Inbal Orpaz, David Siman-Tov

In addition to the fighting between Israel and Hamas and the clashes in Israeli cities with mixed Arab and Jewish populations, Operation Guardian of the Walls unfolded on a complementary arena – that of social media. Events in this arena affect Israeli and Palestinian cognition, as well as that of the global public. It is difficult to analyze the impact created in this arena, since it involves Israeli, Palestinian, and many other elements, and it is often impossible to know who is behind which developments and to understand the interests of the respective actors. Nonetheless, it is evident that during the campaign, social media activity helped reinforce the fear of Hamas among the Israeli civilian population and aroused criticism of the operation, domestically and worldwide.

This article surveys various aspects of the social media digital arena during Operation Guardian of the Walls, and shows how messages are conveyed to different target audiences by means of both true and fake news. Warfare in the digital arena includes online developments, particularly on social media, and virtual events that influence cognition (unlike cyberattacks, for example). That social media activity continued even after the IDF and Hamas stopped firing is one of the features that distinguish this arena from warfare in the kinetic arena. There was also a largely covert cyber campaign, although this article does refer to a number of exposed cyberattacks that were intended to influence the online discourse.

The analysis leads to the following conclusions and recommendations: Israel should strengthen “readiness on the home front” to withstand social media efforts to exert influence, by means of education to improve the public’s digital literacy skills. It should also examine how it provides information and presents its case, with the right mix of offense and defense. The Israeli public and its supporters worldwide that seek to promote Israel’s position on social media should be assisted with an infrastructure to provide credible data and relevant messages; it is also important to promote legislation and means of enforcement so that the authorities can intervene in events in digital arenas where necessary, particularly in order to prevent outbreaks of violence. Finally, there is a need to create channels of communication and procedures for working with social media platforms to remove violent and inciting content and prevent foreign intervention.

The Digital Arena on Social Media during Guardian of the Walls

The digital arena comprises a range of channels and platforms, which change over time in response to technological developments. Prominent platforms that were popular during Operation Guardian of the Walls include Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram. A growing platform that became vital for conveying information during the campaign was TikTok.

Due to the decentralized nature of social media, messages – including fake news – can spread rapidly and even uncontrollably, and it is hard to repair the damage they cause. Messages go viral, among other reasons, because they act on strong emotions such as fear, which drives users to continue spreading them. As in previous conflicts, and thanks to the growing popularity of Instagram, TikTok, and Telegram, social media provided space for senses of victory or loss on both sides, and enabled people all over the world to feel they were participating in events.

One reason why it is so hard to monitor these arenas is that many messages are disseminated between individuals or in closed groups. The state is dependent on the interests of companies such as Facebook or Twitter, since they alone have the power to remove content from their channels or to block accounts. Indeed, even before the ceasefire, Facebook blocked some WhatsApp accounts of activists identified with the Israeli right wing organization Lehava. Facebook did not publicize the reasons for blocking the accounts, but the step was taken a few days after Lehava activists were involved in violent incidents in Israeli cities with Jewish and Arab populations, which were partly organized by WhatsApp groups.[1]

The content distributed in the context of Guardian of the Walls in social media was varied: photographs taken during the fighting, shared infographics that stressed, for example, statistical data relevant to the conflict,[2] comments by social media influencers on videos, and other content expressing solidarity with one of the parties to the hostilities, for example TikTok users who painted maps of Palestine on their faces.

A central typical pattern during the campaign revolved around efforts to influence public awareness by spreading disinformation, particularly by taking pictures and videos out of context. All parties made use, sometimes not intended, of inaccurate or deliberately false information, as a means of arousing strong feelings – one of the mechanisms on which fake news is built (figure 1).

Left: Vandalized and desecrated synagogue in Jerusalem, January 29, 2019 | Right: Osnat Mark, former MK: This is neither Kristallnacht, nor the 1929 riots. This is Lod, 2021. This evil must be eradicated before it blows up n out faces. This is what happens when the enemy sees a weak hateful government formed that relies on the votes of those who pursue insanity.

Figure 1. Original images used out of context during the operation

In this article, the principal digital arenas on social media are categorized by target audiences and intended purposes: the fighting between Israel and Hamas, violent events in Israeli cities, public opinion in the Arab and Muslim world, and international public opinion.

The Difficulty of Measuring Impact in the Digital Arena

A central challenge posed by the digital arena is the difficulty of assessing the influence of the occurrences and developments in the theater. In some cases, there is a clear effect, when messages in the digital arena translate actual physical incidents – for example, violent events organized on WhatsApp and Telegram groups, which caused actual human casualties and damage to property. Another example was the case of individuals and organizations that sent employees home early due to fears of a Hamas attack at a specific time created by false viral messages.

However, in most cases it is hard to assess actual influence. For example, how and to what extent was Hamas affected when its internet site was brought down by the IDF? Given this difficulty, there is another dimension to the impact of events in the digital arena – how they affect perceptions and attitudes, which is complex and extremely difficult to measure in quantitative terms only. This is partly because it is difficult to separate the effect of digital events from other factors that influence cognition, such as the traditional media. An influencer’s post about the operation can be measured by the number of exposures, shares, likes, and other engagement indicators, but this does not capture the actual impact of the post.

