Daniel Sukman, is a U.S. Army Strategist. These views do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Two hundred years ago, Napoleon suffered his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. Up until that moment, Napoleon revolutionized warfare in his operational approach to battle. Clausewitz would follow the Napoleonic wars with his seminal writing On War, in which he described the science of warfare. Just as influential, Baron Jomini would take the lessons he learned while fighting under Napoleon and translate them into Principles of Warfare. These principles, published in Precis de l’art de la guerre (The Art of War)included maxims such as focusing an attack on a decisive point and the ability “ to quickly maneuver and engage fractions of the enemy’s army with the majority of one’s own.” These principles are applicable to warfare today as they were two centuries ago.

Two hundred years ago, Napoleon suffered his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. Up until that moment, Napoleon revolutionized warfare in his operational approach to battle. Clausewitz would follow the Napoleonic wars with his seminal writing On War, in which he described the science of warfare. Just as influential, Baron Jomini would take the lessons he learned while fighting under Napoleon and translate them into Principles of Warfare. These principles, published in Precis de l’art de la guerre (The Art of War)included maxims such as focusing an attack on a decisive point and the ability “ to quickly maneuver and engage fractions of the enemy’s army with the majority of one’s own.” These principles are applicable to warfare today as they were two centuries ago.

In a contemporary context, watching Michigan’s collapse against the Spartansof Michigan State, and the failed fake punt of the Indianapolis Colts, makes one think of how the modern principles of warfare can be applied to the gridiron. I offer the principles of warfare as a method to design a higher echelon of strategy vis-a-vis the game of football.

Baron Jomini

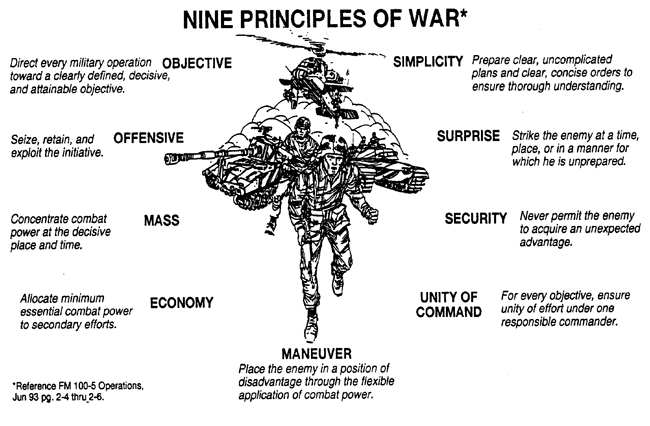

Today, joint U.S. military doctrine recognizes nine principles of war which include the following:

Objective: To direct every military operation toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective. Examples of a clearly defined military objective include defeating an enemy force, seizing a key piece of terrain. When a militarily force is unclear on what its respective objective is on the battlefield, chaos ensues. Arguably, following the fall of Baghdad, the U.S. military failed to establish a clearly defined objective for forces in Iraq leading to years of strategic wandering. Certainly, every football team begins the season with a clearly defined objective, to win a championship. However, when that objective falls to the wayside early in the season, or when a team enters a season understanding that a championship is a step to far, head coaches and general managers often attempt to change the objective. Often head coaches will term the objective as “rebuilding.” It’s a false method of hope, when a football team has an objective of rebuilding in lieu of victory, chaos in the organization ensues.

Offensive: To seize, retain, and exploit the initiative. Clausewitz wrote that defense is the strongest form of warfare. However, the American way of warfare remains offensively focused with the understanding that you can’t win a war without eventually attacking your enemy. The National Football League has seen an evolution of conflict between the strongest forms of football. From the time the New York Football Giants responded to the Joe Montana led San Francisco 49ers with a defense led by Lawrence Taylor and Jim Burt. Further evolution of the conflict pitted defensive juggernauts such as the 1985 Chicago Bears, 1990 New York Giants, and 2013 Seattle Seahawks pitted against the offensive teams such as the 1980s San Francisco 49ers, 1990s Buffalo Bills, and the recent 2014 New England Patriots. Although the pendulum swings back and forth between offense and defense, the evolution of the game, and its respective rules governing the sport favor the offensive attack.

Mass: To concentrate the effects of combat power at the place and time to achieve decisive results. Ensuring sufficient combat power for all phases of an operation is a hard lesson learned from the past 15 years of combat. Arguably, leaders such as General Shinseki understood this principle when testifying that an occupation of Iraq would require a couple hundred thousand boots on the ground. In the tactical realm, the ability to outnumber an opponent, either on the offensive line to attack the quarterback, or maneuvering offensive lineman to where the football will be on a screen or bubble pass is a fundamental concept.

