As China has built its naval power, it has relied on a variety of ideas—old and new, Eastern and Western. For U.S. military leaders seeking to understand China’s naval aspirations, certain images can bring the strategy into focus—like the crumple zones built into a modern automobile, designed to give but not fail. Exploring the context in which China is amassing sea power will help U.S. military leaders comprehend its maritime strategy, along with the forces and methods China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLA Navy) and affiliated joint forces are deploying to fulfill their operational and strategic goals. Great figures from the past can guide the investigation—illuminating different aspects of Chinese strategy, operations, and tactics.

As China has built its naval power, it has relied on a variety of ideas—old and new, Eastern and Western. For U.S. military leaders seeking to understand China’s naval aspirations, certain images can bring the strategy into focus—like the crumple zones built into a modern automobile, designed to give but not fail. Exploring the context in which China is amassing sea power will help U.S. military leaders comprehend its maritime strategy, along with the forces and methods China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLA Navy) and affiliated joint forces are deploying to fulfill their operational and strategic goals. Great figures from the past can guide the investigation—illuminating different aspects of Chinese strategy, operations, and tactics.

Chinese Sea Power: More Than the PLA Navy

Sea power is no longer a matter for fleets alone. It is no longer even an exclusive province for navies. Air forces, armies, and strategic rocket forces increasingly can reach out to sea, acting as terrestrial implements of sea power. Naval constitutes a subset of maritime , in short, and there are many tools of maritime might. They are all subservient to China’s larger military strategy, and thence to the political purposes China’s armed forces serve.

It was not always thus. Once upon a time fleets met in action far from shore, dueling for command of the sea and the fruits it brings. They pummeled each other out of reach of shore artillery, whose range was limited to a few short miles. Naval commanders mostly stood off from shore, confining their efforts to the high seas. For instance, Lord Horatio Nelson’s triumph at Trafalgar (1805) took place in waters isolated from land. It was a genuinely naval battle. Yet even during the age of sail, naval commanders glimpsed the potential of coastal gunnery. Nelson, Great Britain’s god of high-seas battles, counseled that a ship is a fool to fight a fort.

Photo: Chinese Navy multi-role frigate Hengshui (572) fires the main gun during a gun exercise at Rim of the Pacific 2016. U.S. Navy photo.

Skirting shore defenses remained smart practice into the age of steam. The Battle of Jutland (1916) was another strictly fleet-on-fleet encounter. Britain’s Grand Fleet brought all its ships and armaments into the North Sea, Germany’s High Seas Fleet brought all its assets, and they had a gunfight.

It is doubtful, however, that the future will witness the likes of Trafalgar and Jutland. With the advent of long-range precision-guided firepower, future encounters will bear more resemblance to the Solomon Islands campaign 75 years ago. During that expedition, U.S. and Japanese ground, air, and sea forces wrangled for six months for control of Henderson Field, an airfield on Guadalcanal. Control of the airstrip would furnish the victor a staging point to raid enemy shipping and island bases throughout much of the South Pacific. Land-based sea power, then, represented both the goal of the Solomon Islands campaign and one of the principal weapons for waging it.

The guided-missile age only hastened the onset of land-based sea power, expanding its reach, precision, and lethality. Chinese strategy is turning this firepower revolution to advantage. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will harness all available implements of maritime might to mount a forward defense of Chinese shores. China’s nautical arsenal features high-profile warships such as aircraft carriers and guided-missile destroyers—ships that make up the battle fleet. The inventory also includes short-range fast-patrol craft and diesel-electric submarines packed with antiship cruise missiles. Missile-toting aircraft play their part, flying from airfields ashore. Truck-launched antiship missiles likewise qualify as instruments of sea power.

The PLA has devised a Maoist “active defense” strategy—rebranded “offshore waters defense” in recent years—that alloys these sea- and land-based elements of sea power into a single sharp weapon to defend Fortress China and offshore waters against the United States and its allies. How will they unlimber that weapon? East Asia and the western Pacific come first for Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders. Strategy is the art of setting priorities while marshalling the gumption to enforce them. It would make little sense to place the primary theater—the homeland and adjoining waters—in jeopardy for the sake of secondary enterprises in faraway seas. Access starts at home for China.

