MICHAEL PECK

During the Cold War, Russia became the first nation to launch a satellite, and then a human being, into outer space. With more than 160 Russian satellites in orbit today, every Ukrainian city, tank, and howitzer should be exposed to the unrelenting gaze of orbital cameras.

But that’s not happening on the battlefield. While Ukraine’s military is reaping enormous benefits from commercial communications and photographic satellites, Russia is only getting meager rewards from its huge investment in military spacecraft, according to a Western expert.

“The Ukrainian army can use commercial systems to obtain images of any area in high detail at least twice a day in favorable weather conditions, whereas the Russian army can get an image of the same area approximately once in two weeks,” Pavel Luzin, a senior fellow at the Jamestown Foundation, wrote in a recent article for Riddle. In addition, “existing Russian satellites provide seriously inferior quality of imagery vis-à-vis American and European commercial satellites.”

GPS satellites have enabled Ukraine’s American-made HIMARS guided rockets to accurately target Russian supply depots and headquarters. SpaceX’s Starlink—which uses numerous low earth orbit satellites to provide connectivity through backpack-sized ground stations—became indispensable for Ukrainian military communications.

Yet despite a huge array of hypersonic and other guided missiles and smart bombs, Russia has not been able to conduct precision strikes. “Because of a lack of reconnaissance capability, Russia is not able to use its high-precision weapons in the planned way,” Luzin told Popular Mechanics. “That’s why Russia started its campaign of missile terror against the cities and civil population of Ukraine.”

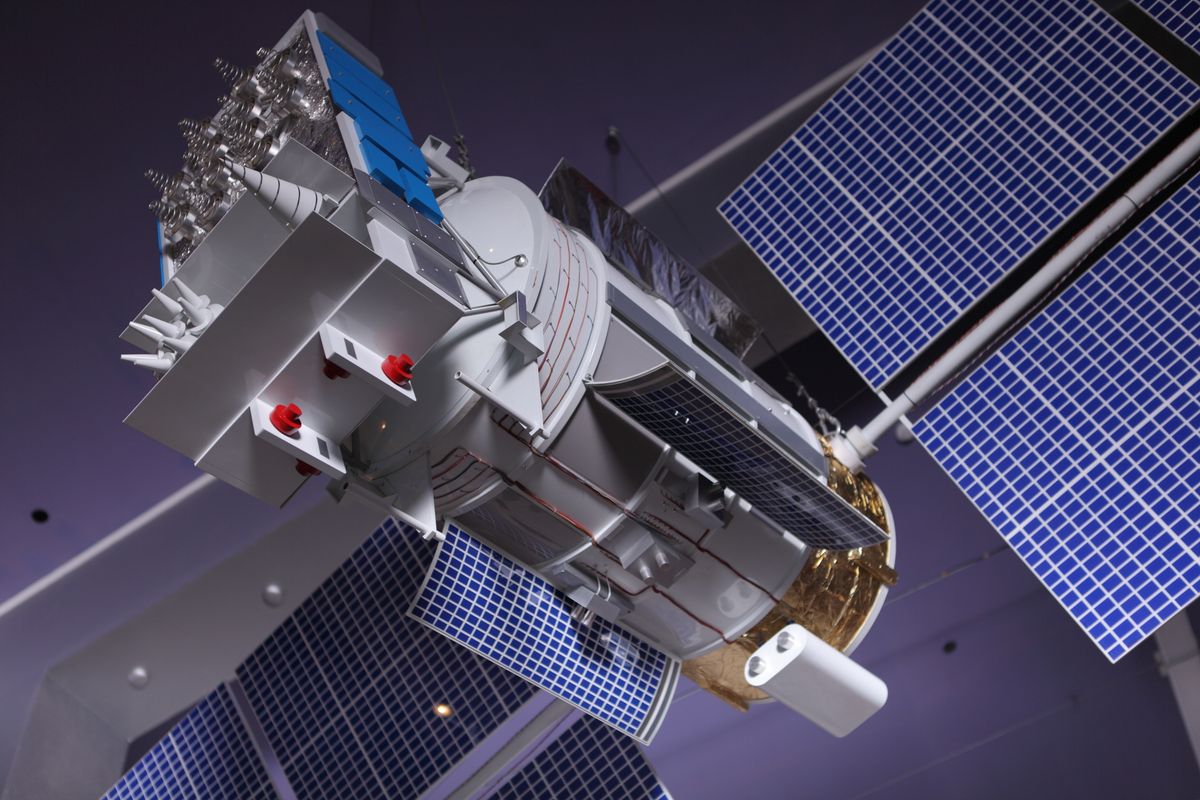

The problem isn’t a lack of orbital hardware. Russia has more than 160 satellites in orbit, of which more than 100 are military systems, according to Luzin. These include 25 GLONASS GPS satellites, 47 communications satellites, seven Liana oceanic electronic reconnaissance satellites, two Persona optical reconnaissance satellites, as well as assorted missile detection, topographic mapping, and experimental spacecraft.

What Russia does lack is the right mix of satellites, as well as the ground systems and procedures to receive and disseminate data to those who need it. For example, the Liana spacecraft are designed to track ships. But Russia has always been a land rather than a naval power, and being able to track U.S. aircraft carriers in the Pacific doesn’t help win a ground war in Ukraine.

Realizing that it was falling behind in the new Space Race, Russia opted in the early 2000s not to build spy satellites. “The Kremlin decided to start with the satellite navigation system GLONASS and communication satellites that rely on Western space electronic components,” Luzin said. “The reconnaissance satellites were the much harder task for the Russian space industry, and it turned to this task just in the early 2010s.”

But the imposition of Western sanctions after the 2014 annexation of Crimea hampered investment in reconnaissance systems. The result is that Russia has just two optical intelligence (photographic) satellites in orbit now. Two new Resurs satellites have been delayed until at least 2024, while three Russian commercial satellites—which could be used for military imagery—may no longer be functional.

While the exact number of U.S. spy satellites is classified, the National Reconnaissance Office planned at least seven launches in 2022. The agency is now contracting with commercial companies for hyperspectral satellite imagery that can detect objects through multiple bands of light.

It isn’t just satellites that are the problem. Troops lack satellite communications terminals, which only exacerbates the Russian military’s rigid and compartmentalized command system. While the GLONASS GPS satellites work, users lack terminals and electronic maps to utilize satellite navigation.

In 2020, Luzin estimated that Russia was spending $1.6 billion per year on its military space program. Yet funding for future Russian satellites is uncertain. The Ukraine war will divert resources to tanks and missiles. Meanwhile, Western sanctions will deprive Russian spacecraft of sophisticated components.

Nor is turning to commercial satellites—as Ukraine successfully did—an option. “Russia’s political economy model makes private efforts in outer space just impossible,” Luzin said. “Private business and technology initiatives are considered political threats.”

The West can also take steps to prevent the revival of Russia’s military space program. “It is necessary to prevent Russia’s access not only to space-grade electronics, but also advanced industrial equipment,” said Luzin. “Also to commercial satellite services using rogue firms in Asia and Europe.”

As one of the two original spacefaring nations, it is not realistic to assume that Russian satellites will disappear from the heavens. But the glory days of Sputnik and Soyuz seem to be gone.

“I don’t think Russia is capable of developing its military space capabilities now,” Luzin said.

No comments:

Post a Comment