Nations around the world are watching the U.S. election with almost the same intensity as Americans at home, and while they can't vote, they have passionate rooting interests.

During his four years in the White House, President Donald Trump has been accused of having a soft spot for the dictators of America's enemies. Do those countries return the love? As the 2020 election looms, the leaders and citizens of both America's allies and rivals are hoping for outcomes that may be surprising. With the exception of North Korea, most U.S. adversaries such as Cuba, Iran, China and Venezuela are hoping for a Joe Biden win, while America's allies are split. Germany, Japan and Australia would like to see Biden in the White House; India, Saudi Arabia, Israel and the U.K. hope Trump remains in power. The former vice president's chief asset appears to be his predictability: with few exceptions, even the nations hoping for a second Trump term think they can work with a Biden administration. And for some countries, like Russia, the optimal outcome is neither Biden nor Trump, but chaos.

Here's how other countries would vote if they could, and why.

Afghanistan: Trump Win

Afghanistan's President Ashraf Ghani and US President Donald Trump shake hands before a meeting at the Palace Hotel during the 72nd United Nations General Assembly September 21, 2017 in New York City BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty

Afghanistan's President Ashraf Ghani and US President Donald Trump shake hands before a meeting at the Palace Hotel during the 72nd United Nations General Assembly September 21, 2017 in New York City BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/GettyThe longest war in U.S. history was supposed to come to an end this year, a foreign policy win where his predecessors had failed. But continued violence, political infighting and fears about what Afghanistan's future could look like with the insurgent Taliban now at the table may have delayed these aspirations.

A senior Taliban leader appeared to endorse Trump, according to CBS News. "We hope he will win the election and wind up the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan," the official reportedly told the outlet.

Trump's decision to meet with the group that sheltered Al-Qaeda during 9/11 was controversial at home and in Kabul, where Afghan officials felt sidelined. The Taliban, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, refused to talk with the government until the historic peace deal signed in March after successive rounds of negotiations with the U.S. in Qatar.

Last month, the two rival factions held their first meeting, marking progress even as war continued across the country. Earlier this fall, Trump surprised observers and officials alike by announcing the U.S. would exit the country by Christmas. This pullout is the Taliban's leading condition in exchange for peace and promising to provide no quarter to Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State militant group (ISIS).

The current administration's next steps between now and Inauguration Day in January would ultimately determine what kind of policy former Vice President Joe Biden would inherit should he win the vote.

If the Taliban takes over, Biden said in July, the U.S. bears "zero responsibility." Biden has echoed Trump's talking point of ending "endless wars" including Afghanistan, and has sought an end to the conflict. Biden has shown no appetite for extending the U.S. military campaign in Afghanistan but he would inevitably have to talk to the Taliban.

The pace at which Trump wants to leave Afghanistan has raised concerns in Kabul, which has only just begun discussions with its bitter foe. The Taliban, for its part, has yet to renounce its strategy of targeting not only Afghan security forces but also officials and others associated with the current government in Kabul.

"We understand the fatigue in America, but withdrawal must be measured and strategic in order to preserve the gains that Americans and Afghans have sacrificed so much for," Afghan ambassador to the U.S. Roya Rahmani told Newsweek. "Without withdrawal being conditional, there would be a lack of incentive for the Taliban to fully commit to the ongoing peace process."

She called on the White House to make long-term commitments beyond the conflict and addressing Afghan society, including women's rights and the economy.

"The best way for the U.S. president to support the peace process is to be clear about which side is going to be a better partner for the US in the long-term; assess compliance to agreements based on empirical evidence and attention to detail; and capitalize on the investments made in the past 20 years and the large youth population in order to further our mutual interests," she said.

The Taliban declined Newsweek's request for comment.

Until these concerns are assuaged, the Afghan government is likely to look forward to a Biden presidency in hopes of stalling a hasty U.S. departure, even if ending U.S. engagement is a common goal among all parties involved.

- Tom O'Connor

Armenia: Biden, Azerbaijan: Trump

Local man Gambar looks at a residential building damaged by shelling during the ongoing military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, in the city of Ganja, Azerbaijan, on October 27, 2020. TOFIK BABAYEV/AFP/Getty

Local man Gambar looks at a residential building damaged by shelling during the ongoing military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, in the city of Ganja, Azerbaijan, on October 27, 2020. TOFIK BABAYEV/AFP/GettyIn a year already defined by a historic pandemic, ongoing wars abroad and dangerous socioeconomic unrest at home, a sudden, late September clash between South Caucasus rivals Armenia and Azerbaijan would seems to be on the periphery of U.S. interests.

The United States, however, has a duty to mediate as a member of the Minsk Group, along with co-chairs France and Russia. The troika was created the last time Armenia and Azerbaijan waged all-out war in the early 1990s and, as the two battle once again with their worst bloodshed since, countries are scrambling to implement a ceasefire.

But neither side will accept the status quo.

The conflict revolves around Nagorno-Karabakh, a 1,700-square mile plot led mostly today by ethnic Armenias but recognized internationally as part of Azerbaijan. Baku wants it back, while Yerevan believes it's up to its current inhabitants to chart their own course.

As one of Russia's few treaty allies, Armenia has traditionally enjoyed the Kremlin's support. But Turkey has weighed in heavily on the side of Azerbaijan, raising the stakes of any overt intervention, as Moscow and Ankara already butt heads over conflicts in Syria and Libya.

For the U.S., there is no clear predisposition.

The Trump administration, on the face of it, has made more public statements in favor of Armenia. The president himself remarked that Armenians "fight like hell" after being prompted by pro-Armenia fans during a recent rally, while Secretary of State Mike Pompeo criticized Turkish involvement and even expressed hope that "Armenians will be able to defend against what the Azerbaijanis are doing."

The administration recently censured Turkish involvement in Libya and, when Washington and Ankara were at loggerheads last year in Syria, U.S. officials threatened sanctions and, in an even more personal slight against Turkey, also threatened to acknowledge the Ottoman Empire's systematic killing of Armenians during and after World War I as a genocide, as Newsweek reported last October.

Ultimately, the White House retreated from its position, and walked back U.S. involvement as a Turkish incursion spearheaded by Syrian insurgents clashed with Pentagon-backed Kurdish fighters who also accused Ankara of ethnic cleansing.