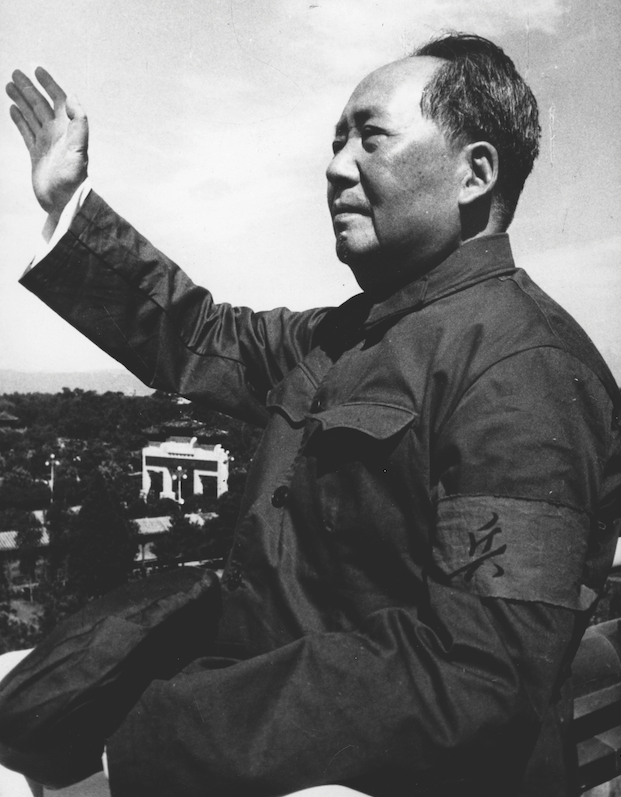

At left: During China’s civil war, Chairman Mao counseled Red Army commanders to “lure [stronger enemy forces] in deep” and annihilate them bit by bit, falling on and crushing isolated units. ALAMY photo.

At left: During China’s civil war, Chairman Mao counseled Red Army commanders to “lure [stronger enemy forces] in deep” and annihilate them bit by bit, falling on and crushing isolated units. ALAMY photo.

But if PLA commanders could defend the homeland and China’s Pacific interests with ground-based weaponry, diesel submarines, and fast-attack craft, the CCP leadership could spare a sizable fraction of the PLA Navy surface fleet for ventures beyond China’s geographic environs. Over time it could evolve into an expeditionary fleet, the bearer of Beijing’s foreign policy in far-flung seas. As political leaders gain confidence in offshore-waters defense, they increasingly will turn their attention and energies to expeditionary pursuits. They can detach naval forces for “open-seas protection” and kindred missions without running undue risk at home.

And indeed, China’s leaders are laying both the intellectual and material groundwork for out-of-area ventures. This is noteworthy. After all, open-seas protection and other expeditionary ventures are missions navies undertake once they command the waters strategists and their political masters care most about. That Beijing feels comfortable inaugurating a turn to the Indian Ocean and other seaways thus speaks volumes about the leadership’s confidence in the capacity of joint naval, air, and missile forces to execute an active defense close to home.

What does this mean for U.S. defense planners and for U.S. allies and partners in the region? It means China feels increasingly self-assured about its dominance of regional waters and skies. And it means the United States and its allies and friends in East Asia must field a strategy backed by the requisite hardware to counter China’s offshore-waters defense strategy. In so doing the United States can ensure access to the allies without whom it has no strategic position in Asia. If we compete effectively in the western Pacific, we can beckon PLA Navy forces homeward to guard China proper—and indirectly ease Chinese pressure in the Indian Ocean and other embattled seas.

To reinforce alliances and to restrain China’s growing extraregional naval presence, the United States should fix its strategic gaze squarely on East Asia—and apply its seaborne energies and resources there.

Goal: An Offshore “Crumple Zone”

There is an everyday metaphor for China’s “antiaccess/area-denial” strategy: Think of it as an effort to construct an offshore “crumple zone” using sea- and shore-based weaponry. The engine compartment of a car’s front end and the trunk to its rear comprise its crumple zones. These are not inflexible shields. They are sacrificial components meant to collapse in a controlled manner upon impact. The chief purpose of automobile design is to protect what car manufacturers prize most—the safety of passengers inhabiting the cabin. If the crumple zone were completely rigid, the force of a crash would be transmitted straight to the cabin and to the people within—and possibly kill them. Instead, the crumple zone absorbs the energy from an impact, cushioning the blow.