So it is possible to wonder what – if anything – was the effect of the network exposure to fake posts by the “desperate Israelis” Twitter network to hundreds of millions of followers in the Arab world. Because contrary to events in the physical arena during a campaign, where it is possible to give clear data (number of dead, injured, direct hits on buildings), it is much harder to assess the results of events in the virtual arena. However, in view of the wide exposure of social media posts, the rise in antisemitic incidents, and the way that social media posts seep through to traditional media and the public discourse, it would be wrong to underestimate their impact at the national level.

First Arena: The Struggle between Israel and Hamas

The central conflict in Guardian of the Walls was between Israel and Hamas, starting with the rockets fired by Hamas toward Jerusalem on May 10, 2021. This was also the central arena for social media, and official elements such as spokespeople for the IDF and the military wing of Hamas were very active in these realms. For example, Mohammed Deif, leader of the Hamas military wing, announced Hamas military actions, such as the ultimatum to Israel – unless Hamas demands were answered, rockets would be fired at Jerusalem – using the Telegram account of his spokesman, Abu Obeida. Other Hamas military updates, such as taking responsibility for shooting, were also given through Telegram.

During the operation, IDF spokespeople were active in Hebrew, Arabic, English, and Russian, thereby reaching out to different audiences. Hebrew activity was seen on several channels, such as the Telegram group “IDF – Official Channel,” which carried direct updates from the IDF and was mainly used for updates about events; on Twitter the IDF spokesman was active on the Israel Defense Forces account. There were tweets with instructions for civilians from the Home Front Command, and reports about targeted attacks on senior Hamas figures and destruction of the tunnels in Gaza. The specific purposes of the IDF spokespeople were to strengthen Israeli public support for military action against Hamas, and to improve home front awareness of the military defense against missiles fired into Israeli territory.

Meanwhile, the IDF messaging to the Arabic audience and the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip stressed the harm that Hamas was causing to the Gaza population. There were also caricatures in Arabic, showing Hamas leaders hiding in tunnels, similar to those used in Operation Pillar of Defense and Operation Protective Edge.[3] These actions were designed to reinforce criticism of Hamas by Gaza residents and to undermine its rule. An example can be seen in warning tweets such as “Stay away from Hamas sites.”[4]

The rapid and uncontrolled spread of messages and posts – real and fake – in times of warfare can increase feelings of fear and tension on the home front. For example, during Guardian of the Walls a viral message was sent to Israel citizens, claiming that Israeli Arabs were receiving warnings about a barrage of rockets to be launched from Gaza at seven in the evening (figure 2). There was no factual basis to these messages and there was no evidence of the messages sent to Arab citizens. Nevertheless, they were widely shared and spread panic and tension as the time approached, but the rockets were not fired. It is not known who started the messages or if there was any foreign intervention that Israeli citizens unwittingly helped to spread this misinformation – the unintentional distribution of lies and deception.

Shalom everyone,

Arab residents in our country have received SMS from Gaza saying there will be a very heavy barrage of rockets at 19:00 and they should take shelter and be prepared. After a difficult night they are ready and know where to aim (if there’s doubt there’s no doubt). Take note and prepare accordingly

Figure 2. Example of a fake WhatsApp message

Other baseless rumors that were disseminated on social media referred to incidents that were banned from publication due to censorship, for example, terrorists entering kibbutzim (events that were not published in the media if they indeed happened). These cases show the limits on censorship and injunctions against publishing in the modern era; while it may be possible to prevent publication in the traditional media, information can continue to flow through digital channels where restrictions cannot be enforced. One of the most common patterns observed during Guardian of the Walls was the spread of videos or photographs that predated the campaign and sometimes referred to other places (figure 1). These actions helped sow fear in the Israeli home front and fanned the flames of hostility.

Some examples:

A video clip distributed on social media in Israel mocked the Palestinians by showing what looked like a Palestinian funeral, until an alarm siren went off and the “dead” body was seen alive. This video was originally filmed in Jordan in March 2020.[5]

A photograph of a girl from Gaza who was ostensibly injured by an IDF phosphorus attack during Guardian of the Walls. The picture was taken from an article about a girl in Afghanistan who was injured during a Taliban attack (figure 1).

During the operation, the Prime Minister’s spokesman in Arabic, Ofir Gendelman, shared videos that were allegedly from the fighting in Gaza but were actually taken on earlier dates and even in locations outside the Strip.[6]

Sometimes the deceptive messages on social media designed to influence Israeli public opinion come from the traditional media. An example from Guardian of the Walls is a Hamas video showing the launch of an anti-tank missile on an Israeli jeep. The video was broadcast by Kan 11. Later a correction was published, saying that the video dated from 2012 (figure 3).[7] This was not the first time that Hamas disseminated a misleading video: during the escalation in May 2019, Hamas published a video that purported to show an anti-tank missile landing just a few moments after an Israeli train had passed, but it emerged that there were no trains in the area on that day.[8] The video was broadcast by a number of Israeli television channels.

