Tamir Hayman Ofer Shelah

If I am put in a position of being asked to execute something I feel is immoral, unethical, or illegal, I believe I have only one option, and that is to make my point extremely forcefully and then, if I am unable to reconcile that difference simply to resign.[1]

Admiral Stansfield Turner, former head of the CIA

Leading a security establishment demands strength and the ability to withstand various types of significant pressure. One such pressure is the need to remain in office even in difficult circumstances, in order to ensure the system’s stability and to show the rank and file that leadership means continuing to remain at the helm and not abandoning the job. Therefore, resignations by senior command figures are rare. Nonetheless, is there a situation in which a commander must resign? Are there in fact cases where remaining in a position of command is unethical? These questions are not posed in a vacuum, of course. At the time of this writing, the reality is Israel is complex, and the tension between the political echelon and the operational echelon is unprecedented, as shown by the dismissal of Defense Minister Yoav Gallant (which was later rescinded), after he expressed the concerns of military commanders regarding the IDF’s ability to function. This article presents professional rules with reference to this weighty issue, based on an analysis of past cases. Although the scope of the examples is limited and the future event, if it materializes, will be singular in nature, there are cases, in Israel and elsewhere, from which lessons can be learned.

Lessons from the Past

Reasons for past resignations by senior officials can be divided into a number of categories: resignation for personal reasons, following the exposure of an event linked to conduct that arouses serious criticism, which is not relevant to the current discussion; resignation due to taking responsibility for the organization’s performance; resignation or retirement due to professional disagreements; resignation based on a sense that the political level is endangering the country or the security organization.

Responsibility for the Organization’s Performance

Of the three IDF Chiefs of Staff who resigned, two did so following criticism of the army’s performance and their own conduct in wartime – the late Lt. Gen. David Elazar following the Agranat Commission report in 1974 about the Yom Kippur War, and Lt. Gen. Dan Halutz when in his words he had “fulfilled his responsibility” following the Second Lebanon War. These resignations are similar in nature to the resignation of then-head of the GSS Carmi Gillon after the murder of Yitzhak Rabin (1996), and the resignation of the head of the Mossad Danny Yatom after the attempted assassination of Khaled Mashal and the report of the Ciechanover Committee of Inquiry (1998). In these cases, the officers took public responsibility, but did not resign over differences of opinion with their superiors.

Disagreements over Policy

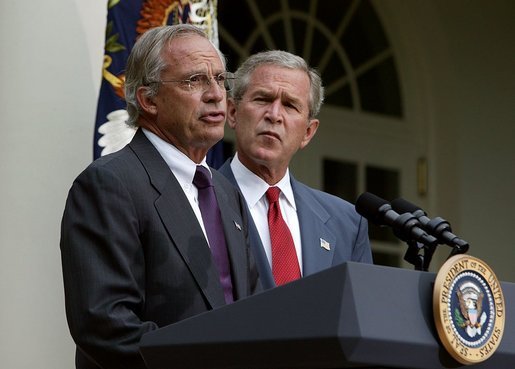

In 2006, CIA Director Porter Goss resigned after less than two years in office. No official reasons were given, but several reports linked the resignation to profound disagreement with John Negroponte, who was appointed by President Bush to the post of Director of National Intelligence (DNI), a new agency with powers over more than 17 United States intelligence organizations, including the CIA. The new framework came in the wake of the lessons learned from the intelligence failures before the disastrous attack on the Twin Towers on 9/11 (2001).

Other known cases involve severe criticism by serving personnel of policy dictated by the political level, which occasionally ended in resignations, when the officials decided not to continue their security career. Paul Eaton and John Batiste, both two-star generals (equivalent to the IDF rank of major general) who served in Iraq after the US invasion of 2003, chose not to continue in the military, although they were candidates for promotion, and after their resignations strongly criticized the policies of then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.[2]

In these cases, the retiring commander acknowledges the seniority of the political level, exercises his responsibility by disputing policy, and retires when he is personally unable to perform his job but does not claim that the policy shatters the ethos on which the organization rests or its ability to function.

A Sense that the Political Echelon is Endangering the Country or the Security Organization

This category is particularly relevant to the current crisis in Israel, since senior officials are apt to find themselves facing one of two extreme situations:

Legislation that undermines the regime order in Israel, and could even lead to a constitutional crisis, where there is a conflict between political decisions and judicial rulings. Such a situation would be damaging to the value of “stateliness” (mamlachtiut), which was added as a basic value by then-Chief of Staff Aviv Kochavi to the IDF ethical code,[3] which stipulates that the IDF is subordinate to “the authority of the democratic civilian government and the laws of the state.” This formulation places the law, whose interpretation is under the jurisdiction of the courts, side by side with the government, as the fundamental entities to which the IDF owes allegiance. It shows the full gravity of the essential problem that could arise when there is a conflict between political decisions and judicial rulings. Nadav Argaman, the previous head of the GSS, referred to this possibility when he warned against the massive departure of people serving in security organizations “if the State of Israel should stand on the brink of dictatorship,” at which point “we can see the internal collapse of the system’s organizations.”