Antiaccess logic operates similarly. Security for the mainland and the near seas is what Beijing treasures most. Yet PLA commanders do not delude themselves that they can make the western Pacific a no-go zone. They know they cannot erect a defensive perimeter that blocks the U.S. Pacific Fleet out of regional waters altogether. Military history has been unkind to efforts to defend long, distended frontiers. Not even the Great Wall was an impenetrable edifice; nor did its builders intend it to be. No armed force can make itself stronger than potential foes at every point along a line. Defenders must spread out, thinning their combat power. Dispersal lets even an ostensibly weaker opponent mass locally superior forces at some place along the perimeter and puncture it.

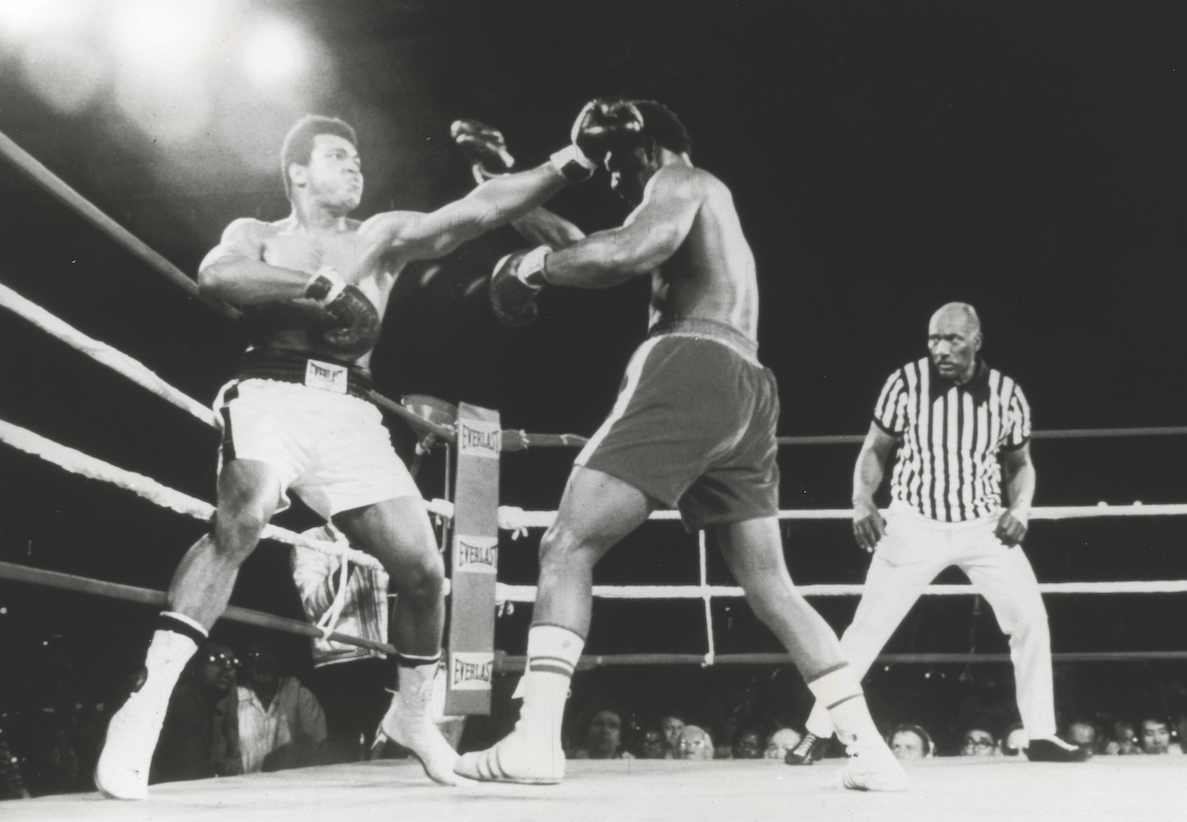

Muhammad Ali's masterful performance in the 1974 "Rumble in the Jungle" against George Foreman is a powerful analogy for China's use of temporary strategic retreat. Photo: Alamy

Clausewitz Goes to Sea

What PLA defenders can strive to do is impose high—if not unbearable—costs on U.S. Pacific Fleet reinforcements surging westward to the relief of Japan or some other ally and on U.S. forces already forward deployed to the region. That is why the first face to put on China’s offshore-waters defense is that of martial sage Carl von Clausewitz. Clausewitz teaches that there are three ways to prevail in wartime. To oversimplify, one can smash, overawe, or bankrupt a foe. Says Clausewitz, it is commonplace for wars to be “fought between states of very unequal strength ”—and it is far from uncommon for the lesser pugilist to come out on top. “Inability to carry on the struggle,” he continues, “can, in practice, be replaced by two other grounds for making peace: the first is the improbability of victory; the second is its unacceptable cost.”