Kan Hadashot: Hamas documentation: anti-tank fire towards the Israeli vehicle

Ido Coren, Arab Affairs Desk, Israel Public Broadcasting Corporation : The video shown on al-Mayadeen is from 2012. A generally credible channel that is close to Hamas. This was another way of confusing the enemy, and unfortunately we fell for it

Figure 3. Anti-tank missile fired at train that was not in the area

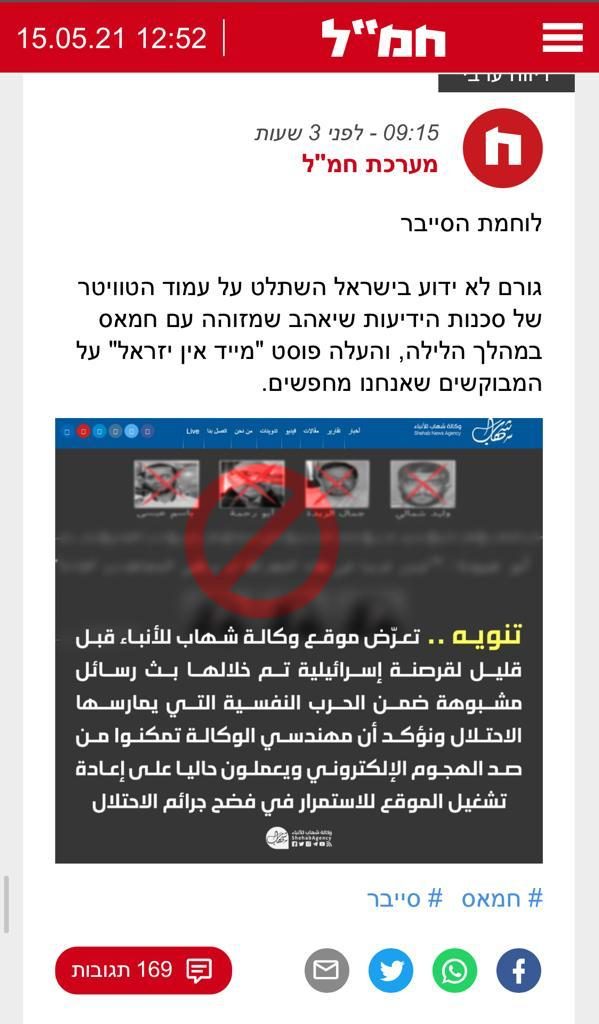

In addition to the struggle on social media, during Guardian of the Walls there were also cyber incidents linked to the efforts to influence cognition and public mood. This includes Israel’s kinetic attack on the Hamas cyber array, which hampered its digital efforts to work against Israel and wield influence through social media (figure 4).[9] It is also possible to point to cyber actions attributed to Israel that combine manipulation of content on social media, such as taking control of the Hamas website and a news agency identified with the organization, and publishing messages that support Israel or try to discredit the image of Hamas.

Cyber Warfare: An unknown element in Israel took control during the night of the Twitter page of the Shiahav news agency that is identified with Hamas, and put up a post “Made in Israel” about the wanted people we are looking for.

Figure 4. Hamas website goes down during Guardian of the Walls

Second Arena: Violent Incidents in Israeli Cities

The violent incidents in Israeli cities with Arab and Jewish populations during Operation Guardian of the Walls were also prominent in the digital arena, which became a central platform for rallying participants in such incidents. Before and during the campaign there were examples of “TikTok terror,” including attacks by Arab citizens of Israel on Jews and public property. Interesting about this phenomenon is that it combines on social media – for the first time – a social phenomenon with cultures of imitation and daring in the context of a violent popular confrontation.[10]

During the campaign, dozens of local WhatsApp and Telegram groups were formed to share information about weapons, coordinate preparations for violent incidents, and disseminate messages of incitement. Researchers from the FakeReporter platform penetrated some groups and shared their content, and also reported them to the police.[11] Some of the users were blocked and some WhatsApp and Telegram groups were removed after they were reported to the authorities.

During the operation the police issued a call to the public not to take part in the incitement on social media that leads to actions that break the law.[12] After the first days of violence in the streets of cities with mixed populations, the police and the GSS took steps to isolate groups that according to media reports organized the attacks, but the violent messages were not blocked – although there was a decline in the disturbances after the first days of the operation.

In addition to their use to organize and coordinate violent incidents in Israeli cities woyj Kewish and Arab populations, digital networks were used to spread disinformation intended to create panic and raise the level of fear in the general public. For example, Facebook groups of Ramat Gan residents posted items from activists identified with the right wing organization Lahava, in which they claimed that Arabs were knocking on doors or trying to seize vehicles in the streets – events that Mayor Carmel Shama Hacohen called “fake news” on his Facebook page.[13] In addition, a few days after the ceasefire came into force, it was announced that Facebook-owned WhatsApp had blocked 15 accounts identified with 15 activists of the Otzma Yehudit party who were involved in organizing violent incidents in Israeli cities. In this arena as well, use was made of photographs that were taken out of context. Former MK Osnat Mark tweeted on the violent incidents in Lod[14] – but misleadingly used a picture from a vandalized synagogue in Jerusalem in 2019 (figure 1).[15]

Third Arena: Public Opinion in the Arab and Muslim World

Events in the Gaza Strip and in mixed-population Israeli cities during Operation Guardian of the Walls were widely publicized in the Arab world through social media. Hamas used them as a central channel for conveying the Palestinian narrative to the global public in general, and to the Arab public in particular, with the aim of presenting Israel as weak and glorifying Hamas. In these cases, although the messages were not aimed at the Israeli public, they attracted interest in Israel since they influenced both the way Israel was perceived during the operation and its international legitimacy to continue fighting. Some of the network content was directed at residents of the West Bank and intended to incite them against the Palestinian Authority in the sensitive period following its postponement of elections.

