving away from the poor. Imagine a young man inclined to seek a PhD in literary theory. Thirty years ago, maybe he gets a stipend of $15,000 a year, which means he pursues his education at a local school he can commute to and stays home with his parents until completing his studies. Today, he gets a stipend of $40,000 a year. The young man is by no means rich, but he does have enough money to live on his own on a university campus and therefore cuts ties with his local community, which he probably always found distasteful since he chose to study literary theory in the first place instead of getting a productive job. Everyone is getting wealthier, which means that everyone has more freedom with regards to which communities they opt in and out of at every level of income. All of this leads to assortative mating, hence increasing the differences between classes even more than before.

Confidence level: I’m absolutely certain genes are causing class differentiation, and that those in the first world are much wealthier than they were in previous decades. I’m also pretty confident that those with money want to avoid the poor, and people generally would rather be around those like themselves. Step 1 rests on extremely solid grounds.

Step 2: Communications Technology and the Education of Women Lead to the Triumph of Egalitarian Ideology

Ironically, as society becomes more “fair” and genetic qualities come to better explain class differences, intellectual life comes to more strongly revolve around blank slate theories. This is because of social desirability bias – the idea that poor people are poor because of their genes sounds too unpleasant to acknowledge. This hasn’t always been the case, since before modern communications technology, the upper class could have discussions about the masses without them hearing.

When all intellectual discourse took place through the written word, elites generally only talked to one another. The American Founders, for example, could acknowledge natural differences between individuals. As time went on, however, the population urbanized, literacy increased, and demagogues could more easily recruit among the poor and downtrodden. The development of radio, and later television, brought into the conversation those not inclined to read anything. Finally, the internet allows instantaneous communication across the world. Infotainment, fake news, and boomer memes start to play a role in the political discourse. Women, of course, increasingly become part of the intellectual elite, and they are more prone to social desirability bias and therefore false egalitarian theories.

When elites were just a small group of men talking to each other, they only had to worry about each other’s feelings. This probably contributed to what are today called “racism” and “misogyny,” as white men assured one another that even the worst among them were superior to other groups and deserved to be the ones in charge. Now, with mass literacy and modern communications technology, we have a more inclusive conversation that includes women, minorities, the rural poor, elderly people in the early stages of dementia, and practically everyone else with an internet connection. Under those circumstances, it sounds too mean to attribute poverty, or even poor aesthetic taste, to some kind of natural defect. Of course, psychometrics and cross adoption and twin studies, along with GWAS, continue to establish more firmly than ever that in explaining differences in socioeconomic outcomes within a developed country, genes are the dominant factor. But greater ability to communicate scientific truths is no match for social desirability bias.

In the early twentieth century, prominent American politicians were supporters of eugenics. Teddy Roosevelt became president despite having once said, “I wish very much that the wrong people could be prevented entirely from breeding.” He could make statements like this when the politically engaged public was only men smart enough to read books or articles. He had very little reason to fear that anyone would see his quote and believe he was talking about them. I haven’t done a study of this, but my impression is that Roosevelt and other elites of the time talked more about genetic differences between people in books and articles than in speeches and on the radio.

If Roosevelt was running for president today, political opponents would dig up such quotes, run them on a loop on cable news, and dunk on him on Twitter. By the time of FDR, politicians had found that a winning formula was for them to tell poor people they weren’t to blame for their own problems and that the federal government should help them.

People usually see intellectual influence as top-down, as in Curtis Yarvin’s idea of “the Cathedral.” Just as often, major trends can be explained by elites or aspiring elites looking for ways to flatter the masses in order to gain power. I encourage you to watch and ruminate on the multiple videos of Trump getting booed by his followers for praising the vaccine he helped create. It seems to me that “intellectual Trumpism” in recent years has been an attempt to reverse engineer an ideology to fit what Republican voters were doing. Of course, the explanation can’t be that there’s something wrong with the voters for following this guy. That was the conclusion of the Never Trumpers, and for sticking to that belief they’ve lost all their political influence within the Republican Party. Those that played to the hopes and fears of the masses ended up displacing the old GOP leadership. This is the mirror image of how identity politics took over the left: women’s tears in education establishments and white-collar workplaces lead to modern feminism, and inner-city riots originally helped create race conscious policy.