In other words, if China can dishearten its adversaries or drive the price of entry into the Western Pacific so high Washington is unwilling to pay it, then China can win without crushing them in a major fleet engagement. Such an engagement would hold at risk the PLA Navy surface fleet in which Beijing has invested lavishly over the past two decades and that it needs for open-seas protection missions in distant seas. Instead the PLA leadership can dare U.S. political leaders to hazard the Pacific Fleet in action and risk incurring heavy damage that imperils the U.S. Navy’s capacity to uphold U.S. interests, not just in Asia but elsewhere around the Eurasian periphery.

The White House might balk at paying a steep price or risking defeat at sea. If it did, Beijing would gain time—a treasured commodity in times of crisis. Clausewitz would approve of how China deploys military hardware for psychological effect.

Mao Defends Actively

Robust capability thus affords China the ability to deter or coerce. The next face of Chinese sea power is Mao Zedong’s glowering mien. In 2015, by way of its first official military strategy, China’s leadership reminded us that Maoist active defense remains not just relevant to Chinese strategy making: the “strategic concept of active defense is the essence of [CCP] military strategic thought.” 1 (Emphasis added.) What that means is that PLA forces will not try to protect a fixed defensive perimeter, and they will not offer decisive battle far out in the Pacific Ocean. They will stage a fighting retreat—yielding sea space while launching piecemeal attacks to cut the U.S. fleet down to size in preparation for a naval action somewhere within the crumple zone.

This bend-but-don’t-break approach is true to Chinese Communist traditions rooted in ground warfare. Mao delighted in using metaphors to explain himself. During China’s civil war he counseled Red Army commanders to “lure [stronger enemy forces] in deep” and to annihilate an enemy force bit by bit, falling on and crushing isolated units. “Injuring all of a man’s ten fingers,” he maintained, “is not as effective as chopping off one, and routing ten enemy divisions is not as effective as annihilating one of them.” Lop off one finger, then the next, then the next. Mao demanded that the Red Army comport itself like a savvy boxer: think of the great Muhammad Ali in the 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle,” who let his brawnier opponent George Foreman flail away and waste his energy in the early rounds only to expose himself to crushing counterpunches and defeat in the later rounds. Temporary strategic retreat worked for Ali and for Mao’s Red Army. Why not today’s PLA?

What that means in practical terms is that the PLA is amassing weaponry capable of striking at the U.S. Navy hundreds of miles offshore and wearying it as a precursor to a Pacific Trafalgar. Doing so represents a weaker China’s great equalizer. The PLA armory includes antiship missiles of many varieties, along with submarines, patrol craft, and tactical aircraft that prowl the crumple zone, meting out punishment against U.S. forces bold enough to hurl themselves against it. If China’s antiaccess defenses grow powerful enough to impose unacceptable costs on the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Beijing might even hold the PLA Navy battle fleet in reserve. Why risk the fleet when you can fulfill your goals from shore and by sending expendable platforms fanning out in the near seas to dispense punishment? This is a strategy Clausewitz and Mao would endorse.

Mahan and the Fortress

The next two faces of Chinese sea power are those of Alfred Thayer Mahan and Théophile Aube. These two mariners foresaw maritime battle tactics that just now are coming into their own with the advent of long-range precision-guided armaments. Mahan decried Russian commanders’ habit of keeping the Russian Pacific Squadron under the guns of Port Arthur for protection during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Operating a “fortress fleet,” he maintained, represented a “radically erroneous” way of doing business in great waters. It circumscribed fighting ships’ radius of action while breeding timidity and defensive-mindedness in commanders.

But what if the rudimentary guns of Port Arthur had boasted the range to strike with precision throughout the Yellow Sea and Tsushima Strait, where the climactic naval engagements took place? Shore artillery would have afforded the Russian fleet protection against Japanese Admiral Heihachirō Tōgō’s superior fleet throughout the combat theater, and then who knows what would have happened? In all likelihood, the outcome would have been different had accurate shore fire extended hundreds of miles offshore rather than a scant few miles. No longer is fortress-fleet strategy erroneous. Indeed, it is an obvious choice for China.