An example of a pro-Palestinian influence campaign aimed at Arab public opinion included opening hundreds of Twitter accounts with fake Hebrew names, which tweeted in Hebrew about the intention to leave Israel and false reports about the number of Israeli casualties. The FakeReporter research platform mapped some 300 of these accounts that were closed by Twitter. Social media influencers in the Arab world subsequently posted screenshots of posts that received wide exposure. For example, a Facebook post from the Algerian journalist Hafid Derradji on this subject received over 130,000 likes and reached more than 23,000 shares. In the estimate of FakeReporter, about 100 million people in the Arab world were exposed to such posts on Facebook alone.[16]

It is not known who was behind this network, which did not have much effect on the Israeli public, who were easily able to identify the accounts as fake by the poor level of Hebrew, but it did strengthen the image of Hamas in the Arab world. Although the users pretended to be Israelis, their target audience was in fact Arab speakers. The nature of the activity showed that it was a front for an organized entity that could easily run similar operations in the future or continue with the same systems from before this campaign.

This example illustrates the potential effect of coordinated inauthentic behavior of fake accounts pretending to belong to Israelis, and there are others. It raises questions about who is behind these campaigns. Who contacted influencers in the Arab world and drew their attention to the allegedly Israeli accounts? Did the Arab influencers know that they were sharing false content or that they were being misled? And what is the best defense against such disguised attacks, particularly during emergencies?

TikTok, a growing social network based on video sharing, likewise played a central role in the Palestinian campaign designed to influence how Hamas is perceived by both global and Arab audiences. During Guardian of the Walls, the TikTok videos also reached an Israeli audience, with content designed to cause demoralization. TikTok videos bearing the hashtag #gazaunderattack attracted over 325 million views during the fighting, while videos with the hashtag #israelunderattack reached only 20 million views. Examples of fake videos were also found on TikTok, such as a video showing rocket launches from a mountainous coastline that were labeled as showing launches from Gaza into Israel, while the video actually originated in Taiwan in 2018. Another example is a TikTok account pretending to represent soccer player Cristiano Ronaldo, which began posting content in April 2021 and reached about half a million followers. One half of the screen in the videos shows the athlete, while other half shows images designed to promote Hamas messages, for example, burning Israeli flags (figure 5). Every video posted by the account attracts hundreds of thousands of views.

Figure 5. Would- be Cristiano Ronaldo TikTok account

In the attempt to influence Arab public opinion during the operation while reinforcing Israel’s legitimacy, Israel was active on its official channels in the Foreign Ministry, led by the digital department, and on social media. According to sources in the Ministry, there was a considerable increase in exposure to the Ministry’s channels (Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, etc.) – up to half a billion visits during the ten days of fighting, in all the languages of their platforms, compared to 1.3 billion visits in a normal year. In addition to intensive activity on the various platforms and in a range of languages to spread messages supporting the Israeli position, the Ministry intervened at specific points, for example, in a Twitter conversation with the Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister (in view of the media storm that followed the raising of the Israeli flag over the Austrian parliament building) and with influencers who came out against Israel. The Ministry worked on having the accounts of Hamas spokesmen (such as Abu Obeida, whose account was removed) removed from Facebook and Twitter. In the international arena, the Foreign Ministry helped Israeli, Jewish, and Israel-supporting influencers develop and publish relevant content.

The IDF’s Arabic-language spokesman, Lt. Col. Avichay Adraee, was active on various social media channels from his private profile.[17] During the operation, his activity focused on two targets – the Arab public worldwide, and the public in Gaza. In both cases, Adraee made efforts to introduce terminology that suited the Israeli perspective, such as “the jihad hotels” – referring to Hamas leaders who had abandoned their people and were sitting out the fighting in hotels in the Gulf states, and the “Hamas mistake,” an expression that was first used in 2006 after the Second Lebanon War with Hezbollah, hinting that attacking Israel was a mistake.[18]

Moreover, in order to increase exposure to the Arab public throughout the world, all references to Israeli military achievements were translated into Arabic and posted on various networks. In addition, there were collaborations with Arabic-speaking influencers from the Gulf states, which echoed the Israeli message, with or without the logo of the IDF spokesman. One example was how material was shared with the Arab press, including the Emirates al-Ain news website, which is known for its hostility to the Muslim Brotherhood, the parent movement of Hamas, and which quoted statements from Adraee.[19]

Exposure to the various channels of the IDF spokesman amounted to some 360 million views, and over half a million new followers were added during the operation. Note that the nature of the spokesman’s activity in the latest round of fighting was no different than previously. As in the past, the IDF made use of social media: its YouTube account was first opened during Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009), while the use of Twitter was first recorded during Operation Pillar of Defense (2012).[20] The innovation in Guardian of the Walls was the first use of the TikTok platform.[21]

Reference to some of the events in Israel during the operation reached social media in Arabic through users who took them out of their original context in ways that helped to incite feelings against Israel. For example, the video showing a burning tree above the al-Aqsa Mosque while Jewish crowds danced and celebrated at the Western Wall below the Temple Mount was presented incorrectly to the Arab audience as a fire caused by Israel (figure 6). Another example was the incident in Jaffa where an Arab boy was injured by a Molotov cocktail. At first the attack was blamed on Jewish rioters, but it later became clear that the bomb was thrown by Arabs. Nevertheless, the report was not corrected by Arab users on social media, who continued to disseminate the photograph of the injured Arab child while attributing the attack to Jews.