In the age of social media, we therefore have two grievance parties, one that talks about “white supremacy” and “patriarchy” and the other going on about the “deep state” and “liberal elites.”

The triumph of egalitarianism goes beyond the denial of genetic differences, but includes a refusal to even acknowledge behavior could have some impact on life outcomes. The idea that poor people are always the victims of forces beyond their control has become the standard way to discuss inequality and poverty. Other defects like mental illness and criminality are now treated with more “compassion” than before, which in general leads to false beliefs about their origins and potential solutions. Republicans have been a major holdout against this trend, but the rise of populism has brought the party closer to the Democrats in how it understands and explains individual and class differences.

Confidence level: Not completely sure about this one. It’s possible that the triumph of blank slate ideology didn’t have much to do with communications technology or even women entering intellectual life. Blaming Step 2 on exogenous forces makes the theory more elegant. But it’s possible that something else is responsible for the triumph of egalitarian ideology, the influence of which we can accept without changing the rest of the theory. The more important point is the effects of egalitarian ideology, not its origins.

Step 3: The Upper Class Defines Itself as Morally and Aesthetically Superior

The real source of class difference is traits like IQ and intellectual curiosity. This has always been true to a certain extent, and it is truer than ever now. Even without blank slate ideology – or even the ability to acknowledge behavioral differences between classes regardless of the source – the upper class needs a way to distinguish itself from the masses.

Judith Rich Harris writes about the inevitability of group conflict in The Nurture Assumption.

…when human groups split up, individuals tend to choose the side with which they are most compatible: like seeks like. In the case of groups composed of families, such as human communities, most individuals have no choice about which way to go, but those who do will go to the side with which they have the most in common. The result will be, in many cases, a statistical difference between the daughter groups. There might be some minor behavioral difference between the members of the two groups, or some minor difference in appearance. Then again, there might not be.

In humans, hostility between groups leads to the exaggeration of any preexisting differences between the groups, or to the creation of differences if there were none to begin with. You may have thought it was the other way round — that differences lead to hostility — but I believe it is more a case of hostility leading to differences. Each group is motivated to distinguish itself from the other because if you don’t like someone you want to be as different from them as possible. So the two groups will develop different customs and different taboos. They will adopt different forms of dress and ornamentation, the better to tell friend from foe in a hurry.

Harris calls this process pseudospeciation. In previous generations, when there was a weaker relationship between class and IQ, people were more likely to have other identities – regional, ethnic, etc. – that were more salient for their politics. An upper-class individual from North Carolina could feel he had more in common with local proles than the upper class in Illinois. Today, given greater class differentiation, and multiple generations of families living within the same IQ-based class stratum, the chasm between them and the lower classes seems much more relevant. The upper class need not have much direct contact with the lower class to realize this; reading about what proles are like or familiarity with their sources of entertainment or voting practices is enough to create a strong sense of difference. Modern communications technology helps with all of this, as elites in North Carolina and Illinois both read The New York Times instead of their local papers.

To the extent there was a broad upper class identity in previous generations, it had more of a foundation in truth. The upper class saw itself as smarter, more refined, and better able to exert self-control. It therefore cultivated these traits. Now, with that obvious path to class differentiation closed off due to egalitarian ideology, something must come to replace it.

Go to a museum and look at paintings from the Renaissance, and people from all classes can agree on what the best pieces of art were. It’s only in the last hundred or so years that one sees wide class divergences in artistic tastes, as elites came to need a new way to distinguish themselves. When poor people in the most advanced nations didn’t have enough to eat and a large portion of their children died in the first year of life, it would’ve seemed in bad taste to create new art movements in order to humiliate them further. It would be like wealthy Americans seeing themselves in competition with the third world today. In a modern first world country, the lower class is to a large extent distinguished by its lack of intelligence and poor taste, and it is in fact living quite well in absolute terms, so one feels more comfortable denigrating its members.

To summarize, the rise of egalitarian ideologies throughout the twentieth century went hand-in-hand with the rise of new art forms that created a wedge between elites and the masses, and this is unlikely to be a coincidence.

