By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

Compare that to Patriot missiles, which require special launchers and cost roughly $3 million each. The Hypervelocity Gun Weapon System (which comprises the HVP itself plus cannon, fire control, and radar) won’t replace high-cost, high-performance missiles, but it could provide an additional layer of defense that’s cheaper, more mobile, and much harder for an enemy to destroy.

Today’s missile defenses are “brittle,” “inflexible,” and “expensive,” said Vincent Sabio, the HVP program manager at the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office. “We need to be able to re-engineer (missile defense) from the bottom up (and) go back to Congress and say, ‘We have a choice here: We can either have an effective defense, or we can continue inching along the way we are with our heads in the sand.'”

The most basic problem is a simple, if daunting one: we can’t afford many interceptors. In addition, current systems require bulky launch systems an enemy can easily detect: a trailer for Patriot, a truck for THAAD, a silo for GBI. “As a result, the adversary is able to count interceptors; they know where our sites are; and they can simply play what we call the plus-one game,” Sabio said at CSIS. “They know if you have x number of interceptors, the absolute most they need to throw at you is x threats. And once you have fired your x interceptors, they pretty much own you.”

Note that Sabio’s presenting the best possible case: Since real-world reliability rates and “shot doctrine” require firing two interceptors at each incoming threat, an adversary can probably run us out of ammo by firing half as many offensive weapons as we have interceptors. What’s more, a typical offensive missiles — which just has to hit the right coordinates on the ground — is much cheaper than a defensive missile — which has to hit a rapidly moving target.

Today’s missile defense interceptors are ultra-high-performance systems, Sabio said, designed to take out an incoming threat in a single shot with a high Probability of Kill (Pk). (Whether they live up to that specification in practice is a matter of much debate and testing). But there’s another way to get a high Probability of Kill, Sabio says: Fire lots of cheap weapons, each with a low Pk on its own, but a high probability that one will hit eventually.

(Sabio didn’t offer numbers, but to give an extreme case, even a weapon with a 10 percent Probability of Kill per shot — i.e. it misses 90 percent of the time — has a 90 percent chance of killing the target if you fire it 22 time). That’s where the Hyper Velocity Projectile comes in.

BAE Hyper Velocity Projectile (HVP)

“That projectile has been independently costed — not by me, I wouldn’t expect to you believe my costing — but … by NavyIWS at about $85,000 a round,” Sabio said. “You can shoot a lot of those things and not feel badly about it.” In rough terms, for the $3 million price of one late-model Patriot, you could buy about 35 HPVs.

Admittedly, $85,000 is more than triple the early estimates for a single HVP round. But the original $25,000 figure was probably for the surface-to-surface version, intended to hit ships and ground targets, which didn’t require the same sensors and maneuverability as an HVP would to catch a high-speed missile. In fact, Sabio wants his weapon to be able to adjust how it operates to catch different kinds of missile — something current interceptors don’t do well.

Flexibility

“That projectile is being designed to engage multiple threats,” Sabio said of the HVP. “There may be different modes that it operates in (in terms of) how does it maneuver, how does it close on the threat, and whether it engages a (explosive) warhead or whether it goes into a hit-to-hill mode. Those will all be based on the threat, and we can tell it as it’s en route to the threat, ‘here’s what you’re going after, this is the mode you’re going to engage in.'”

Test of a Navy Trident D5 submarine-launched ballistic missile.

Versatility is a priority for the Strategic Capabilities Office. Created by the last administration, SCO has helped turn the Navy’s SM-6 anti-aircraft missile into a ballistic missile defense interceptor and even ship-killer, for example. It’s trying to turn the Army’s ATACMS artillery missile into an anti-ship weapon too. But most missile defenses today are optimized to kill ballistic missiles ranging from Scuds to ICBMs, not cruise missiles, drones or hypersonic weapons.

“We need to be able to address (all) types of threats: subsonic, supersonic; sea-skimming, land-hugging; coming in from above and dropping down on top of us,” said Sabio. “There are many different trajectories that we need to be able to deal with that we … cannot deal with effectively today.”

A ballistic missile is the fastest way to get a warhead from A to B, but it’s also a pretty predictable target.After its rocket motors have finished burning — the heat can be detected from space — it follows a smooth ballistic curve (hence the name). If you’re worried about ballistic missile threats from a particular country, like North Korea, there are only so many possible trajectories it can take. By contrast, cruise missiles and drones are harder to detect and predict because they fly like aircraft.

“Our adversaries are …. developing weapons that can come in and engage on multiple axes,” said Sabio. “We cannot allow our adversaries to simply fly around our sensor systems and come in and attack us on an axis where we’re blind.”

But getting 360-degree coverage is “prohibitively expensive” with current fire control radars, Sabio said. HVP’s using an off-the-shelf Marine Corps G/ATOR radar for long-range surveillance, he said. When the G/ATOR picks up a target, it passes the data to a radar interferometer for fire control. Each interferometer covers a 90 degree arc from ground level to zenith, so four of them together cover all directions.