Ayman Odeh: Shocking.

Figure 6. The burning tree above the Western Wall

Referring to the conflict between Israel and the Arab world, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah gave a speech on July 5, 2021, after the firing ceased and the military operation was over. He said that the Israelis did not trust their leaders or their media. He also said that everyone knows that “the Palestinians won the campaign, but the news channels and the Israeli media broadcast false information in order to raise morale.” He added that the Hamas media channels did not broadcast lies or delusions, and if they did so, that was part of their psychological warfare against the Zionist enemy.[22] He claimed that the “social media helped to achieve victory for the resistance,” and “while Israel can block satellite channels, it cannot block social media.”[23]

During the operation, there was a digital attack on Israel by an organization calling itself the Malaysian Trolls Army,[24] which operated from Malaysia in a framework called Military Guerilla Activity for Palestine.[25] The campaign included attacks on Israeli social media influencers and IDF officers aimed at closing down their accounts. The Malaysian activity can be divided into two types: disinformation and use of technological means.[26]

The first layer consists of violent hate speech on social media, including the use of hashtags to influence public opinion. One of the Malaysian attacks that used technological capabilities was carried out by a group of Malaysian hackers called DragonForce, who obtained and published the telephone numbers of Israeli civilians and soldiers in order to harass them and block them on WhatsApp by reporting them for improper conduct, or a serial and mass attempt to enter the accounts with the wrong passwords. Tweets were published with an example of trolling against Israelis on WhatsApp.[27] In this framework, personal information of opinion leaders and politicians were revealed in order to encourage others to harass them. For example, personal information about people working in the office of then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was disseminated on Telegram and Twitter.[28] In addition, the cellphone number of Avichay Adraee was published by the Malaysians who claimed that within three hours they managed to block his account (and indeed the claim that his account was blocked for a few days during the campaign has been verified).

As part of a study published by the Information Center for Intelligence & Terror at the Intelligence Heritage Center, groups with about 300,000 participants were found on Telegram channels who were offering training on how to block the profiles of Israeli influencers on the various platforms, to stop them from sharing pro-Israeli posts with international audiences. There was also an explanation of how to harass influencers by making use of their accounts look like inauthentic activity – e.g., Israeli Hollywood stars, such as Gal Gadot, Hanania Naftali, who was a campaigner for the Prime Minister, and dozens of others.[29]

Fourth Arena: International Public Opinion

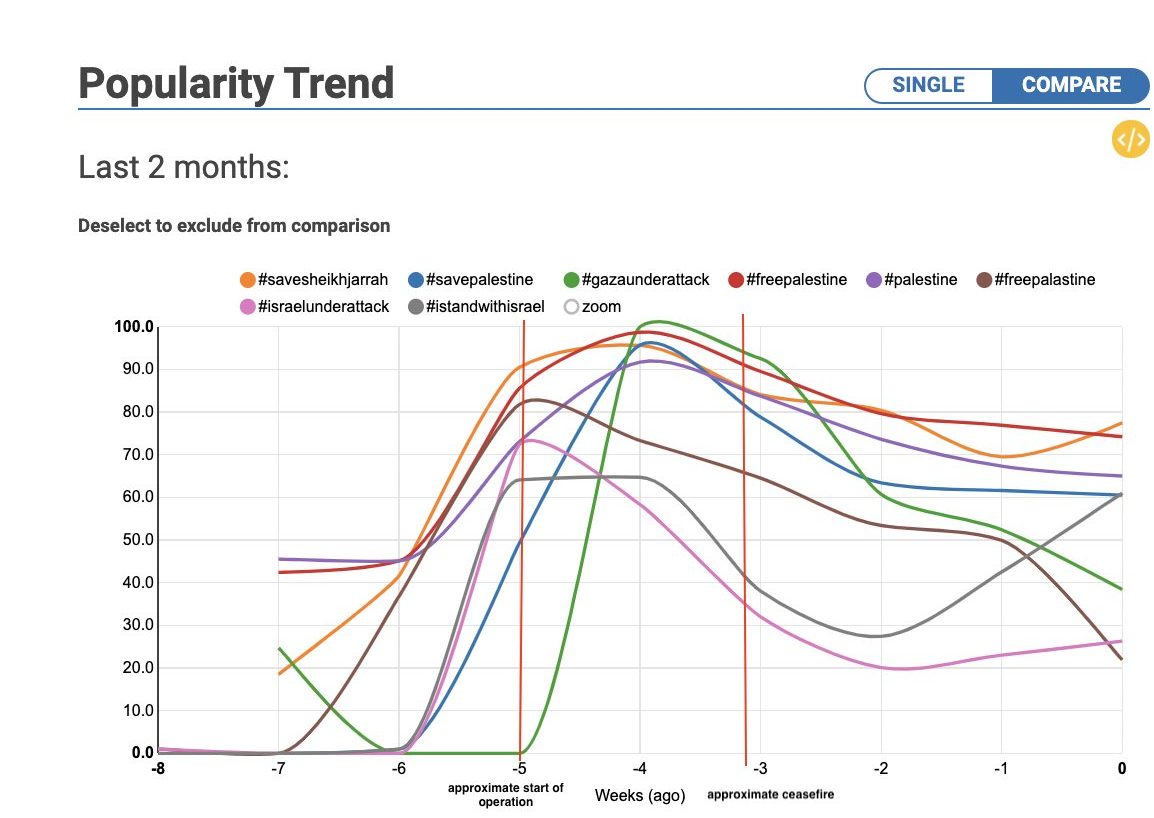

As the kinetic warfare between the IDF and Hamas continued, the battle for global public support of Israel and Hamas reached unprecedented levels online and offline, and found expression in demonstrations and antisemitic incidents. After the ceasefire, when fighting on other fronts ended, the struggle for public opinion on social media continued for several weeks (figure 7). Indeed, hashtags that grew exponentially during the operation retained more popularity on Twitter after the ceasefire than before the operation.