All of this is why concern with immigration is a class issue, as to feel affronted or threatened by Mexican gardeners indicates that one is extremely low status. While attitudes towards immigration are often thought to be based on economic interest, they are really to a large extent a matter of lower-class Americans looking down on poor migrants, and upper-class Americans looking down on lower-class Americans. We can see that it is not about group interest in the fact that academics compete more directly with immigrant labor than those in the vast majority of other professions.

A certain degree of class differentiation in aesthetic taste is natural; some people are going to like reading Shakespeare, and others want to go see cars drive around in circles. But the distortive effect of egalitarian ideology is such that the elite need to differentiate itself gets to the point where the upper class can’t stand the thought of having anything in common with its inferiors, and more of life comes to be dominated by this impulse. The upper class has to pretend that mayonnaise doesn’t taste good, or that feces is great art. For the status conscious, architecture, sculpture, food, painting, clothes, and sexual tastes and preferences all become class markers.

The same thing happens with politics. The upper class supported the public acceptance of homosexuality in part because it grosses people out. When it won that battle, it moved on to trans ideology, because the point is less some abstract moral conviction than it is about feeling superior. It is like this with every other social issue. Today, the “conservative” position on gender and race is always the liberal position from a generation or two ago, but the modern liberal position always has a need to go one step further in order to establish distance between itself and the rest of society.

When I was a graduate student, I was once in some TA training seminar where they were trying to teach us how to speak respectfully to others. At one point, a foreign student asked why “people of color” was a good term and whether he could say “colored people.” The American-born instructor was horrified by the question and told him flatly that he couldn’t say that, but she had no answer when he asked why. An honest and self-aware response would have said something like “‘colored people’ is associated with the lower classes, while ‘people of color’ was invented and is used by people like us. It’s now circa 2014 though, and they’re catching on, so we’ll be moving on to BIPOC soon.”

Confidence level: I’m pretty sure that a great deal of woke politics and appreciation for modern art is a class marker and tied to the need for status. I also feel confident there’s a connection between egalitarian ideology and the need of the upper class to find other sources of status, although I admit it is ultimately unknowable how big of a factor this is in shaping elite politics and culture.

Step 4: The Lower Class Notices and Reacts

In the development of artificial intelligence, researchers have found that there are certain tasks that machines do better than humans, and others where our best technology can’t match our dumbest people. If you want to instantaneously multiply two 8-digit numbers, you should use a simple calculator. If you want to remember and distinguish human faces and voices, people can match our most advanced technology. Humans are not wired to understand economics or public policy very well. But even the least discerning members of the public are hypersensitive to distinctions of status and rank. According to the Social Brain Hypothesis, the need to form and manage complex relations is what made us develop such large brains in the first place.

When a member of the public hears two politicians argue about international trade while citing facts and statistics, nothing in his evolutionary background equips him to be able to figure out whose policy will make him or the country better off. He may end up preferring the candidate with the best plan, but if so it’ll only be by accident. In contrast, the average voter is a savant when it comes to knowing who respects him and who doesn’t, and he develops his political loyalties accordingly.

Egalitarian ideology formed because elites wanted to avoid insulting the masses. Ironically, the old ways of differentiating social classes that seemed too harsh were replaced by something that engenders even more bitterness. Liberals used to argue that there was something hypocritical about someone as wealthy as Trump presenting himself as a populist champion against the elites. This critique is based on a misunderstanding of the roots of the culture war. People can accept the fact that some people are more intelligent, hard working, and successful than others. When Trump tells people he’s better than them because he has a lot of money and a supermodel wife, the natural response is “yes, that’s a good reason to think you’re superior.” He is at least giving the lower class the respect of speaking its own moral language. It’s not an act, as the guy does share their instincts and tastes. Before Trump, there was Bill Clinton, the last national Democrat able to win over the white working class. Like them, he felt genuine affection for McDonald’s and buxom women, and they could sense this. Modern liberals, in contrast, are constantly sending the message that they are superior to the masses based on morality and aesthetic preferences, which is much more insulting than Trump explicitly riffing on how stupid normal Americans are, particularly given the nature of upper-class symbols that can be rejected on common sense grounds – sympathy towards criminals, deranged anti-white rhetoric, gender ideology, postmodern art, etc. No one is silly enough to actually believe in a society without any kind of class distinction, except maybe the people who accepted egalitarian ideology as a class marker itself.