A situation where ability of the organization to fulfill its role, and even its basic character (the IDF as the people’s army) is at risk. Continuation of the processes resulting from moves to promote the judicial overhaul by the governing coalition and the protests against them – implementation of the threat by thousands of reservists not to report for duty, or severe damage to IDF recruitment due to the introduction of the Basic Law: Torah Study – could bring the IDF to a situation where it would be unable to perform its missions. Warnings of such an outcome have already been voiced by retired senior personnel, as well as, anonymously, by members of General HQ.[4]

There is a recent parallel with the first situation: in June 2020 there was an unprecedented clash between the United States President Donald Trump and General Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Trump ordered Milley to use units from the US Army and the National Guard against demonstrators in Washington, D.C. who were protesting the killing of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis. At the height of the argument, according to a report from a reliable journalist, the President shouted at the commander of the military: “Can’t you just shoot them? Just shoot them in the legs or something?”[5]

This interchange and similar incidents led the supreme commander of the United States military to think about leaving his job, and he even drafted a letter of resignation, which is fully quoted in that report. Milley accused Trump of politicizing the army; of attempting to sow fear in the hearts of US citizens when it is the function of the army to protect them; of acting contrary to the basic value of equality, irrespective of religion, race, or sex, which is the heart of the US constitution; and of destroying the international order – causing huge global damage to the United States. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff ended his letter with these words: “You subscribe to many of the principles that we fought against. And I cannot be a party to that. It is with deep regret that I hereby submit my letter of resignation."[6]

Ultimately, and after consultation with his immediate predecessor, General Joseph Dunford, and others, Milley decided to remain in his job. He set himself four objectives: to ensure that the President would not launch an unnecessary war overseas; to prevent Trump from using the military against US citizens on US streets; to ensure the wholeness of the military; and to maintain its integrity.[7] In the ensuing months both he and Secretary of Defense Mark Esper claimed to have played a decisive role in preventing dangerous moves that the President wanted to carry out in the last days of his term of office.[8]

In this case, Milley acted as would be expected of a commander who receives a patently illegal order: it is clear he must not obey it, but he must also remain in his post in order to ensure that the order is not obeyed, since it could be implemented by whoever assumes command following his resignation. His ethical obligation is to remain in his position, to back up his troops who disobey the order, and if necessary to pay the necessary personal price – dismissal. This was General Milley’s decision, and this is the conduct to be expected from the heads of security organizations in the event of a constitutional crisis.

The second situation – the danger of the collapse of the IDF human resources structure and its ability to perform its tasks in view of the response to legislation passed by the government among conscripts, soldiers in the regular army, and reservists – has a parallel in the IDF from seventy years ago. Yigael Yadin, the second IDF Chief of Staff, resigned following a strong disagreement with Prime Minister and Defense Minister David Ben-Gurion over the size of the budget for the army, which was in essence was rebuilt after the War of Independence.

According to historian Mordechai Bar-On, Yadin consistently exceeded the approved IDF personnel levels and demanded additional budgets, in spite of the severe economic crisis of those years and Ben-Gurion’s unequivocal demands to reduce the number of people in the regular army and civilians employed by the IDF.[9] Yadin warned that the military would be unfit for purpose, demanded that compulsory service be extended to two and a half years, and ignored the Treasury’s demands for cuts, leading to a crisis and a halting to the flow of funds to the IDF by the Finance Ministry – a move that left the IDF effectively insolvent. Ultimately, in December 1952, Yadin resigned.[10] (Four years previously, Yadin had been involved in a no less dramatic event – “the Generals’ Revolt”, at the height of the War of Independence, but this did not involve a similar dilemma.)

Yadin chose to resign, after reaching the conclusion that with the budget imposed on him by the political level, he could not ensure an army that was able to fulfill its tasks. His decision is similar to that of a commander who feels that he is unable to implement a legal order from his superiors. In this case, the commander must warn that he is unable to perform his duty, and if the command remains in force, he must resign.

The Importance of Warning the Political Echelon

When a senior commander considers resigning due to a crisis of trust with his superiors, or a mortal blow to the ethos on which the organization rests, or a sense that a situation has arisen that prevents him from performing his tasks and the organization from fulfilling its purpose, there is a heavy price to pay. It is proper and even mandatory to discuss this possibility before it becomes a reality.

In a situation of a constitutional crisis, the Chief of Staff – like the leader of any national security organization – must stress to the politicians the serious and material problems it entails: he must clarify that the army must not be placed in a situation where it has to choose which of the authorities to obey, and that as a citizen of the country he will act and command solely in accordance with its law. Even in the second situation, in which government’s policy and the citizens’ response cause serious damage to the military, making it unable to fulfill its tasks, the Chief of Staff (or head of any other security organization) must present the situation to the political echelon in its full gravity. If matters can be settled behind closed doors, even in a one-on-one discussion, there will be no threat and it may be possible to avoid extreme situations.

The IDF is the people’s army, and it has the obligation to defend the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state. It is subordinate to the political echelon and acts in accordance with the law and the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. Such a clarification is required at the present time, and should be the basis of a discussion between the political level and the military level about the limits of authority and the red lines that govern the commanders and the organization.

The commanders of the principal security entities in Israel should already initiate the required discussions.

No comments:

Post a Comment