Emily Rauhala, Kareem Fahim and Michael Birnbaum

VILNIUS, Lithuania — Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Monday agreed to support Sweden’s NATO bid, a high-stakes, last-minute reversal that came after a year of obstruction and on the eve of a major alliance summit.

The deal, announced Monday in the Lithuanian capital, does not confer membership. But if Turkey and fellow holdout Hungary indeed ratify Swedish accession, NATO will grow, cementing a major shift in European security in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“This is a historic day,” said NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, expressing confidence that Erdogan would move quickly to have the Turkish legislature approve the ratification. Hungary has said it does not want to be last to ratify, and Stoltenberg said “that problem will be solved.”

President Biden welcomed the news, saying he looks forward to welcoming Sweden “as our 32nd NATO ally.”

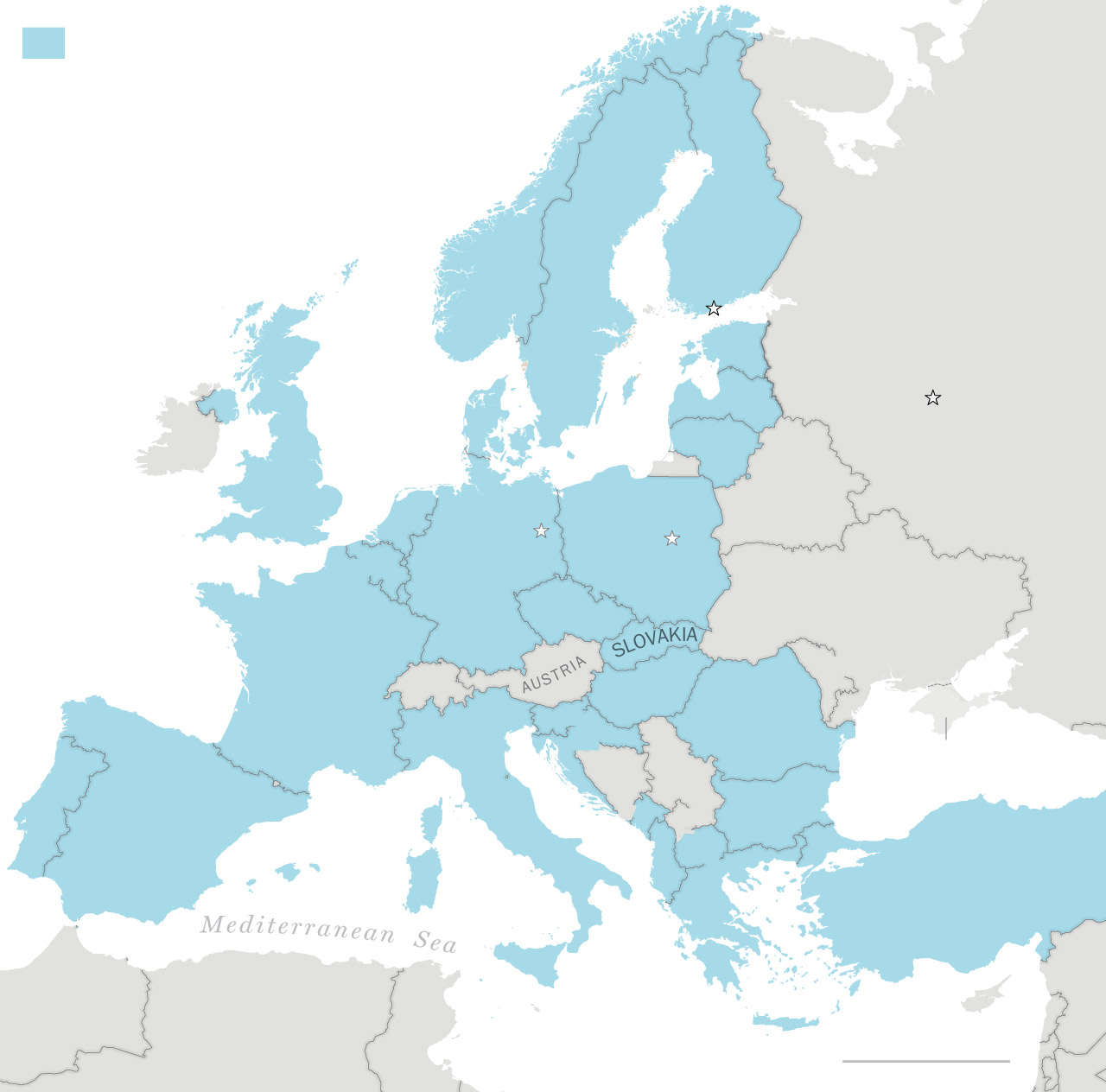

Sweden has a robust military, and its entrance would drop the final puzzle piece into the alliance’s Nordic region, fully ringing the Baltic Sea with NATO coastline — apart from the parts that are Russian territory. Military planners say NATO’s defenses will be significantly stronger as a result.

The deal is also good news for an alliance that has struggled with how to handle Erdogan’s demands, particularly as war rages in Ukraine.