We should have listened

We should have listened

Economy of Force: To allocate minimum essential combat power to secondary efforts. In military operations, most commanders identify a main effort and supporting efforts. The main effort thus receives priority for intelligence, logistics and fires support. At the operational level, an economy of force was in display with the invasion of Iraq. In 2003, the bulk of U.S. combat forces executed a rapid assault on Baghdad. Other cities in Iraq such as Basra required attention and military operations to secure initial victory, however, as a secondary effort limited capabilities were applied to secure the city. In the era of the salary cap, professional football organizations must determine how to spend their money on top talent, and balance risk with the acquisition of lesser talent.

Maneuver: To place the enemy in a position of disadvantage through the flexible application of combat power. In designing operations or strategy, a commander looks to keep his force in key positions on the battlefield. From the time the Continental Army took Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston, to the Left Hook of the Gulf War, proper maneuver on the battlefield can be decisive to victory. Maintaining a relative advantage in field position is one aspect of maneuver. If a team can not score on every possession, they should continue to place the opposing team in a position of disadvantage by having them start an offensive series deep in their own territory.

Unity of Command: To ensure unity of effort under one responsible commander for every objective. The best military plans and operations occur under the unified direction and command of a single commander. When military forces operate under separate commands, often the result is operations occurring within a cylinder of excellence. Actions then occur on the battlefield that is either duplicative or conflicting in nature. Indeed, one of the inherent strengths of how the U.S. military fights is through a single Joint Force Commander in lieu of separate service commanders for a given operation. In terms of football, the best run organizations are those with a continuity from the owner, through the general manager, to the head coach and down to the players on the field. Picture the organizations such as the Pittsburgh Steelers and New England Patriots who have maintained a level of long term success. The two best examples of unity of command in professional football are the early 1990s Dallas Cowboys under Jerry Jones and Jimmy Johnson, where the players drafted and acquired fit neatly into the system of the head coach. Today, unity of command is on full display with the New England Patriots, where the acquisition of talent matches the designs of the head coach.

Security: To never permit the enemy to acquire unexpected advantage. Security is paramount to any military force. At the tactical level, the ability to avoid maneuvering into an ambush. At the strategic level, the capacity to protect forces to avoid the disastrous effects of a suicide bomber as seen in Beirut in 1983. In modern warfare, commanders consistently evaluate the security measures of the force within any given operation, from missile defense over an airfield to the convoy security measures taken on the roads in Iraq. We see security translated to the football field in the design of a solid defensive scheme. Further, teams consistently take caution on special teams so not to be surprised with a fake punt, fake field goal, or unexpected onside kick. Further security lies in the capacity of the offensive line to protect a star quarterback. Michael Lewis, in his book The Blind Side, detailed the value of the Left Tackle position in how teams place emphasis to ensure the center of gravity of a team stays healthy. One team can quickly gain an advantage over another by knocking a quarterback out of the game.

Surprise: To strike the enemy at a time or place or Ina manner for which it is unprepared. In terms of military operations, two historical examples come to mind. First, the 1991 “Left Hook” executed by U.S. ground forces in the liberation of Kuwait. Saddam Hussein expected an amphibious assault. As the air campaign begun, and his regimes ability to monitor U.S. forces disappeared, resulting in a movement of forces to posture for an offensive at an unexpected location behind the Republican Guard. In terms of football, teams look to achieve surprise through game planning, and the study of an adversary in the week prior may lead to a surprise tactic in the course of a game. More than a single gadget play, achieving surprise on an opponent may include creating a mismatch on the offensive or defensive line, or using a ground attack when a team is known for its passing game.

The Famous Left Hook of Operation DESERT STORM

The Famous Left Hook of Operation DESERT STORM

Simplicity: To prepare clear, uncomplicated plans and concise orders to ensure thorough understanding. Violating the principle of simplicity in warfare creates conditions where commanders on the battlefield may be unclear of a higher commander’s intent or scheme of maneuver. War is the most complex of human activities, and overly complex strategies are almost all destined to fail. We watched this event play out on the football field with the disastrous fake punt in Indianapolis. Not only did the Colts have no clue on how to execute the play, had they been successful they still lined up in an illegal formation. Over complicated trick plays, or offensive and defensive schemes rarely work in the long run.

Moving from the science of strategy to the art, a strategist must understand when to sacrifice one principle of warfare to achieve another. For example, to achieve surprise on the battlefield may require taking risk in the ability to mass forces. The Doolittle Raid over Tokyo in WWII serves as an example. Taking extreme risk to achieve a level of surprise meant minimal forces applied to the raid. Looking at the art of strategy on the football field, a head coach may do the same when calling for a bootleg with the quarterback. Fewer players blocking for the ball carrier, but more yards gained due to achieving surprise on the defense.

I offer these principles as a method to think about strategy outside the realm of warfare. Establishing strategic principles to guide strategy, be it on the battlefield or the football field is paramount to strategic success.

The Enduring Principles of Warfare

The Enduring Principles of Warfare

No comments:

Post a Comment