Paul Fussell, in his book on the American class system, which was originally published in 1983 but still holds up well, writes that,

At the bottom, people tend to believe that class is defined by the amount of money you have. In the middle, people grant that money has something to do with it, but think education and the kind of work you do almost equally important. Nearer the top, people perceive that taste, values, ideas, style, and behavior are indispensable criteria of class, regardless of money or occupation or education.

The lower class sees money as a marker of status because it doesn’t have any other option, as it is less intelligent and capable of understanding the subtleties required to develop upper-class preferences and tastes. Fashions change so fast that just keeping up requires mental energy, which is lacking among the lower IQ. Trans ideology was being pushed in college seminars and New York Times op-eds before it made it on to TV and into mass advertising campaigns, hence giving the intelligent and aware a head start of several years in their ability to use the issue to raise their own status and denigrate others. The fact that the rules are so arbitrary and ever-shifting is part of the point – this serves to exclude those incapable of following along. In fact, the entire idea of making aesthetics and taste the basis of a status system is offensive to proles because it leaves them permanently on the outside looking in. If status is based on money, they might at least at some point win the lottery.

Moreover, if the lower class was actually able to figure out and adopt the aesthetic preferences and tastes of the higher class, the latter would once again feel the need to distinguish itself and move on to something else. The moment poor people started saving up all of their money and showing up at the trendiest restaurants, elites would start unironically enjoying Big Macs. If proles “learned” to enjoy postmodern art, we would see a growing appreciation for a new twenty-first century romanticist movement.

Indeed, even asking proles to participate in democratic processes on the same terms as liberal elites is seen as an insult. I have no view on string theory or quantum mechanics, because I don’t have the background to know what I’m talking about. If society tried to force me to have an opinion on these things, I might grow resentful. For people who are low on intelligence or intellectual curiosity, asking them to have a view on macroeconomic policy or NAFTA leads them to rely on base instincts. When told that those instincts are wrong, and they need to think more carefully about which policies to support, they became angry at those asking them to do something they are incapable of. A politics that plays to their most primitive emotions (“I dislike foreigners and to a lesser extent all successful people”) is the only kind they can perceive as respectful. Hence their attachment to populist figures and resentment towards elites on both the right and left, but especially the left. Liberals instinctively understand this when it comes to inner-city blacks, hence their strong resistance to lecturing that population or holding it responsible for its actions. White proles understand that for generations they have received no similar consideration, except from Trump.

For these reasons, the lower class doesn’t even try to compete on the terms set by the upper class. Without guilt, it enjoys fast food, football, Fast & Furious movies, and pornography featuring curvaceous women. Sometimes, lower class tastes are ironically the scientifically correct ones – big boobs are indeed attractive and fast food does taste good, unless you can convince yourself otherwise. Proles cling to nationalism, religion, and traditional sexual morality, the “old” value system that the upper class has moved away from. In their political and social views, as with aesthetic taste, they take the path of least resistance and have normal human morality instead of being WEIRD. Unable to discern when elites know what they’re talking about and when they don’t, proles come to distrust all of intellectual life. From their perspective, the “expert consensus” and “peer-reviewed studies” on the efficacy of covid-19 vaccines look no different from those that tell you men can get pregnant. Since you know men can’t get pregnant, why trust the vaccine?

Note that this theory is sort of the inverse of Jonathan Haidt’s idea of Moral Foundations. Although I think he’s moved a bit away from this view in recent years, in the original formulation of this theory, it is moral differences that come first and create the tribes. In my theory of the culture war, the tribes are split by class first, and then moral and aesthetic differentiation as described by Harris starts to set in. Through much of history, the higher class tended to pride itself on being less sexually promiscuous and more religious and respectful of tradition than the masses. It was only with the triumph of egalitarian ideology that it had to find more indirect ways to signal its greater intelligence and conscientiousness while pretending that it is doing no such thing.