While Monday’s announcement was a surprise, it followed something of a pattern established by the Turkish leader, who has held out on major decisions related to the alliance, only to relent once leaders have begun gathering. This strategy has helped him dominate headlines — and also to extract concessions.

On the eve of last summer’s NATO summit, Erdogan agreed, in theory, on a membership path for Finland and Sweden — though he later said that Sweden wasn’t upholding its side of the bargain.

In exchange for giving a green light to Sweden this time, Erdogan got Stockholm to agree to continue counterterrorism cooperation with Ankara. Sweden also said it would push inside the European Union to reduce trade barriers with Turkey and to make it easier for Turkish citizens to enter the E.U. Stoltenberg agreed to appoint a NATO counterterrorism coordinator, long a request of Turkey’s.

The joint news release said Sweden “reiterates” it would not support groups Turkey regards as terrorist entities — a key Erdogan demand — including a movement accused of trying to overthrow Erdogan’s government in 2016 and a Kurdish militia in Syria affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which has fought a long insurgency against the Turkish government.

Turkey’s main focus, analysts said, has been the completion of a $20 billion deal for American F-16 fighter jets, an agreement that is backed by the Biden administration but has faced opposition on Capitol Hill.

The planes were not mentioned by Stoltenberg nor by the Turkish and Swedish leaders in their joint declaration, and it was not immediately clear whether there had been a side deal with the United States. Some senators, including Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), have vowed to block the sale of the jets until Sweden is admitted to NATO.

Biden and Erdogan were scheduled to meet Tuesday.

When the two leaders spoke by phone Sunday, Erdogan still appeared to be adding to his long list of reasons Sweden shouldn’t be allowed to join NATO. In the call, according to the Turkish government’s summary, and again speaking to reporters Monday, he appeared to link Sweden’s bid to Turkey’s long and fruitless effort to join the E.U.

“The blackmail is endless,” said a senior NATO diplomat, speaking on the condition of anonymity to criticize an ally.

After the deal was announced, the diplomat expressed satisfaction. “Europeans pushed back vigorously,” the diplomat said, but accession could still snag should Erdogan decide to wriggle out of the agreement.

Erdogan’s demands — and his dramatic announcement — ensured that Turkey remained at the center of the conversation as Western allies met to discuss other critical issues related to Russia’s invasion. All the headlines bolstered Erdogan’s efforts to promote his government as an independent, if unpredictable, power broker with global reach.

“Erdogan likes to throw people off balance,” said Asli Aydintasbas, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Finland and Sweden abandoned years of military nonalignment to seek security in NATO — only to face pushback from Turkey. Joining NATO requires unanimous approval from member countries.

A year ago, at the NATO meeting in Madrid, Erdogan dropped his opposition to Finnish and Swedish membership at the summit, stealing the show and raising hope for a quick accession process.

But the deal soured quickly, with Turkey continuing to call out Sweden for its refusal to hand over Kurds accused of being militants, and Hungary, an ally of Ankara, also signaling opposition. Ultimately, Finland decided to move ahead without Sweden, joining the alliance in April after Turkey approved its membership.

Along with citing Sweden’s reluctance to extradite people Ankara sees as terrorists, Turkey also complained about anti-Erdogan protests held in Sweden and Quran-burning demonstrations.

Those complaints dovetailed with populist rhetoric Erdogan used at home, including during the presidential election in May, when he portrayed his opponents as sympathetic to Kurdish militants and as enemies of traditional Muslim family values.

Sinan Ülgen, a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe in Brussels, said that while there was a “domestic angle” to Turkey’s posture on Sweden, which Erdogan used to earn political support, his opposition was “never just an election tool.” Rather, Ülgen said, it was a bargaining chip to extract concessions from the United States.

Provocative remarks from Erdogan in the run-up to this year’s summit left officials and analysts wondering whether Sweden’s bid was doomed or if Erdogan was simply flexing his muscles.

“This is his negotiating style,” Aydintasbas said in a text message. “He knows Turkey will not get into the EU. But he wants Europeans to also put something on the table — and match U.S. efforts to free up F-16 sales to Turkey,” she said.

His comments on E.U. membership — conjuring a decades-long, frustrating process for Turkey, for which European governments shouldered some of the blame — was also a dig at the West. “He is making fun of NATO’s high talk of values and bringing it down to simple give and take,” she said.

The E.U. dismissed the idea of tying Sweden’s NATO bid to E.U. enlargement: “You cannot link the two processes,” Dana Spinant, a spokesperson for the European Commission, said Monday.

A spokesperson for the National Security Council said the United States had “always supported” Turkey’s E.U. aspirations “and continues to do so,” speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss diplomatic negotiations. While Turkey’s “membership and process” was between the E.U. and Turkey, they added, the U.S. focus was “on Sweden, which is ready to join the NATO alliance.”

Anna Wieslander, director for Northern Europe at the Atlantic Council, last week predicted Erdogan’s turnaround. “It’s possible that Erdogan could be staging this so he could be the good guy,” she said, “Saving the summit by giving a unilateral green light.”

Fahim reported from Istanbul. Beatriz Ríos in Brussels, Kate Brady in Berlin and Toluse Olorunnipa in London contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment