By Ekaterina Zolotova

Chinese influence in Central Asia has increased markedly in recent years. For Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and even the relatively more closed-off Turkmenistan, China is becoming not only a major supplier of loans and investment but also a key trading partner. Some may interpret this as an indication that the influence of Central Asia’s historical benefactor, Russia, is diminishing. It seems, however, that Russia isn’t too alarmed by China’s growing influence in the region. That’s because, unlike China, Moscow’s interests in Central Asia are not just economic. Indeed, Russia has historical links to the region and security and political interests there, which will ensure that Moscow will be the dominant player in the region for years to come.

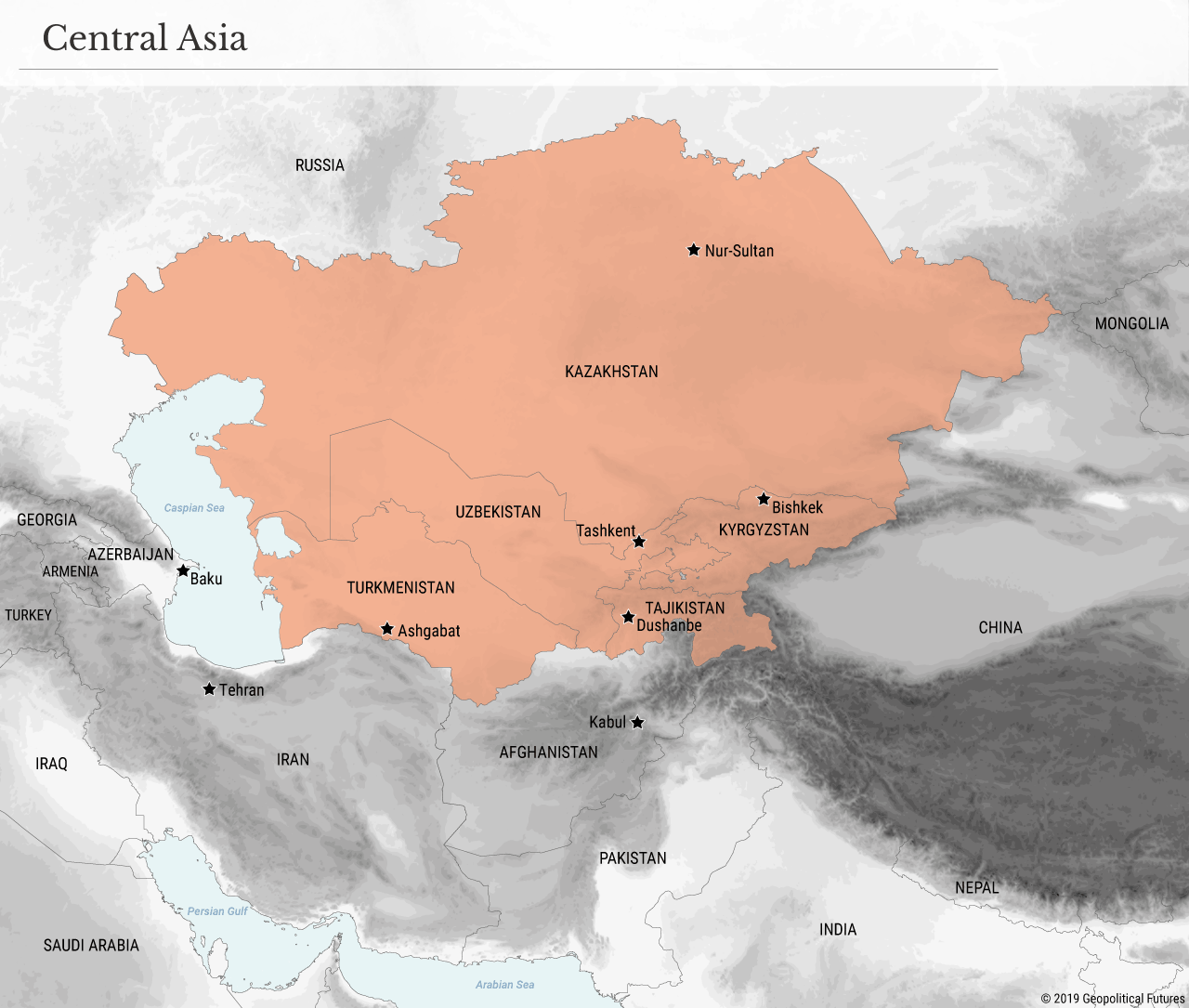

For Russia, maintaining influence in the post-Soviet Central Asian states is critical. These countries form a key buffer zone for Russia, separating the country from unstable areas of the Middle East and terrorist elements. Russia is concerned that terrorist and extremist influences could spread to its southern border and into the Caucasus through Central Asia and threaten to destabilize its southern and eastern regions.