Proles don’t have the verbal intelligence to form sophisticated-sounding rationales for what is motivating them. Elites come up with theories about what’s wrong with the masses, and write books and magazine articles explaining what is happening. Proles supposedly refuse to go along with their betters because they benefit from “white supremacy” or score high on scales of “authoritarianism.” The lower class communicates in grunts, jokes, and sigs of tribal loyalty. The upper class writes hundreds of dissertations about how even poor white people benefit from the color of their skin, while the proles have “Let’s Go Brandon!” They become obsessed with Hillary’s e-mails and Hunter Biden’s laptop because personal corruption scandals are at least simple enough for them to understand. They’re not capable of more sophisticated critiques of liberalism, and even have to rely on elites to provide them a moral framework, as when they accuse Democrats of being the real racists. The rise of QAnon is the ultimate reductio ad absurdum of this, where proles lash out by just calling everyone they resent a pedophile. Trump is their guy not because of anything he’s going to do, but because he represents the ultimate negation of the tastes and value system of the hated upper class.

Confidence level: I am more confident about what is motivating the proles than what is motivating elites because proles are much simpler and thus easier to figure out. Moreover, moral differences between classes might be more fundamental than I indicate above, but I think that the dynamics of the culture war exacerbate them.

Enter the Infinite Loop

The upper class, of course, can see all of this. The masses follow Trump. They’re anti-vaxx, anti-science, unreflective, bigoted, and closed minded. They have no taste and don’t seek to acquire any. Much of this is true, and seems to justify all of the contempt that they had for the masses in the first place. That contempt only grows, which the proles notice, and become more resentful about. Eventually, people start talking about democracy falling apart and the coming civil war. This never happens because really there isn’t all that much to fight about. The proles don’t have the equivalent of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses they can post at the entrance to Harvard, or a cause like slavery that can form the justification for a secessionist movement. Policy differences exist, but they stir relatively little emotion compared to the class resentments that are driving our divisions.

Confidence level: Pretty confident this is what is happening in the US, less so that it’s a universal characteristic of the culture war. Sometimes the culture war ends because elites simply crush the masses or the proles get distracted and go do something else. The US is unique for reasons discussed below.

Everyone Agrees on the Hierarchy

As mentioned above, proles come to distrust markers of intelligence, education, and refinement, and cling to more traditional forms of morality. Given that they have their own value system, this may lead one to ask on what basis I call the side associated with the left “upper class” and the side associated with the right “low class.” Can’t we say that to Trump’s fans, they are the elite while their opponents are the losers?

No, we can’t. A refutation of this view is found in the fact that conservatives are always going on about how liberals are “looking down” on them. When someone makes such a complaint, they are acknowledging the superior positions of their adversary. We can say that a group of toddlers or a pack of hyenas hates an adult man, but it would be bizarre to say that either of these collectives is “looking down on him.” High-status people feel contempt towards those beneath them, while the low status feel hate towards those above.

The fact that right-wing populism directs its hate towards cultural elites rather than the rich shows that the conflict is really about aesthetics and taste, and everyone agrees who has the higher position in the hierarchy. Trump tells his supporters “you are the real elite” because they’re obviously not, while the New York Times doesn’t feel the need to explicitly reassure its readers that they’re better than their political opponents. It simply shows them, through subtle reminders that they are on the side of truth and justice. The elite is capable of intellectual innovation, because as the high-status group it is the prime mover in the culture war, while its opponents react.

At its most basic level, the hierarchy separating the two sides is based on IQ. We naturally see intelligence as the quality that separates humans from animals. If you talk about the possibility of natural differences between populations in extraversion or conscientiousness, that’s extremely taboo but does not get one in as much trouble as making the same argument about IQ. Everyone understands that New York Times readers, or even Rachel Maddow viewers, have higher IQs than Sean Hannity fans. See my essay Liberals Read, Conservatives Watch TV, which explores the implications of understanding the left-right division as a matter of a literate culture competing with a pre-literate one. As I indicate there, “literate” and “pre-literate” are to a certain extent euphemisms for high and low IQ, although the distinction also encompasses traits like intellectual curiosity.

The Merchant Right and the Brahmin Left

Few people fit the prototypical profile of a member of the “upper class” or “lower class.” When it comes to the upper class, I’m thinking of say the faculty at UC-Berkeley or employees of the Ford Foundation. The lower class is probably best represented by Appalachian areas that went overwhelmingly for Trump, but it exists wherever poor and less educated people live, with the exception of black communities. Most Americans are not caricatures of one of the two main antagonistic classes, but it is the prototypes – the drag queen story reader and the January 6 warrior – that form the poles that others are attracted to or driven away from. Distaste with the other side is the main cause of rabid partisanship, and it ends up infecting even those who themselves are not close to either end of the class spectrum.

The middle class has an important role to play, and it can side with one faction or the other depending on the circumstances it finds itself in. A typical representative of this group might be a highly successful small business owner living in a suburb of a major metropolitan center. He is alienated from the left because it looks down on him for devoting his life to something as boring and small minded as fixing central heating systems instead of overcoming the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow. As with the proles, the middle class does not have the bandwith to keep up with political and artistic fashions. While the lower class can’t because it lacks the inherent intelligence to do so, the member of the middle class might be smart enough, but he is either too busy working and forming a family or not very inclined to chase status through the cultivation of certain opinions and aesthetic preferences rather than making money. At the same time, the middle class senses that the populist right is the low-status faction, and does not want to be in the same camp with them. Hence, the middle class is made up of “swing voters” who were willing to go Republican when the nominee was Romney, but moved left when the party came to be represented by Trump.

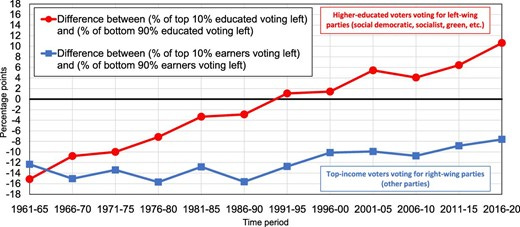

Three economists have written a paper where they note across developed democracies a natural antagonism that exists between what they call the “Brahmin Left” and the “Merchant Right.” In the early 1960s, the most educated and wealthiest citizens both voted conservative. Society was poorer, and intelligence and personality traits were more evenly distributed across the different classes. This meant less differentiation between various segments of society, and rich versus poor could therefore be the dominant divide in politics. Egalitarian ideology also hadn’t completely triumphed, so the upper class hadn’t begun shaping its opinions and aesthetics around a need to separate itself from the masses, leaving income as the dominant divide, one that caused much less bitterness.

Today, however, after the process described above, economic elites have moved slightly to the left, while educated elites have done so to a much more extreme degree.

In places where there isn’t a strong populist movement, politics now revolves around the axis of conflict between, on the one hand, an economic elite that conceives of status in terms of making money and then maybe “giving back” some of it to the community, and, on the other, an educational and cultural elite that sees status as a matter of aesthetics and morality. When populism is ascendant, however, the Brahmin Left and Merchant Right may unite against the lower class that they both find extremely distasteful.

Whether populism is a force in any particular country tends to be historically contingent. The Merchant Right and the Brahmin Left, both being composed of relatively intelligent and informed citizens, develop a kind of class consciousness no matter what, as they each have the self-awareness to naturally reflect on their position in the world and the means and inclination to participate in politics. Again, I have to stress they are not “seeking their interests” through politics; if there is a tendency to support positions that line up with their own economic interests, it is because there is a correlation between those views and what makes them feel better about themselves as individuals. Thus, rich people who made their money through commerce might support low taxes, though not because holding such views has a high expected value in monetary terms, but because self-esteem needs make them particularly inclined to believe in the virtues of the free market. The wealthy can just as easily support progressive taxation in situations where it finds populists more distasteful than the left.

Proles are naturally inclined to feel isolated from both financial and educational elites as they pursue their own hobbies and personal affairs. Nonetheless, they can sometimes be politically mobilized, though they usually need a charismatic figure. Politics usually can’t compete with the joys of NASCAR or professional wrestling unless politics itself comes to resemble prole entertainment and becomes a matter of personalities. This is why the populist movement in the US depends so heavily on the continuing good health of Donald Trump, while neither liberalism nor the mainstream conservative movement will disappear if any individual exits the scene. All over the world, we see the fate of populism being connected to a single individual or family: Trump in the US, the Le Pens in France, Nigel Farage in the UK, Orban in Hungary, etc. Relying on the political skills, luck, and vision of a single individual or family makes populism highly unstable, which is why its political fortunes vary so much over time even within the same country. It can sometimes win elections, if everything goes right, but it can’t govern.

Josh Hawley might think that if Trump retired he would be his more refined successor, but if the latter did exit the scene it is unlikely that anyone would pop up to excite the same fanbase. Once Trump is gone, the tendency will be for the GOP to revert back to normal Republican positions and electoral strategies. The Daily Beast once said that Hawley was dangerous because he’s “Trump without the stupidity or incompetence or personal obnoxiousness or open racism.” This is sort of like calling someone “the next Michael Jordan without the ability to run, shoot, jump, or play defense.” Josh Hawley might think he can figure out how to manipulate the Republican base because he has 45 IQ points over them, but when it comes to reading other people, they’re his approximate equals.

Yet while the Merchant Right is a major force in elections and even governing, it is not one of the major participants in the culture war. This is because the true antagonism is between the upper and lower classes. The middle class (in many cases, the wealthiest class), has more money than the lower class, but its entire identity does not revolve around feeling morally superior to or lecturing the latter. Not being reformers, they just want to be left alone. This stops them from being too angry at either the urban elite or the proles, which prevents the cycle of mutual hostility from starting. Moreover, the two natural elite classes, being of similar levels of intelligence, have more in common with each other than either has with the proles. They socialize and intermarry, and the boundaries between them are more fluid.

Twenty years ago, the Merchant Right was at the heart of the Republican Party, which reflected its tastes, aesthetics, preferences, and values. With the Trump revolution, they’re on the outside looking in, not entirety at home in either of the two major coalitions, ready to swing elections in one direction or the other and still governing and influencing policy when Republicans get in office.

American Exceptionalism

The culture war described above exists to a greater or lesser degree across the West. The US is distinguished because its culture war involves greater antagonism and dominates much more of public life. There are three reasons for this. First of all, the US crime rate is off the charts. In 2020, our murder rate was 6.3 per 100,000, which is around twice as high as the most violent countries in the EU. If you compare the US to some of the wealthiest states in Europe, its murder rate is at least five times higher than the UK, Germany, Sweden, or France. While much of this can be attributed to having a large black population, even our whites are unusually violent. West Virginia is about 90% white, and it has a much higher murder rate than any European country. The same goes for many other states without a lot of black people, including Kentucky, Alaska, Montana, and South Dakota. When you look at crimes other than murder, the US doesn’t look so bad, but frankly I don’t trust that data. If you believe official numbers, Sweden has a higher rate of rape than almost any country in Africa or Latin America, which is too absurd to believe, and likely reflects how statistics are collected and reported. A robbery is much less likely to be reported to the police in a violent American inner city than it would be in Japan, where crime is almost non-existent. Murder is the only good measure of violence we have, since it always comes to the attention of authorities and there aren’t many questions about how you define the crime. In addition to being disposed towards violent crime, the poor in the United States rank high on many other kinds of dysfunctions – including obesity and drug use – which makes them particularly likely to be unpleasant neighbors and increases the natural tendency for people with means to move away from them. It’s difficult to explain to non-Americans the extent to which parents here have to work hard in order to get their kids into “good schools,” which can usually mean no more than places where they’re least likely to get sexually assaulted or beaten up.

Relatedly, the American race situation makes our elites cling particularly strongly to egalitarian explanations of class inequality. The worry is that if we say some individuals and classes are smarter than others, it might imply that some races are too. In fact, the entire civil rights regime has developed around the idea that it’s illegitimate to believe that some groups are smarter or more competent. We of course can’t have a German-style system where kids of limited academic ability are directed towards vocational training instead of going to college. Because of our bizarre racial hangups, American elites feel the need to insult proles by telling them they could all be astrophysicists if they only worked hard enough. While Paige Harden can write books arguing that accepting individual genetic differences in IQ does not mean you have to abandon the idea that race gaps are completely environmental in origin, the point is too subtle for most people to accept.

Finally, America is more democratic than other developed countries. This goes against an emerging conventional wisdom in political science that has come to define democracy as “whatever liberals want.” Yet if you define democracy as respect for free speech and local control, we do pretty well. The World Bank collects metrics on decentralization and finds that compared to most other developed countries, the US grants a high degree of authority to state and local governments. While certain countries could impose national mask mandates or make education policy from the capital, our federal government is much more limited in its role. We also have the First Amendment. In other countries, one way the elite wins the culture war is to silence its opposition. Thus, European countries arrest people for speech that is racist or anti-vaccine. They sometimes put restrictions on the media that would be unthinkable in the American context, like how French law bans certain kinds of political coverage in the days leading up to an election. We also have fewer restrictions on campaign finance, which gives the lower classes a fighting chance, since proles can become rich but they can never make their way through elite institutions, which they would need to do in order to have influence in most Western European countries.