The first interferometer, now being built, costs $23 million, Sabio said. Assuming that price doesn’t come down — as usually happens after the first unit produced — that means $92 million to have 360-degree fire control for a battery of guns.

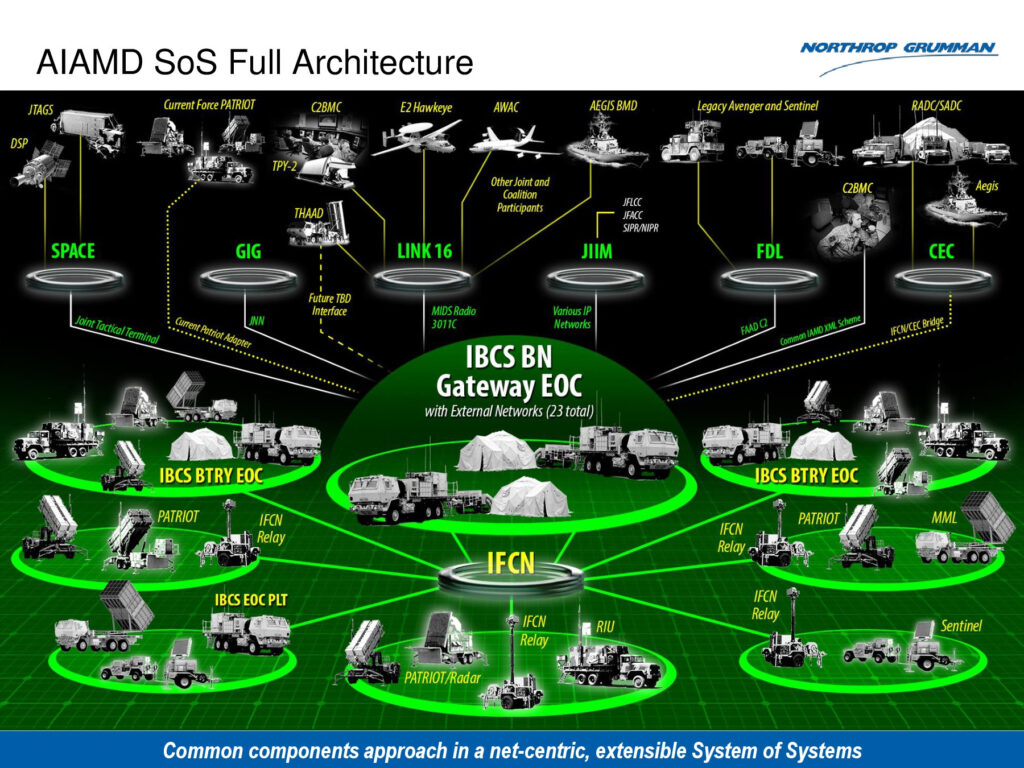

A simplified (yes, really) overview of the IBCS command-and-control network for air and missile defense.

Many Shooters

The final expense is trickier to calculate: the cost of the launchers. Patriot launchers can only fire Patriots interceptors; THAAD launchers can only fire THAADs, “but those (HVP) projectiles…are shot out of Army 155 (mm) howitzers and they’re shot out of Navy five-inch deck guns,” Sabio said. The military has hundreds of those, already paid for.

There will be some additional cost. While the Navy deck gun can fire HVP without modifications, Sabio said, the Army howitzer must be upgraded with a longer barrel, better muzzle brake, and other improvements. This kit, called Extended Range Cannon Artillery, was already being developed to fire conventional shells further. Its cost is not yet clear.

Using howitzers and deck guns also gives HVP a major tactical advantage. “Any place that you can take a 155 (howitzer), any place that you can take your navy DDG (destroyer), you have got an inexpensive, flexible air and missile defense capability,” Sabio said. The impact on the Navy is significant. Destroyers can already carry missile defense interceptors, but only limited numbers, so the HVP would give them many more shots. The impact on the Army is dramatic: Howitzers — both towed M777s and M198s and self-propelled M109s — are much more mobile and vastly more numerous than Patriot or THAAD launchers.

Army prototype Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA) with elongated barrel

The more missile defense units you have, and the more mobile they are, the more you can disperse them to cover multiple angles of attack on many potential targets. Dispersion also makes it much harder for the enemy to find your missile defenses and wipe them out. The enemy’s problem gets even harder if those missile defenses can also take out his launchers preemptively, as guns firing HVP could do. (Remember, the Hyper Velocity Projectile is also capable of hitting static targets).

So when will the Army and Navy actually get Hyper Velocity Projectiles? Both services are already working with SCO to plan a handover of the program, Sabio said. His role is just to prove the key technology works: specifically, to demonstrate that an HVP can maneuver close enough to “an inbound, maneuvering threat” that it could have destroyed it if fitted with the proper warhead. Sabio’s not developing that warhead.

“We are building out the full fire control loop including the sensors, the coms links, the projectile, the launchers (i.e.) the guns,” he said. “The command and control…. I leave that to my independent transition partners, Navy and Army.”

And by when will the demonstration happen? “Well,” said Sabio, “my program ends less than a year from now.”

No comments:

Post a Comment