Biden has raised the alarm on Trump's mostly sympathetic approach to Turkey. He's also pledged to recognize the Armenian Genocide, a move that would immediately threaten ties with Ankara.

Ultimately, both candidates have an interest in appealing to the influential Armenian diaspora in the U.S. (which includes Kim Kardashian West and award-winning singer-songwriter Serj Tankian, along with a long list of other celebrities and activists).

Azerbaijani ambassador to the U.S. Elin Suleymanov told Newsweek he has no electoral preference. When it comes to U.S. presidents enforcing a peace deal, however, "the most difficult situation for them is, of course, to be able to promote this agreement and remain impartial, given the pressure from Congress and the Armenian-American lobby."

Part of this lobby is the self-proclaimed Artsakh Republic, the Armenian-led Nagorno-Karabakh enclave with an informal presence in Washington pushing for greater U.S. involvement.

"We in Artsakh do hope that after the important electoral processes in the United States, the Administration will pay a greater attention to the situation in the South Caucasus," Robert Avetsiyan, the Artsakh permanent representative to the U.S., told Newsweek.

He called for the U.S. to recognize the Artsakh Republic and wield its clout in halting the conflict.

"We believe it is in the political and diplomatic power of the United States to have its crucial input in stopping the ongoing crimes against humanity and genocidal threats against the people of Artsakh, and bringing the long-term peace and stability to the South Caucasus," Avetsiyan said.

The Israel lobby in the U.S. has sided with Azerbaijan and supplies it with drones that have dominated the battlefield.

Given Trump's acquiescence to Turkey's more assertive regional role and his overt support for Israel, a Trump victory would likely score points for Azerbaijan, with the U.S. leaving regional powers to handle the situation in the South Caucasus. On the other hand, Biden's victory could see efforts to halt the Azerbaijani advance and potentially favor ethnic Armenian control over Nagorno-Karabakh.

- Tom O'Connor

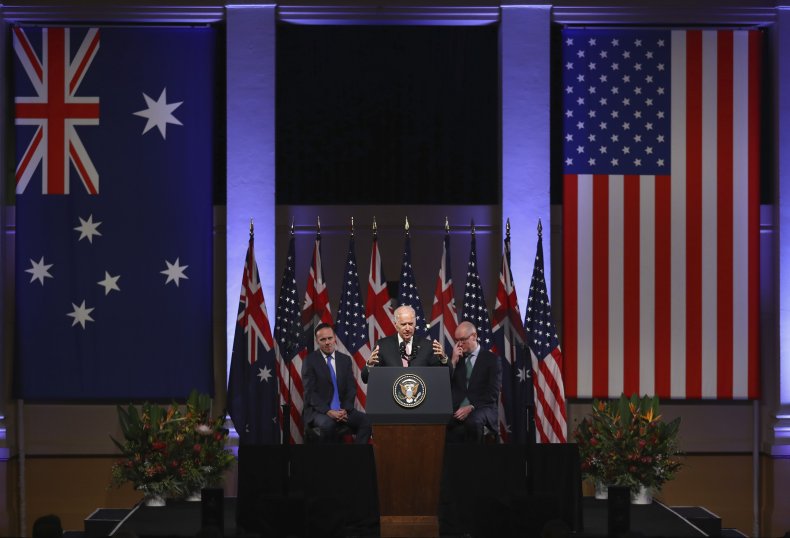

Australia: Biden

U.S. Vice-President Joe Biden delivers a speech on the future of the U.S.-Australia relationship at Paddington Town Hall on July 20, 2016 in Sydney, Australia Ryan Pierse/Getty

U.S. Vice-President Joe Biden delivers a speech on the future of the U.S.-Australia relationship at Paddington Town Hall on July 20, 2016 in Sydney, Australia Ryan Pierse/GettyAustralia is enormously vulnerable to Chinese aggression, and the country's defense and political elite agree with his tough stance on China.

Canberra is deeply concerned about Beijing's growing swagger in the South China Sea, where it has steadily built up military drills, disregarding overlapping claims from regional neighbors.

"Walking away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), imposing tariffs and trashing the WTO was bad from Australia's perspective but I think the intent is actually quite welcome as Australia gets nervous about an ever more assertive China," said Simon Jackman, CEO of the Sydney-based United States Studies Center.

A Biden presidency could ramp up anxiety among the Australian political establishment which feels the Obama-Biden administration was soft on Beijing.

"It was under Obama that China thought it could get away with militarizing the South China Sea islands," Jackman told Newsweek. "We may think Trump is mad for imposing tariffs," he said, "but grudgingly we accepted that he was the first American president to rattle their cage and we wanted Obama to do that."

The increased acrimony with China, however, has also raised fears in Australia, which would be among the first countries to feel Beijing's wrath, economic or otherwise, if tensions were to escalate further. Leaders hope a Biden presidency would rebuild America's global network of alliances instead of trying to browbeat China on its own, and would enact another trade agreement between the U.S. and a consortium of other countries including Australia. This would reduce the Australian economy's dependence on China.

"Using a less confrontational approach with China and working with Australia to diversify its trade relationships across other countries would be a win for the Australian economy and the stability of the Asia-pacific region," Rand Low, honorary fellow at the University of Queensland Business School, told Newsweek.

"Quietly, Australia would prefer a more multilateral approach and one with fewer wildcatting actions on trade," Jackman said.

- Brendan Cole

Brazil: Trump

U.S. President Donald Trump and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro attend a joint news conference in the Rose Garden at the White House March 19, 2019 in Washington, DC. Chris Kleponis-Poo/Getty

U.S. President Donald Trump and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro attend a joint news conference in the Rose Garden at the White House March 19, 2019 in Washington, DC. Chris Kleponis-Poo/GettyThe anti-establishment wave that brought President Trump to power is not a purely American phenomenon.

Elsewhere, populist figures from the left and right were propelled into office by disaffected voters spurned by globalization, chafing at widening economic inequality, and uncomfortable with the perceived erosion of traditional social and power hierarchies.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro is perhaps one of the examples that most chimes with Trumpism.