Figure 7. Popularity of Twitter hashtags[30]

The activity on social media directed at the international audience was intended to make them accept the narratives of the various parties by sharing real or false information. At the start of the escalation there was a campaign on social media platforms worldwide, which linked the hostilities between Israel and Hamas to the eviction of Palestinian families from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, and the clashes between Palestinian and Israeli security forces on the Temple Mount. The most important activists on global social media from the Palestinian side included writers, artists, brand name representatives, and independent journalists. For example, Mohammed el-Kurd (649,000 followers on Instagram, 196,000 followers on Twitter) and his sister Muna el-Kurd (1.4 million followers on Instagram), Palestinian twins who were facing eviction in Sheikh Jarrah, became leading voices (figure 8). Indeed, hashtags such as #savesheikhjarrah and #freesheikhjarrah which first started to trend in March, grew exponentially during the operation.[31]

Figure 8. Support for the Palestinian side from global influencers

The main target for the pro-Palestinian campaign is the progressive English-speaking public. The attempt to persuade this target audience is based on positioning the Palestinian narrative in the framework of progressive Western social justice. The terminology and the ideas are selected carefully in order to identify the Palestinian struggle with other popular and thriving movements, such as Black Lives Matter, and to connect it to the aim of ending global violence, oppression, colonialism, apartheid, and white supremacy (figure 9).[32]

Figure 9. Tendentious support for the Palestinian side on social media

The global public was also exposed to pro-Israel content on social media platforms. The IDF English-language spokesman was active on the official Israel Defense Forces Twitter account, which was aimed at the general international public. Tweets on this account during the operation were designed to give legitimacy to military action against Hamas by means of videos and pictures, accompanied by explanations describing how Hamas uses civilian buildings, hospitals, mosques, and schools in Gaza Strip for military attacks on Israel. Many messages from the IDF spokesman showed Hamas attacks on the Israeli civilian front in order to stress the damage and destruction caused by the terror organization (figure 10). Video clips showed civilians in Tel Aviv running to shelters when the alarm sounded, and parents protecting their children from missile strikes.

Figure 10. Sample post from IDF spokesman

Data from the IDF Spokesperson’s Unit show that in the campaign on social media, Hamas had the upper hand in terms of engagement. Every hour some 2,000 pro-Israel tweets were posted by various accounts/users compared to 50,000 attributed to Hamas and activists in the Gaza Strip using hashtags such as #GazaUnderAttack, #SheikhJarrah, #FreePalestine, and there was a similar trend on other social media.[33]

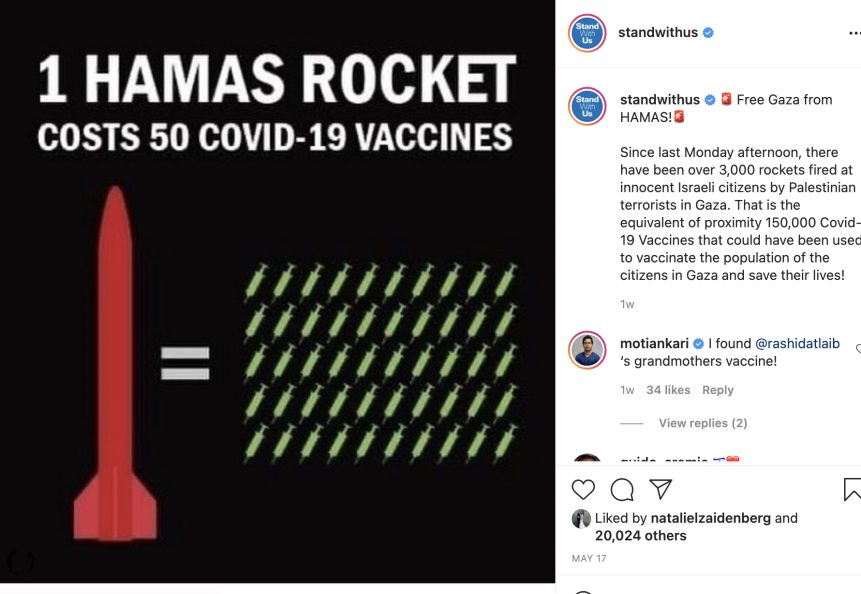

Pro-Israel and Jewish organizations such as AJC Global, StandWithUs, and Act.il took part in the effort to reinforce pro-Israeli messages. Their posts referred to Israel’s obligation as a sovereign nation to defend its citizens and to IDF policy and the effort to minimize damage and injuries to Palestinian citizens, while the goal of Hamas was to maximize the damage to civilians on both sides, making the organization responsible for war crimes and Palestinian suffering.