Economic Influence

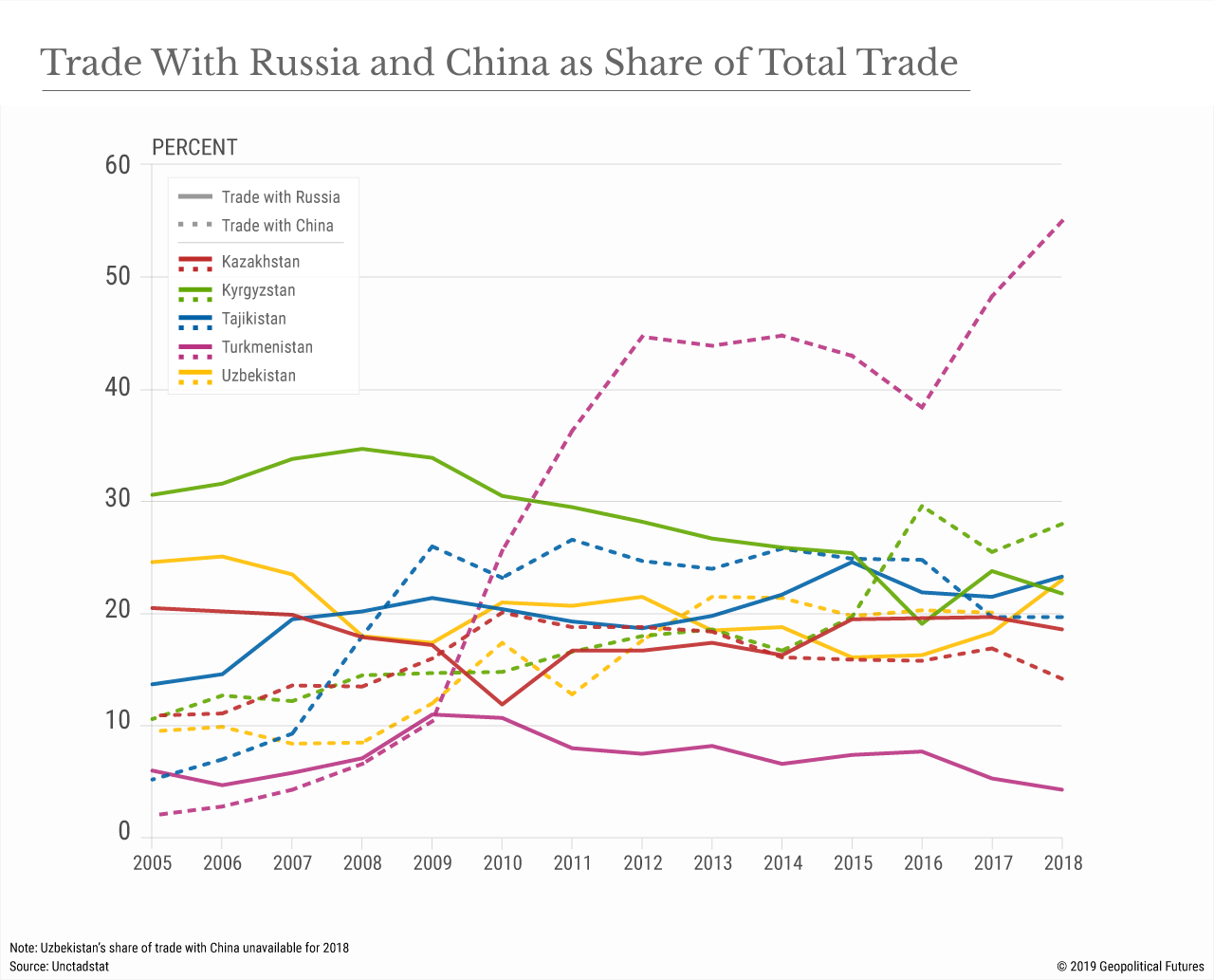

From an economic point of view, Russia looks at Central Asia as a region with potential. It sees Central Asia as a key route through which it could supply energy and other goods to growing markets like India, China and Pakistan, which, as they face increasing uncertainty from sanctions and the U.S. trade war, could become major consumers of Russian exports. But Moscow is facing increasing competition from Beijing in its historical sphere of influence. After the 2008 global economic crisis, Beijing began to more actively invest in and trade with the countries of Central Asia. China’s foremost interests in Central Asia are economic; Beijing sees these countries as a growing market for Chinese products, critical trade routes for the Belt and Road Initiative, and a source of needed natural resources. Chinese companies produce roughly 20 percent of Kazakh oil. More than 80 percent of Tajik gold deposits are operated by companies that receive Chinese