Bolsonaro has long courted controversy with remarks criticized as misogynistsic, racist and homophobic. He has expressed admiration for autocracy and dictatorship; was embroiled in nepotism and corruption scandals; and has made a point of dismissing the severity of the coronavirus pandemic, even after contracting it himself.

The Brazilian leader has battled with a range of scandals and poor approval ratings, though a recent cash stimulus amid the pandemic has buoyed his numbers. The next election is in 2022, so it may be that Bolsonaro is not in power for much of the next U.S. president's term.

Still, he will hope for another four years of Trump. Earlier this month, Bolsonaro said he would attend Trump's second inauguration "God willing."

Richard Lapper, an associate fellow at the U.K.'s Chatham House think tank, said: "The right-wing Bolsonaro administration will be rooting for Trump. Brazil has obtained precious little from the U.S. president but Trump is hugely popular among Bolsonaro's own voters.

"A Biden victory would weaken the cause of anti-globalism and 'illiberalism' worldwide, leave the Brazilian government more isolated and potentially under much more pressure to do more to clamp down on deforestation in the Amazon."

Roberta Braga, a deputy director at the Atlantic Council think tank, told Newsweek: "In working with the U.S., Brazil's priorities range from collaboration on post-COVID-19 economic recovery, as well as enhancing good regulatory practices, investment in infrastructure, and cooperation in addressing some of the region's most pressing challenges, including the crisis in Venezuela.

"Brazil and the U.S. will continue to look for opportunities to deepen collaboration on trade and investment, with the U.S. Ambassador in Brazil having affirmed he hopes to double trade between the two countries over the next five years. Brazil will also continue to look to the United States for support in its accession to the OECD."

- David Brennan

China: Biden

U.S Vice President Joe Biden attends a business leader breakfast at the The St. Regis Beijing hotel on December 5, 2013 in Beijing, China. Lintao Zhang/Getty

U.S Vice President Joe Biden attends a business leader breakfast at the The St. Regis Beijing hotel on December 5, 2013 in Beijing, China. Lintao Zhang/GettyPresident Trump's term has coincided with the back end of a strategic shift towards confronting China; a trend in motion for years and publicly acknowledged since at least Obama's "pivot to Asia."

There is bipartisan recognition in Washington, D.C. that China is America's next great strategic threat, and much of the country's foreign policy will have one eye on undermining Beijing and maintaining American hegemony.

The Trump administration has been hard on China, launching a wide-ranging trade war, confronting Beijing in territorial flashpoints, pushing back on human rights abuses, and taking on Chinese diplomatic, corporate and technological influence in the U.S. and abroad.

All this is supercharged by the coronavirus pandemic, which Trump has consistently pinned on Beijing.

China is both Trump's excuse and his strongest foreign policy attack line against Biden, whom he claims will sell the U.S. out to Beijing.

Trump's comments and policies have made it near-impossible for the D.C. foreign policy establishment to be other than tough on Beijing, so thereis not much daylight between the two candidates on China, though Trump's strategy will likely be more overtly aggressive and unilateral than Biden's.

"I suspect many in the Chinese leadership are torn," said Robert Manning, resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

"On the one hand, Trump's retreat from international organizations, trashing of U.S. allies, has been a gift to Xi. Trump's trade policies have backfired, with Chinese exports to the U.S. up, no major decline in trade deficit, and U.S. capital is flowing into China's more open financial markets."

China predicted much of this in 2016, said Jacques deLisle, an expert in Chinese law and politics at the University of Pennsylvania, which "inclines some in China—especially the more hawkish, nationalist, and perhaps overly confident elements—to see a second Trump term as a good thing."

But this all came with costs. Manning said: "The relentless China-bashing, crusade against Huawei and more broadly, Chinese tech and the downward spiral of a U.S.-China relationship in free-fall is dangerous."

DeLisle said: "Biden's upside is predictability and stability; his downside for China is that he may be far more effective—more regular and competent in policy making, more disciplined in implementation, and better able to cooperate with allies to bring pressure to bear on China.

"Trump's downside is the chaos and the Cold War rhetoric; the upside is that he is not very effective—erratic, shallow commitment to adverse positions on issues that matter to China, and alienates allies and potential allies."

Manning said the bottom line is China may prefer Biden "because they see him as fact-based."

"And though the broad consensus against China's economic and military transgressions would not change much, Biden would likely move to put a floor under the relationship and begin to define what 'strategic competitor' means and doesn't mean," Manning said.

Pacifying the economic and technological warfare of the Trump years—and GOP threats of broad "decoupling" with Beijing—will be high on China's list of priorities.

So too will be the continuing U.S. support for Taiwan—which China has vowed to absorb by force if necessary—and tensions in the South China Sea, touted as the most likely place for a U.S.-China military confrontation.

"Deepening enmity on both sides and race to the bottom increase fears of a drift toward military confrontation," Manning said. "Xi and the CCP are looking to stabilize what would be a redefined, more distant relationship."

DeLisle said this "sharpening, Cold War-like ideological tone in U.S.-China great power competition" is cause for concern within the CCP.

The Chinese "tend to be pragmatic, do not overly personalize the relationship, and know that they have to deal with the next president for at least four years," Manning said.

"So, while they will tailor their responses, their perceptions of whichever candidate wins, they have no illusions that it will result in major policy shifts, at least in the near-term."

- David Brennan

Cuba: Biden

Cuban Americans in Miami's Little Havana celebrate the death of longtime Cuban leader Fidel Castro on November 26, 2016. Rhona Wise/AFP/Getty

Cuban Americans in Miami's Little Havana celebrate the death of longtime Cuban leader Fidel Castro on November 26, 2016. Rhona Wise/AFP/GettyTrump's administration has systematically rolled back the historic progress made by former President Barack Obama in warming ties between Cold War-era foes Cuba and the U.S.

The past three-and-a-half years have seen a return to relations between Washington and Havana being framed by U.S. officials as part of an ideological struggle between democracy and socialism, or even communism, which Trump has vowed to eliminate from the Western Hemisphere.