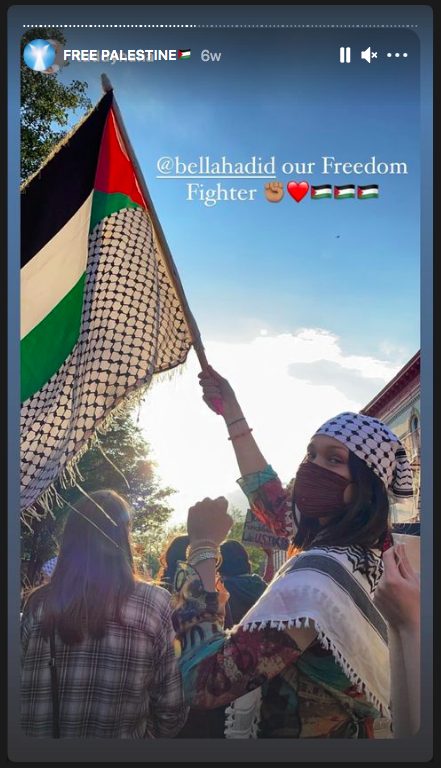

The global discourse on social media was greatly impacted by influencers in various fields. Celebrities who take a stance on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are not a new phenomenon. The most outstanding example during Guardian of the Walls was the model with Palestinian roots Bella Hadid, who used Instagram (43 million followers) to share pro-Palestinian infographics, stories about her Palestinian heritage, and pictures expressing solidarity with the Palestinians (figure 11).

Figure 11. Story on Bella Hadid’s Instagram account

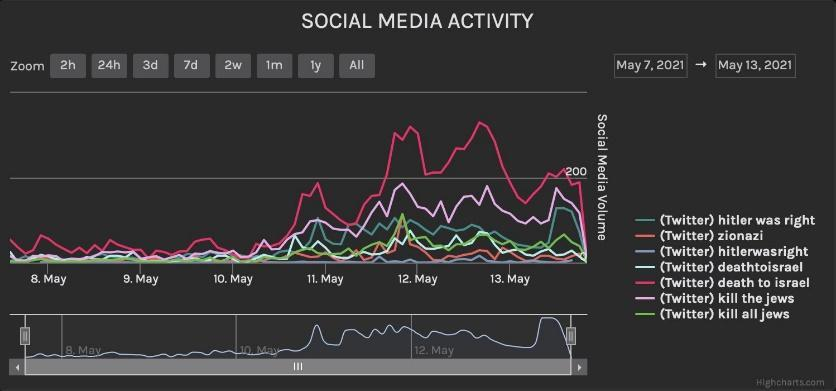

Social media activity during and after Operation Guardian of the Walls also led to a worrying rise in global antisemitism, online and offline. During the operation, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) monitored antisemitic incidents on social media and found, inter alia, an increase in explicit praise for Hitler (figure 12). For example, the hashtag #Hitlerwasright appeared over 17,000 times on Twitter.[34] Well-known Pakistani movie star Veena Malik tweeted a quote from Hitler about killing Jews.[35] The ADL also reported more than 40,000 uses of the hashtag #Covid1948, comparing the birth of the State of Israel to the release of the fatal virus into the world.[36]

Figure 12. Antisemitic Twitter hashtag popularity during Guardian of the Walls[37]

The ADL noted that reports of physical violence against Jews in the United States increased by 75 percent, compared to the two weeks before fighting broke out – continuing the trend of rising antisemitism in the United States over the last four years.[38] The Community Security Trust in the UK reported a 500 percent increase in antisemitic attacks in the United Kingdom during the escalation.[39] While it is difficult to establish a causal link between online incitement and physical violence, many Jewish and Zionist activists blame the demonization of Israel and the Jews online for causing antisemitic violence in real life.

Discussion and Conclusions

Events in the social media digital arena had an impact on public opinion during Operation Guardian of the Walls, and were an integral part of the fighting against Hamas, the violent events within Israel, and the formation of global public opinion. These arenas were active before the operation and continued as such after the ceasefire. It is therefore important to respond quickly to what happens in this arena, taking into account that the rapid pace of technological advances will require constant adaptation of methods.

Reversed Asymmetry Online

Contrary to the real-world asymmetry in which Israel has more military power than non-state organizations with significant military infrastructure and capability such as Hamas (or Hezbollah), the situation is reversed on social media. This reversed asymmetry is expressed at several levels: in narratives, usage tactics, and differences in volume of exposure due to numbers of followers.

At the narrative level, Hamas portrays itself as the underdog, presenting itself to the Arab world and the global arena as a victim. These messages also attract attention among progressive movements overseas, such as Black Lives Matter. Official Israeli channels, by digital accounts of the IDF spokesmen and the Foreign Ministry, promoted content that focused on Hamas attacks on civilians and on official accounts of IDF military actions. Hamas used its official channels to spread false messages; during the operation, official Israeli channels also spread false messages. Israel and Hamas likewise differ in their tactics and approaches. For example, Israel brought down the Hamas website, while the Malaysian Trolls Army acted to block the accounts of Israeli influencers on social media.

One of the most important factors contributing to Hamas achievements in the digital arena is the enormous exposure of accounts that promote messages supporting the organization compared to pro-Israel accounts. The gap is partly due to the languages used – English and Arabic (which have far larger audiences than Hebrew). Ultimately, posts with the hashtag #gazaunderattack, for example, reached far more users than posts with the hashtag #israelunderattack.