capital, and more than 700 enterprises in Uzbekistan receive Chinese funding. China has also financed the development of Turkmenistan’s Galkynysh gas field and the construction of a gas pipeline through Kazakhstan. The estimated combined cost of these two projects exceeds $8 billion.

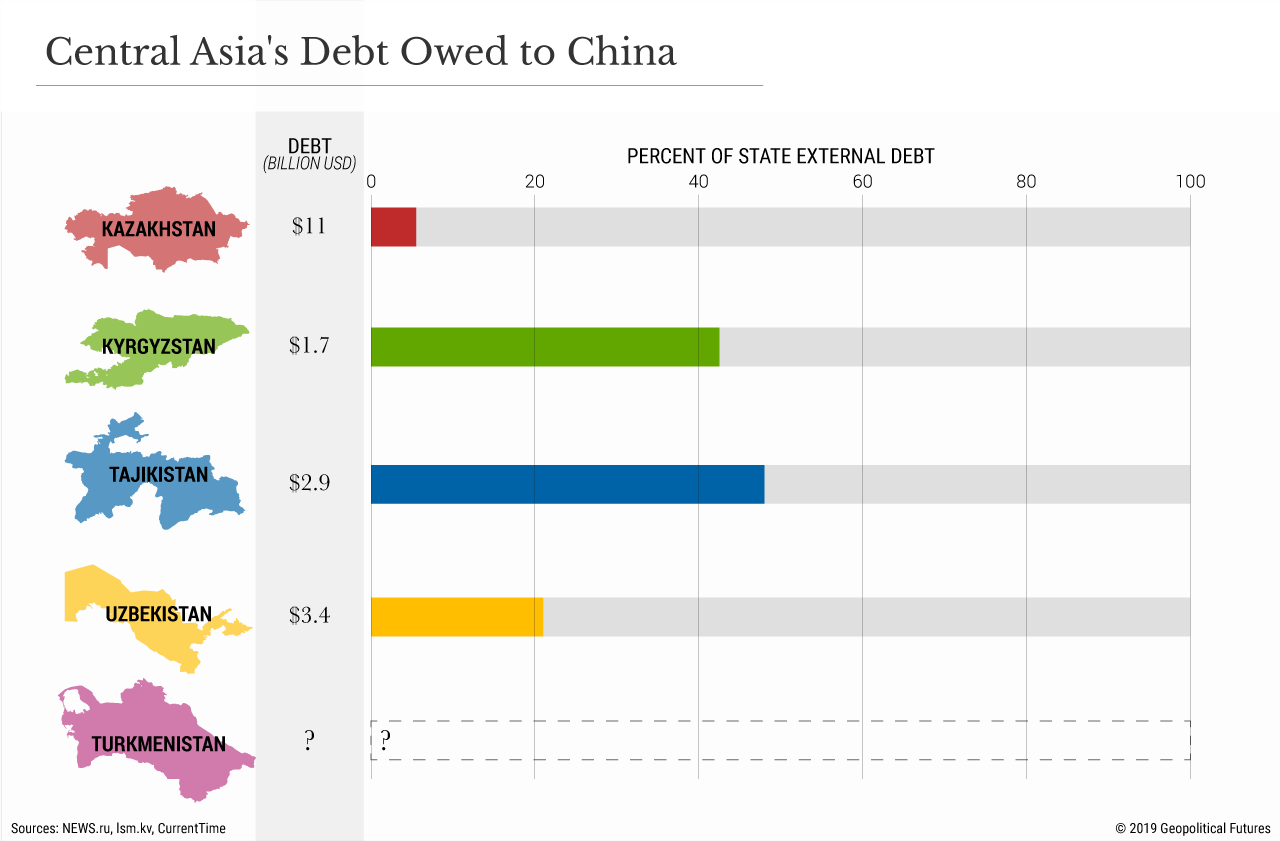

Central Asian countries now owe billions of dollars in debt to China. Uzbekistan alone owes $3.4 billion (21 percent of the state’s external debt); Tajikistan owes $2.9 billion (48 percent of its external debt); and Kyrgyzstan owes $1.7 billion (42.5 percent of external debt). This is raising concerns that Central Asian countries could become ensnared in so-called debt traps, compelling these states to agree to hefty political or economic concessions in order to pay off large loans they can no longer service. In 2011, for example, Tajikistan agreed to lease 1 percent of its territory to China. And Turkmenistan has supplied gas to China at a price three times lower than the market rate.