Trump tightened the decades-long embargo on Cuba and expanded travel restrictions that had been lightened or eliminated by Obama. That was a blow to the island's tourism industry, which had benefited from a new flow of American tourists to the Caribbean island just 90 miles from the Florida coast. These measures have been tightened as a punishment for Cuba's backing of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, another leftist Latin American leader the U.S. has tried to oust.

Trump has championed his anti-Cuba efforts at politically charged gatherings that have included Cuban exiles and veterans of the failed CIA-backed effort to overthrow Fidel Castro in 1961.

Another four years of Trump would likely see an expansion of this pressure, aimed ultimately at the downfall of the Cuban Communist Party's rule, which has shown little sign of wavering despite an escalated U.S. siege. Trump's hardline policies have, however, inspired Cuba to build better relations to Russia and China, both of whom have expanded their footprints in Latin America in spite of U.S. warnings.

Raising the stakes of heightened tensions in this part of the world, Trump abandoned the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty that banned the class of mid-range weapons involved in the 1962 Cuba Missile Crisis, which brought Washington and Moscow to brink of a nuclear conflict.

When it comes to Cuba, Biden has an opposite record. Under Obama, Biden helped oversee the short-lived thaw between Washington and Havana; his wife, Jill, visited Cuba herself in the final weeks of the administration, attending a series of cultural events to strengthen the ties initiated by the president two years earlier.

Biden has vowed to reverse the Trump administration's policies, which he argues have not succeeded in loosening the Cuban Communist Party's grip but only increased the suffering of the island's population, who have been further cut off from the world's largest economy just 90 miles away.

Cuban officials in conversations with Newsweek have criticized the Trump administration's policies as antiquated and inhumane.

While no officials have explicitly endorsed Biden, Havana views a return to the Obama-era strategy that reestablished diplomatic relations and opened the door for more economic cooperation as a more beneficial path for both countries and their respective peoples.

This means Cuba is likely to see a Biden presidency as the better path.

- Tom O'Connor

The European Union: Biden

US Vice President Joseph Robinette "Joe" Biden, Jr is welcome by the President of the EU Council (Not pictured) prior to a bilateral meeting in the EU Council headquarters. Thierry Tronnel/Corbis/Getty

US Vice President Joseph Robinette "Joe" Biden, Jr is welcome by the President of the EU Council (Not pictured) prior to a bilateral meeting in the EU Council headquarters. Thierry Tronnel/Corbis/GettyTrump isn't a fan of the European Union (EU). He described Brexit as "a good thing" and believes that Europe "treats us [the U.S.] worse than China." It is no secret that neither French President Emmanuel Macron nor German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the leaders with most power in the EU, are fans of the president. Talks on trade agreements have stalled numerous times.

As a guide to how much of a priority Europe is for Trump, it took him 18 months in office to appoint an EU ambassador, who was then fired 18 months later. It is now a second job for Ronald Gidwitz, the U.S. ambassador to Belgium, in an acting role.

"The era in which we could fully rely on others is over to some extent," Merkel said in 2017 after a G7 Summit of world leaders. It was a clear signal that the U.S. was not operating on the global stage in the way it previously had. Europe must help itself, Merkel believes, and not look to the leader of the free world.

The EU is at a critical point, with Merkel stepping down in 2021 and COVID-19 fueling a global recession, putting presure on already-strained relationships across the EU.

"The lack of 'togetherness' from EU member states has sparked a tremendous anti-EU sentiment in the countries worst impacted," Dimitrios Goranitis, risk and regulatory advisory partner at financial consultancy Deloitte Romania, wrote. "Italy's anti-EU sentiment rose from 26 percent in November [2019] to 49 percent in March [2020]. This new crisis comes very close to Brexit and ongoing political instability due to rising populism in Italy, France and Eastern Europe, and it doesn't seem to bring member states together, but rather divide them. This time around, the EU is already too fragile to withstand more nationalism."

This nationalism has not been created by Trump but certainly been emboldened by it. Trump's remaining allies in the EU are in Poland and Hungary, with right-wing administrations not the biggest fans of EU alignment.

"If you understand the European Union as a centralized power the spirit and heart of which is provided by the institutions—Trump is not the best option," Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban said in September. "But if you believe that the European Union is nothing else but just a community of member states—Trump is OK, is by far the best."

It is this quandary that is at the heart of the future of the European Union. Biden, an ally of Merkel, Macron and a clear Europhile, would assist in the EU's goal to remain united under increasing pressure from the populist Right, an increasing debt crisis and disquiet from member states about how their voices are heard. He would also open the door to a free-trade agreement between the U.S. and the E.U. that has been difficult to forge under the current administration.

A second Trump term would do little to silence that disquiet. A fractured E.U. might be good for the U.S. in the short term but would be disastrous for Europe, breaking up the largest trading bloc in the world.

Enrico Letta, a former prime minister of Italy, said the EU faced a "deadly risk" from COVID-19 but that the biggest danger to its future was "the Trump virus."

"The communitarian spirit of Europe is weaker today than 10 years ago," he told the Guardian. If every EU country took the "our country first" strategy of Trump, he said, "we will all sink altogether".

- Alex Hudson

Germany: Biden

Vice President Joseph R. Biden (L) and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (R) listen while German Chancellor Angela Merkel addresses a joint session of the U.S. Congress on Capitol Hill November 3, 2009 in Washington, DC. Bundesregierung/Steffen Kugler-Pool/Getty

Vice President Joseph R. Biden (L) and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (R) listen while German Chancellor Angela Merkel addresses a joint session of the U.S. Congress on Capitol Hill November 3, 2009 in Washington, DC. Bundesregierung/Steffen Kugler-Pool/GettyNo traditional U.S. ally has been as discomfited during the Trump years as Germany. The president has been critical of Germany for its failure to meet NATO spending targets, its natural gas pipeline deals with Russia, its refusal to toe the U.S. line on Iran, and its trade practices. Germany is also the central pillar of the European Union, a bloc Trump considers an economic rival and a potential target for more punitive tariffs in a second term.

The main political players in Germany will certainly be hoping for a Biden victory. The former vice president has promised to focus on diplomacy and America's traditional alliances, something Germany will be central to.

Most European nations likely prefer a Biden presidency, Hans Kundnani of the British Chatham House think tank told Newsweek, though it is a sliding scale. "I think Germany is on the extreme end in terms of wanting Biden," he said.