For there to truly be a culture war, you need some level of parity between the sides. The American system allows for that. The elites resent this, and draw up graphs proving that in fact Europe is more democratic than the United States since over there elites get to decide everything. Again, they call this “political science.” Liberals are on stronger grounds when they criticize the Senate and electoral college for being undemocratic, and even here the results provide more advantages to the proles relative to other nations.

Relationships to Other Theories and Closing Thoughts

It almost goes without saying that the model presented here paints a simplified picture of reality. One can accept certain parts of it while rejecting others. Whenever one presents a theory like this, it is natural to ask how it relates to other ideas, and whether it considers them overrated or underrated in trying to explain the culture war. That is the main purpose of this section. Grand theories about societal development are rarely completely true or false. Rather, they can usually only do a better or worse job of describing reality.

Class interest theories are massively overrated. I think people like economic theories because they have “physics envy.” You can measure economic outputs more directly than people’s psychological states, so it seems more scientific to rely on the former. This is part of the appeal of Marxism, which tells you everything is just at its heart class interest. It’s not that material interests aren’t real, only that it makes no sense to rely on them in order to explain mass opinion, for reasons discussed above. I actually think economic incentives are an underrated factor in explaining human behavior as a general matter. They’re just practically useless for explaining elections or voter sentiment.

Economic factors as indirect drivers of change are underrated. Few stop to consider how much wealthier we are than we have been in the recent past, or how much this contributes to class differentiation. This is not because classes develop a consciousness in the Marxist sense, but because it leads to more alienation between them. So economic forces are overrated with regards to explaining individual opinions, but underrated with regards to shaping societal forces more generally.

Moral theories are somewhat overrated. I never get tired of pointing to this paper, which has many fewer citations than Haidt’s book on Moral Foundations but in my opinion convincingly refutes its arguments about what is the major driver of our political divisions. Something like Moral Foundations is more useful than economic theories, but less useful than most people think.

Tribalism is underrated. People understand tribalism as important, but tend to think that tribal feelings are based on some underlying reality, like moral differences, economic inequality, or racial conflict. In contrast, this theory sees tribalism as the default mode of engaging in politics, and holds that it shapes how we conceive of ourselves in terms of morality, socioeconomic status, and even racial background and national identity.

Cycles of resentment are underrated. Because of the importance of tribalism, one cannot understand the right or the left in isolation. Each political movement is in part a reaction to an outgroup. Many conservatives supported Trump because they hated what the left had become and wanted to make that as clear as possible. In response, Trump made the left even crazier, and now the right has responded to that by welcoming anti-vaxx and QAnon into their coalition. Not enough consideration is given to the possibility that by fighting back against your opponents by embracing the worst people on your side, you make your adversaries into even worse versions of themselves. I grant that the cycle of resentment might have gone so far that it wouldn’t make sense for either side to pull back now, so trying to crush your opponents with whatever means you have might be a rational strategy.

Luxury beliefs is correctly rated. Rob Henderson is right to emphasize the importance of status as a driver of political attitudes. I get uncomfortable though when some people suggest that rich people hold the views they do because they don’t suffer the consequences of their beliefs, which has the same problem as economic theories of voting discussed above. Nonetheless, he gets a lot of credit for placing status at the center of his understanding of politics.

As for predictions, this theory argues that we will continue to hate each other, but, as I’ve recently noted, American democracy is safe, and the system is extremely stable. It’s not because elites pacify the masses through bread and circuses, but because in the end this is all just entertainment, and most real policy accomplishments are achieved far from public view. Good people with legitimate concerns sometimes do hang on to one of the main coalitions and try to move policy in their preferred direction, but the level of anger remains relatively constant at both ends of the political spectrum. None of this is to say that the culture war doesn’t touch on some serious issues. Yet when it does, it is usually by accident, as the psychological concerns driving the process are mostly petty and trivial. The culture war as such will not be won or lost, as it is not about deep philosophical differences regarding the good life, but the product of unhappy people seeking status at the expense of others, and the tribes that form around the great antagonists in this battle.

No comments:

Post a Comment