Aube and the Small Boys

Admiral Aube was Mahan’s alter ego. He was a progenitor of the “ jeune école ” (young school), a 19th-century school of naval strategy that sought to counter oceangoing hegemons such as Great Britain’s Royal Navy. A second-rate naval power like Aube’s France could hope to shoo away the Royal Navy from offshore waters by harnessing asymmetric technology manifest in torpedoes, sea mines, submarines, and surface patrol craft. Such vessels and weapons were light and inexpensive, yet could offset battleships and cruisers in near-shore waters. That was good enough for a continental power such as France.

What was a good idea in Aube’s day resonates even more with today’s realities. Technology has super-empowered subs and surface craft—breathing new life into jeune école strategies. Merge young-school concepts with fortress-fleet concepts, and you have a defender that deploys shore-based armaments in concert with swarms of small, cheap, missile- and torpedo-armed craft to assail the nautical hegemon of our age—the U.S. Navy. Ergo, China employs offshore-waters defenses.

Roosevelt and the “Footloose” Fleet

Which brings us to the final face of Chinese sea power, Theodore Roosevelt. Speaking before the 1908 “Battleship Conference” at the Naval War College, President Roosevelt held forth on the symbiosis between land and sea power. For him these constituted mutually reinforcing arms of military might. Coastal gunners and small-ship crews should shoulder the burden of safeguarding seaports against seaborne assault. In so doing they would free the battle fleet to carry the fight to foes cruising the high seas. A joint division of labor, then, would render the fleet “footloose,” liberating it to “search out and destroy the enemy’s fleet.” That errand of destruction, opined President Roosevelt, represents “the only function that can justify the fleet’s existence.”

Such insights gladden Maoist hearts a century hence. TR and Mao—verily, strategy makes strange bedfellows! Like TR’s coastal artillery and light warships, a sufficiently dense thicket of PLA offshore defenses in the western Pacific would render the PLA Navy surface fleet footloose. And that is the goal of offshore-waters defense. PLA forces will safeguard the homeland mainly with fortress-fleet and jeune écoleplatforms—freeing the bulk of the surface fleet to mount a regular if not standing presence in remote waters.

Open-seas protection, then, is contingent on successful active defense of the Western Pacific. If Beijing comes to believe its crumple zone will give but not break, the leadership will feel at liberty to dispatch major task forces on errands outside China’s maritime periphery.

China’s Strategic Ideas

These concepts add up to a strategy that the United States and its Asian allies and friends dare not take lightly. Chinese sea power—not just a modern PLA Navy—is here to stay. What should U.S. Navy potentates do about it?

First, grapple with the ideas impelling Chinese maritime strategy, as elucidated here. Sound ideas from the past are coming of age as precision weapons and sensor technology mature. Clausewitz, Mao, Mahan, Aube, and Roosevelt—five faces of Chinese sea power—would fathom PLA commanders’ strategic design instantly.

Second, ensure the U.S. military fashions forces and counterstrategies to punch through China’s crumple zone. This is simple to say—but the simplest thing is difficult in contests of human wills, as Clausewitz points out.

And third, study Chinese operating patterns. If the PLA Navy takes to deploying a sizable fraction of its surface fleet on prolonged extraregional deployments, that will bespeak confidence in China’s active defense at home. A standing naval squadron in the Indian Ocean would supply convincing evidence that Beijing finds offshore-waters defense a satisfactory defense. It would thus constitute a formidable impediment for the United States and its allies and friends to overcome. How aggressively Beijing pushes for access to South Asian seaports will supply more clues. Ships cannot sustain themselves far from home for long without logistical support. The more basing rights Beijing negotiates, the greater the PLA Navy’s freedom of action overseas.

In short, how Chinese seafarers and aviators conduct themselves in the wider world will say much about CCP leaders’ faith in their crumple zone. It also could suggest methods and hardware for piercing it.

1. “ China’s Military Strategy, ” Chinese Ministry of Defense, 26 May 2015.

Professor Holmes is the inaugural holder of the J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College, and coauthor of Red Star Over the Pacific (Naval Institute Press, 2013). His next book is A Brief Guide to Maritime Strategy . He wrote a version of these remarks for a 2018 hearing of the congressionally chartered U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

No comments:

Post a Comment