Climate change, the Iran nuclear deal, tariffs—Biden will align closer with Germany on all of these issues than a second Trump administration, Kundnani said. "Their instinct is going to be to work really closely with Germany," Kundnani said of Biden's team.

But there are some issues where U.S. and German interests will still diverge. Like Trump, Biden has already said he is opposed to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline with Russia.

German politicians have been broadly supportive of the project, keen on more cheap Russian gas to fuel German industry despite the potential security implications. This includes those vying to become the next leader of Chancellor Angela Merkel's Christian Democratic Union party in December, and perhaps replace her as chancellor in 2021.

The more hawkish Norbert Rottgen has been the only candidate consistently pushing back against Nord Stream 2, though right-winger Friedrich Merz called for a freeze on construction following the poisoning of Russia dissident Alexei Navalny in August.

Difficult questions will also remain about German military spending and the role of U.S. forces in European security. The long-term trend is a U.S. pivot to Asia and a more targeted deterrence of Russia in Europe, focused on smaller, more mobile, more advanced units in eastern Europe.

The China question will influence the U.S.-Europe relations, whoever is in the Oval Office. With Trump, the U.S. is likely to try and bully its allies into line. A Biden administration is more likely to pursue multilateralism.

If Trump wins again, it may strengthen the hand of those pulling away from Germany's traditional reliance on American military protection and towards more European strategic autonomy—something Trump has railed against even while lamenting the financial cost of defending the continent.

- David Brennan

India: Trump

US President Donald Trump (L) shakes hands with India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a joint press conference at Hyderabad House in New Delhi on February 25, 2020 PRAKASH SINGH/AFP/Getty

US President Donald Trump (L) shakes hands with India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a joint press conference at Hyderabad House in New Delhi on February 25, 2020 PRAKASH SINGH/AFP/GettyFew leaders have exploited Trump's love for crowds and adulation as well as Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who organized a huge love-in for the president during his first visit to India last year and who has made a point of lauding his personal relationship with Trump.

Modi is a deft career politician who has been a prominent political figure in India for years, rising through the ranks of his Bharatiya Janata Party. But the two men have much in common.

Both are populist right-wingers who promised their supporters an economic boost and a revival in national pride. Both lean on religion and exploit racial and religious divisions to animate their base and deflect criticism. Both espouse democracy and liberty while—critics charge—eroding the institutions that protect them.

Another term of Trump would help Modi in his principal foreign and domestic challenges, Irfan Nooruddin of the Atlantic Council told Newsweek. The Trump administration's campaign against China has seen the White House draw closer to New Delhi, which is embroiled in its own long-simmering border conflict with Beijing.

New Delhi has signed new intelligence-sharing agreements and new weapons deals with the U.S., and is positioning itself to take advantage of American and Western companies reducing their footprint in China and looking for alternatives. Modi will be looking to leverage a second Trump administration's China campaign to India's benefit.

"The other reason is that Trump doesn't care in the least whether India tramples upon democracy, civil liberties, religious freedoms at home," Nooruddinn said, "Modi expects the Trump government will give him a free hand on those, where the Democrats in Congress have shown a willingness—and in fact, a propensity—to ask pretty hard questions about some of those concerns to the Indian government in ways that they are pretty sensitive about."

The more extreme elements of Modi's Hindu nationalist following have engaged in violence against Muslims and Christians, encouraged—the BJP's critics say—by Modi's nationalist rhetoric. Opponents have condemned a new citizenship law they say marginalizes India's 172 million Muslims. Meanwhile, the Muslim-majority northwestern state of Kashmir remains under a security lockdown and communications blackout, an attempt to quell protests against Modi's revocation of the state's special status that long offered the disputed state limited autonomy.

New Delhi may take a tough line on any Democratic interest in India's domestic problems.

"I think the Modi government would go back to an old, well-established playbook that precedes Modi and say: 'We have domestic political issues, we are a functioning democracy. Don't poke your nose where it doesn't belong."

But a Biden administration would also be looking to contain China, so Modi's government could still stand to gain from a Democratic win from a foreign strategic perspective.

Either way, Modi will be looking to the U.S. to upgrade India's armed forces—especially its navy, enabling better power projection into the Indian Ocean, where China is increasingly present—and secure new trade opportunities amid the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic.

"The economic hit India has taken—they're still measuring the true costs of it, and will be for a while—but there's no question that anything that shows that there's going to be more U.S. investment in India, plugging into more into the global supply chains of American companies, they would love for something to come out of that."

- David Brennan

Iran: Biden

No deal? Iranian President Hassan Rouhani walks past a portrait of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Tehran, on February 16, 2020. - ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images

No deal? Iranian President Hassan Rouhani walks past a portrait of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Tehran, on February 16, 2020. - ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty ImagesWashington and Tehran's decades-long tensions took a brief break in 2015 with the advent of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), a milestone nuclear agreement involving both the United States and Iran, as well as China, France, Germany, Russia and the United Kingdom.

Forged under President Barack Obama, it was vehemently opposed by Donald Trump as a private citizen, a candidate, and then as president, when he left the accord in 2018. Ever since, the U.S.-Iran relationship has been defined by unrest across the Persian Gulf and deadly tensions in the Middle East, with an impasse at attempts to rekindle diplomacy with Iran.

While the Trump administration has repeatedly said its door was open for talks, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has insisted that the U.S. must first return to the nuclear deal and lift its unilateral sanctions. That, almost certainly, will not happen in a second Trump term.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, who was Obama tasked to help sell the JCPOA to skeptical Republicans, has vowed to return to the agreement, while still actively opposing Iran's support for foreign militias and its pursuit of advanced ballistic missile technology.

But some Trump administration actions are irreversible.

Perhaps the most significant is the U.S. killing of iconic Revolutionary Guard Quds Force commander Major General Qassem Soleimani, which some Iranian officials compare to the infamous CIA-backed coup that reinstalled the shah's absolute monarchy in 1953, an event that helped fuel the 1979 Islamic Revolution and subsequent U.S. embassy hostage crisis.