New Platforms in Guardian of the Walls: Use of TikTok and Telegram

As technology advances, the social media platforms used by the relevant parties in operations such as Guardian of the Walls also change. In general all social media platforms are used to spread messages among the general public, although each of them has different features and target audiences. For example, instant messaging platforms that are based on direct communication between individual users and the use of groups, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, present different challenges from platforms on which posts are public, such as Twitter pages or Facebook groups.

Inter-Platform Flow of Content; Blurred Lines between Official and Unofficial Channels

One of the main features of activity on social media is the way content flows between different platforms that are aimed at different audiences, and the interface of messages that originate from official and unofficial entities. For example, social media are full of content in English and Arabic, which both reach large numbers of users worldwide. These messages influence global public opinion and how Israel and Hamas are perceived in the world, and they also reach the traditional media.

During Guardian of the Walls unofficial accounts and entities, such as celebrities with large audience of followers, could have far greater exposure than official accounts such as the IDF Spokesperson's Unit. Blurring the divide between official and unofficial channels often means that messages containing errors or that have no factual basis are more viral online.

Disinformation to Deceive and Sow Public Fear

All parties, including organizations, individuals and social media involved in social media during the campaign, on both sides, took part in the deliberate spread of disinformation and unintentional spread of misinformation. One of the most prominent tactics for creating and spreading disinformation during the operation was to show pictures and video clips taken out of their original context. This is an easy way of creating fake news, and in many cases it is relatively easy to identify. Therefore, the way to prevent it is by improving the digital literacy skills of the public and of journalists, who sometimes spread such content.

One of the main challenges presented by the digital arena on social media is the difficulty of knowing who is behind many of the events, the content that is disseminated, and the influence campaigns that appear to emerge from organized systems. For example, at the moment it is not known who was responsible for spreading the WhatsApp messages that helped to create panic among the public, or the series of “desperate Israeli” Twitter accounts that were widely shared by Arab influencers.

No Responsible Authority against Threats to National Security on Social Media

Social media provided the infrastructure for groups to organize and commit violent attacks on Israeli citizens in mixed-population cities during the operation. The police, and particularly the GSS, began to block social media accounts, but these measures proved too little, too late. These events illustrate the absence of a responsible authority to examine incidents in these digital arenas – from outside and from inside – with the focus on efforts to protect against threats deriving from the cognitive warfare in the digital arena, and how the discourse spreads on social media. Without constant monitoring and enforcement, together with the development of intelligence gathering capabilities, there will be no deterrence against a breach that could endanger national security in a number of ways and contexts – even after Guardian of the Walls and similar events. This is due to the large numbers of groups on the ground created in recent years on apps such as WhatsApp and Telegram.

At present there is no authority in Israel with the responsibility for monitoring and handling external and internal threats to national security that originate in the arenas discussed in this article, taking a broad view of how they influence each other. In other words, the issue of responsibility for what happens on social media remains open. The vacuum is sometimes filled by civil society organizations; some are mentioned here. Of course, there is tension between the need for this role on a national level and the need to maintain freedom of speech and personal privacy, but events in the digital arena of social media during Guardian of the Walls show – again – that the issue must be addressed, nationally, within civil society, and by social media giants.

Each arena may be monitored by different enforcement authorities, but there are common principles that apply to all. For example, it must be possible to act swiftly with social media companies in order to remove incitement or false content that is dangerous to national security and citizens. This means strengthening the procedures for emergency action to secure the immediate removal of violent and incendiary content, and to respond to hostile foreign intervention. It also includes promoting steps to improve digital literacy among the public who share messages and posts, and stressing the obligation of the traditional media to verify information before publication.

Systemic Ability to Look at Defense and Offense Together

At a national level there is a need for the ability to connect defense and offense on social media, efforts to influence public opinion, and efforts to prevent the enemy’s activities, or at least minimize their impact. This combined approach must integrate with Israel’s other efforts to influence public opinion using political and military means.

Operation Guardian of the Walls highlights the lack of national public diplomacy, with the emphasis on the digital arena, to direct and synchronize the activity of all organizations seeking to influence cognition, and to recruit the public in Israel and worldwide for pro-Israel public diplomacy campaigns. Social media enable the general public to participate in such campaigns, and the country must establish a reliable knowledge base that pro-Israel entities in Israel and throughout the world can use in their efforts to exert influence on social media and traditional media.

The Role of the Public

Due to the open nature of the internet and social media platforms, ordinary citizens and hostile foreign influences operate concomitantly and in the same space. Sometimes, the public may unknowingly help to spread hostile or false messages from outside sources that are likely to increase public anxiety, particularly in times of war when tensions are already high.

In many cases, it is not possible to know if there is an authority such as a state or a state-owned organization that drives the public in message dissemination. In other words, is the sharing of certain content, such as posts designed to influence how Hamas is perceived by the global public, an authentic expression of attitudes on the ground, or has it been planted by professionals working for the organization? The authentic appearance of social media posts with content that arouses strong feelings makes the general public more inclined to pass them on to others, whereas posts from official sources of information are more likely to be received with suspicion by the public. It is therefore important to improve digital literacy skills through education so that people will be more aware of the content they are sharing, able to identify fake news more easily, and slow down the spread of false rumors. This subject should be coordinated at the national level.

No comments:

Post a Comment