The growing Chinese economic influence here could challenge Russia’s historical role as the main benefactor for Central Asia. On economic grounds, Russia can’t really compete with China. Moscow is, however, maintaining a degree of economic influence by strengthening integration with Central Asia, particularly through the Eurasian Economic Union, which includes an integrated single market and common policies on several industries.

Ultimately, the two countries are unlikely to engage in open confrontation in the short term for a couple of reasons. First, Russia can’t afford a confrontation with China. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, China became the only major power that was willing to increase bilateral trade and economic ties with Russia; Russian foreign policy, after all, has long been oriented toward the east. Second, Russia has been a dominant economic force in Central Asia for decades. Its influence has been somewhat diminished as sanctions and economic troubles at home have eroded Russia’s ability to finance the region, but Central Asia and the Caucasus remain heavily dependent on Moscow in terms of both trade and remittances.

Strategic Interests

Moreover, although Russia continues to provide economic assistance to the region, this assistance stems from strategic interests rather than the promise of economic gain. Russia has written off hundreds of millions of dollars in Central Asian debt, including $240 million owed by Kyrgyzstan in 2017 and $900 million owed by Uzbekistan in 2016. For Moscow, developing good relations with these strategically located countries is more important than the potential economic benefit they could offer.

These countries form a key buffer zone for Russia, separating the country from unstable areas of the Middle East where terrorism and extremism are rife. Russia has a sprawling border with Kazakhstan that’s difficult to protect, and the borders between the Central Asian states are not well defended. The attack carried out by Islamic State militants on the Tajik-Uzbek border last week showed that terrorist organizations have already gained a foothold in the region. This is particularly concerning for Moscow because the militaries and security forces of Central Asian countries are highly dependent on Russia for equipment and training.

Since the formation of the Collective Security Treaty Organization in 1992, Russia has been the primary security guarantor for three Central Asian countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. (Uzbekistan was also part of the CSTO but has withdrawn its membership.) Russia has military bases and facilities in Tajikistan and an air base in Kyrgyzstan, and is helping to strengthen these countries’ own military capabilities. In October, it donated to Tajikistan 320 million rubles ($5 million) worth of military equipment and weapons including a radar station for monitoring airspace and modernized armored reconnaissance and BRDM-2M patrol vehicles. Also in October, the Central Military District’s press service announced the transfer of the S-300 Favorit anti-aircraft missile system to the Tajik-Afghan border. In addition, Uzbekistan has purchased from Russia Typhoon armored vehicles, delivery of which will begin sometime this year, as well as Russian-made BTR-82A armored personnel carriers, Tiger armored vehicles and a Sopka-2 radar station. Russia also plans to supply 12 Mi-35M transport and combat helicopters to Uzbekistan.

Though there has been much talk of China’s growing military presence in Tajikistan (it recently opened a new military base on the Tajik side of their shared border, for example, and held drills with the Tajik military in August), its security operations in Central Asia are mostly carried out within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Whereas Russia wants to remain the dominant military player in the region, China is content to take a backseat and avoid competing with Moscow for regional supremacy. Moreover, Beijing shares many of Moscow’s security concerns in Central Asia and therefore doesn’t feel threatened by Russia’s willingness to support Central Asian countries. China actually has more reasons to cooperate than compete with Russia, at least in the short term.

Despite China’s growing economic and military power, Moscow and Beijing don’t see each other as direct rivals in Central Asia, at least for now. There is indirect competition between the two countries, but their current interests and priorities rarely overlap in such a way that would push them into direct competition. China’s interests in the region are mostly economic, so it will be involved there only inasmuch as it can benefit economically. The deployment of Chinese troops in Tajikistan and the launch of counterterrorism drills with Tajik forces are connected to Chinese concerns over the security of its own investments in Central Asia and elsewhere. Russia, however, has deeper ties in Central Asia, and its interests are more strategic than economic. In tough economic times, it may see increasing competition for influence there, but no country has been able to match Russia’s presence and impact in the region.

No comments:

Post a Comment