A U.S. largely isolated among the international community in its support for heavy economic restrictions against Iran has far less leverage than it did under Obama, whose multilateral approach was embraced by most nations, with the notable exceptions of Israel and Arab Sunni Muslim monarchies like Saudi Arabia.

Iranian officials have told Newsweek that their country remains neutral in the election and that, even if in the event of a Democratic victory, the winner would likely face an intensive effort to adopt more hawkish views against the Islamic Republic.

Ultimately, they saw a need for faithful implementation of the JCPOA to rebuild trust broken by Trump's exit.

This trust may be hard to earn, however, as Iran is set to hold its own national elections next June, giving Biden only months before Rouhani's second term ends and a newcomer takes his place.

All indications are that the Trump administration's foreign policy has fueled a strong aversion to dealing with the West among increasingly influential Iranian hardliners. While Biden may be Iran's best bet to stabilize the soaring tensions between the two countries, a return to the pre-Trump status quo is unlikely and an even more difficult path to detente may lie ahead.

On balance, a Biden presidency would appear to offer Iran the best chance for a reinvigorated JCPOA, with the return of the U.S. to the treaty, and a path back to greater participation in the world economy.

-Tom O'Connor

Israel: Trump

Prime Minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu and U.S. President Donald Trump walk through the West Wing Colonnade prior to the signing ceremony of the Abraham Accords on the South Lawn of the White House on September 15, 2020 in Washington, DC. Alex Wong/Getty

Prime Minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu and U.S. President Donald Trump walk through the West Wing Colonnade prior to the signing ceremony of the Abraham Accords on the South Lawn of the White House on September 15, 2020 in Washington, DC. Alex Wong/GettyIf the old adage about Israel being America's 51st state were true, Trump would carry the Jewish state in a landslide—in stark contrast to the 70 percent Biden support projected among America's own Jewish voters. Israel might be politically divided, with three successive elections ending in gridlock and with the government currently shared in a fraught emergency coalition between Benjamin Netanyhu and his erstwhile challenger, Benny Gantz. Netanyahu himself might be at a political nadir, trapped between a looming corruption trial and persistent nationwide demonstrations galvanized by his government's catastrophic mishandling of the economic crisis engendered by the coronavirus pandemic. But on one issue, the majority of public opinion in Israel and its government align: Israel falls definitively in the Trump camp in the 2020 election.

The reasons are not difficult to discern. Trump lavished extraordinary attention on Israel from the moment of his election. Much is made of which state a new president chooses for his first overseas trip, but Trump rushed to Israel within days of his victory, weeks before being inaugurated. The "Deal of the Century" championed by his son-in-law, adviser (and Netanyahu family friend) Jared Kushner was easily the most seductive outline of a peace agreement ever put on an Israeli leader's table. It adopted Netanyahu's mantra of "economic peace" and reduced independent Palestinian statehood to enclaves with far less autonomy than American states enjoy vis-a-vis their own federal government. One of the main "carrots" dangled in front of Israel in earlier peace plans—U.S. recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital—was given away with no return and with much fanfare.

In contrast to Obama, who began his presidency with a failed attempt to pause the construction of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, Trump's ambassador to Jerusalem is himself intimately linked to the settlement movement. And for the first time, however briefly, the dream of unilaterally annexing the territories Israel didn't manage to secure in the War of 1948—without entertaining voting rights for their Palestinian population — seemed within Netanyahu's grasp. Perhaps most importantly for Netanyahu, in Trump he found a president almost as ferocious as he in opposing Iran. The Obma deal that Netanyahu spent much of his last few terms campaigning against has been cast aside, and although Trump has stopped short of going to war with Iran, the underpinnings of a regional Sunni-Israeli-American alliance against Tehran are now firmly in place. Thanks to the flurry of treaties known as the Abraham Accords, Israel now has above-board relations with more countries than ever before in its history.

The Israeli public is also solidly pro-Trump, consistently giving him higher approval ratings there than in his own country. That's not so much because of all the boons delivered to Netanyahu—neither Iran nor the somewhat abstract question of Jerusalem's diplomatic importance top the list of Israelis' everyday concerns, while the Palestinian issue hasn't dominated a general election since the early 2010's. But in a nation deeply allergic to even the best-intended criticism, Israelis have put Trump down as firmly "on our side": he offered no critiques, made no demands, heaped Israel with praise and, despite a close shave or two, managed not to spark a regional war.

"Israel is not a deeply polarized society, outside of the narrow Netanyahu question," Daniel Levy, a former Israeli negotiator and president of the Foundation for Middle East Peace, told Newsweek. "There's actually a deep consensus around the broader narrative of how Israel understand the region and the world, and around the preference for Trump."

Still, even Israelis—beginning with their prime minister—are beginning to adjust to the possibility of a Biden presidency. The overall assumption is that Biden will have plenty on his plate domestically and will be in no rush to wade into the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He might try and reset the rapprochement with Iran, but dynamics set in motion by Trump's first years make it even more of an uphill battle. And this is where Israel's own political divide comes into play: moderates, represented by Benny Gantz, are a seat or two away from a majority coalition, and they would certainly prefer to work with Biden, if only because of how tightly allied Netanyahu and his party are with Trump's administration, Levy said. Biden, meanwhile, is seen as a traditional pro-Israel Democrat: "they don't really buy the argument about the entire Democratic party turning anti-Israel."

"The fear for Netanyahu is not so much getting Biden as losing Trump," Levy added. "The hard right doesn't want to lose what they gained under Trump, and they do feel threatened by a Biden presidency because he won't go along with projects like annexation, and because Biden might appoint people who distrust and dislike Netanyahu since their days in the Obama administration."

At the same time, the Israeli prime minister is already positioning himself to engage a potential Biden administration.

Famously interventionist when it comes to domestic American politics, Netanyahu himself hung back on the sidelines in this election; after needling Obama throughout his presidency and praising Trump throughout his first term, the Israeli leader is hedging his bets.

On Friday before last, announcing the normalization of relations between Israel and Sudan via publicly staged telephone call with Netanyahu, the American president all but begged the prime minister for an endorsement. "Do you think Sleepy Joe could have made this deal, Bibi? Sleepy Joe?" Trump asked, looking expectantly at the cameras. After the briefest of pauses, Netanyahu demurred. "Uh ... well ... Mr. President, one thing I can tell you is we appreciate the help for peace from anyone in America," he replied, separating "any one,",for emphasis. And only then, almost as an afterthought: "We appreciate what you've done, enormously." Against the backdrop of a White House beset by a poor prospect for reelection, this sounded almost like a goodbye.

- Dimi Reider

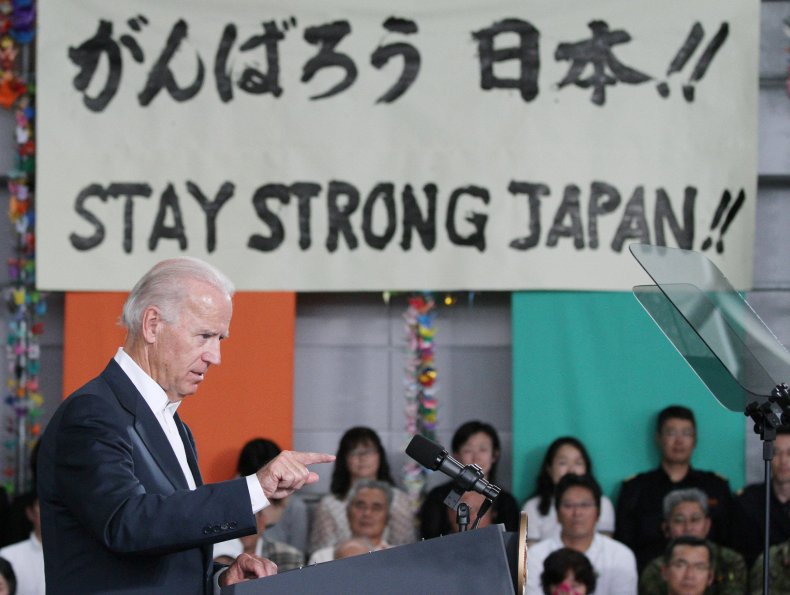

Japan: Biden

US Vice President Joe Biden (L) delivers a speech upon his arrival at Sendai airport in Natori, Miyagi prefecture on August 23, 2011. JIJI PRESS/AFP/Getty

US Vice President Joe Biden (L) delivers a speech upon his arrival at Sendai airport in Natori, Miyagi prefecture on August 23, 2011. JIJI PRESS/AFP/GettyJapan has long been a key ally in a difficult East Asian region. America's "pivot to Asia" will require support from regional allies such as Japan and South Korea to face down an increasingly assertive China and a nuclear-armed North Korea.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe resigned in August due to health problems and now Japan is settling into the leadership of Yoshihide Suga. The new administration will seek to build on Japan's existing alliance with the U.S. while keeping the door open to China and its riches.

John Nilsson-Wright, an expert in East Asian politics at the U.K.'s Chatham House think tank and a senior lecturer at the University of Cambridge, told Newsweek that a Biden victory would better suit Tokyo's goals for the next four years.

"A transactional Donald Trump has undermined the consensus surrounding the U.S.-Japan alliance relationship—particularly the stress on mutuality and shared interests on trade, security and support for international institutions—and which has been embraced by most postwar U.S. administrations and their Japanese counterparts," Nilsson-Wright said.

Abe pushed for closer ties with Trump, but his flattery campaign largely failed. Washington's "push for dramatically-increased host nation support from Tokyo, its zero sum approach to trade negotiations, and its erratic posture on relations with North Korea have all led to a souring in private by senior Japanese officials towards Trump," Nilsson-Wright said.

"For these reasons, and in particular because of Biden's pledge to restore normal alliance ties, Tokyo will favor a victory for the Democrats next week, and be encouraged by a return to a more normal and predictable bilateral relationship."

Tokyo's priorities include combating the Chinese challenge while retaining economic ties with Beijing, including involvement in its controversial Belt and Road project.

Japan also hopes to consolidate multinational collaboration in the Quad—a group of allies including itself, the U.S., India, and Australia—and push the Free and Open Indopacific initiative, while working to restore the clout of international institutions like the UN, G20 and G7.

Nilsson-Wright noted, though, that Tokyo would prefer to keep its historic rival South Korea out of the latter.

Containing North Korea may produce closer U.S.-Japanese security cooperation—for example, on improving Japan's missile strike capability—though Tokyo is keen to maintain some dialogue with Pyongyang, Nilsson-Wright said.

Tokyo will also want to bring renewed focus to climate change and the Paris Agreement, "a posture that resonates with Suga's commitment to carbon neutrality by 2050," Nilsson-Wright said.

A second Trump term would leave Japan facing four more years of tricky U.S. ties.

"This will be less of a pivot, and more an effort to use closer security cooperation to buy off transactional trade pressures," Nilsson-Wright said.

"Suga will seek to double down on Abe's charm offensive with Trump but it is less clear this will work in an emboldened and even more unrestrained and unilateral America."

- David Brennan

Mexico: Trump

U.S. President Donald Trump walks to the Rose Garden with Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador at the White House July 8, 2020 in Washington, DC. Win McNamee/Getty

U.S. President Donald Trump walks to the Rose Garden with Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador at the White House July 8, 2020 in Washington, DC. Win McNamee/GettyMexico has been an integral part of Trump's "Make America Great Again" vision, serving as the bogeyman for his base and the punching bag for the president's nativist and protectionist agenda.

The best-known policy bid to build a border wall along the entire southern border—and to have Mexico pay for it—has failed. Former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon is even facing fraud charges over a private fundraising campaign to support the divisive project.

But Mexico is also party to Trump's re-negotiated version of NAFTA—the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement—which the White House claimed as a victory for American workers and a reversal of long-term globalization trends that saw corporations shift manufacturing outside America in search of cheaper labor.

Center-left anti-establishment President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has managed to avoid the kind of conflict with Trump that some observers predicted after his landslide electoral victory in 2018. His government has taken steps to ease the immigration pressure on the U.S. southern border and went along with USMCA talks. Trump has given Obrador a largely free hand at home, provided his southern counterpart help at the border.

As to whom Obrador—colloquially known as AMLO—wants to win in the U.S., Duncan Wilson, the director of the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center think tank, told Newsweek: "This is a fascinating question with a complicated answer."

"AMLO himself would prefer a second Trump term because he believes that, by satisfying Trump's demands on immigration, he secures non-intervention by Trump on all other issues regarding investor relations and especially the energy sector," Wood said. "This may well be an erroneous assumption in a second Trump term."

"However, when we examine Mexican public opinion, a different answer is found. Sixty percent of the Mexican public has a negative opinion of Trump, a number that has dropped from 69 percent in 2017, but which reflects the damage that was done to bilateral relations in the campaign of 2016 and in its immediate aftermath."

"The key priority of the AMLO administration is avoid conflict with the U.S. government and to avoid U.S. pressure to change course on issues such as the economy, energy regulation and regulation of the pharmaceutical industry," Wood said.

If Biden wins, Obrador's administration will have to quickly pivot to working with the Democrats. A Biden win may bring U.S. opposition to Obrador's efforts to sideline private firms from the country's energy and pharmaceutical sectors. A Democratic administration would also likely mean less tension and fewer human rights abuses at the border.

"We need to work in partnership with Mexico," Biden said after Obrador visited Washington in July. "We need to restore dignity and humanity to our immigration system."

Mexico may be able to scale down its national guard deployment along the frontier—put in place to soothe Trump's frustration at the number of immigrants making it into the U.S. But this would likely come with more scrutiny of the human rights abuses and corruption on the Mexican side of the border from Democrats more concerned with such issues than the Trump administration.

"There will be an urgent need for bridge-building with the Biden camp as there has been almost no contact until now and there was an awkward omission in AMLO's visit to D.C. in July, when he didn't meet with any Democrats," Wood said.

- David Brennan

Nigeria: Trump

Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari (L) and U.S. President Donald Trump shake hands at the conclusion of their a joint press conference in the Rose Garden of the White House April 30, 2018 in Washington, DC. Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari (L) and U.S. President Donald Trump shake hands at the conclusion of their a joint press conference in the Rose Garden of the White House April 30, 2018 in Washington, DC. Chip Somodevilla/GettyWhen President Donald Trump wanted to stop immigrants coming to the U.S. from "shithole countries," as he described them, he imposed a travel ban on countries including Nigeria, the most populous Black nation in the world.

The African Union made up of 55 nations said the remarks were "clearly racist" and the restrictions, arriving just before COVID-19 took the world's attention, were widely criticized. It followed a concerted campaign to limit Nigerian entry into the U.S., with visa price-hikes and bans.

Despite Trump's strong line against Africa, and anti-Black Lives Matter-protest rhetoric more generally, the Nigerian public as a whole still loves him and would welcome a second term. Around 60 percent of Nigerians think Trump will "do the right thing regarding world affairs," according to the Pew Research Center. One important reason: Nigeria has one of the largest Christian populations in the world, including a large number of Evangelical Christians.

"I pray for Trump because I see him as the almond tree," Venerable Emeka Ezeji, a vicar and archdeacon in the Missionary Christ Anglican Church in Nigeria, told Newsweek by email. "This means he's a sign. If he wins this election, God is giving America and the world more time. If he loses, it means there is no time and speaking apocalyptically, looking at the political ideology of the Democrats, you discover they are working against the inerrant word of God—they promote abortion, same-sex marriage, while the Republican Party are pro-life purely conservative."

Of course, there is no "one" opinion in Nigeria, particularly with the country being split so evenly between Muslim and Christian communities. But most stand behind Trump, even defending some of his criticism of their own country.

"Some think that Trump has used very hard words on Nigeria and Africa but are they not true?" Ezeji says. "In African nations, the leaders are selfish, corrupt and presidents who want to remain in power till they die with nothing to show for it."

Economists argue that Nigeria has more to gain from a Biden presidency, with borders likely to be more open and a less hawkish approach to the oil industry. Crude oil still accounts for around 80 percent of Nigeria's exports and is hurt by Trump's desire to keep prices low, but Nigeria is going through a turbulent time economically in any case.

Biden has been drawn on the recent protests against Nigeria's Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) as people were shot dead, saying that the U.S. "must stand with" protesters. Trump has not been drawn on this issue but that is unlikely to change the support for him.

Nigeria does not allow or recognize LGBT+ rights and does not allow abortion unless the mother's life is in danger; a majority of Nigerians say a man is the head of the household, and stringent drug laws with long prison sentences are in place: familiar views for the more traditional end of the Republican party and a number of Trump's policy aspirations.

When Nigerian head of state's Muhammadu Buhari became the first president from sub-Saharan Africa to visit Trump's White House, Trump made a promise that the Nigerian tourist board could only dream of: "I'd like very much to visit Nigeria," Trump said. "It's an amazing country and in certain ways I heard from the standpoint of a beauty of a country, there's no country more beautiful, so I would like to."

Buhari will be hoping that Trump wins and visits before the Nigerian president steps down in 2023. But with the current protests and instability in the country, it is unlikely that whoever wins the presidency will be visiting any time soon.

- Alex Hudson

North Korea: Trump

US President Donald Trump and North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un talk before a meeting in the Demilitarized Zone(DMZ) on June 30, 2019, in Panmunjom, Korea. Brendan Smialowski / AFP/Getty

US President Donald Trump and North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un talk before a meeting in the Demilitarized Zone(DMZ) on June 30, 2019, in Panmunjom, Korea. Brendan Smialowski / AFP/GettyTrump's journey on North Korea has been perhaps more unexpected and contradictory than any other area of his foreign policy. The president started his term threatening "fire and fury" against Pyongyang, and, according to close aides, coming closer to war than the public ever realized.

But within months Trump was posing for photos alongside dictator Kim Jong Un at the first-ever summit between American and North Korean leaders in Singapore. The meeting produced grand but vague promises of North Korean denuclearization, sanctions relief and a new relationship between long-time enemies.

This has since collapsed back into stagnation and aggressive rhetoric. Kim has honored his moratorium on ICBM and nuclear warhead tests, but research is continuing on both. Pyongyang is now thought to be able to hit the continental U.S. with nuclear-tipped missiles, despite Trump's claim the country is no longer a nuclear threat.

North Korea would prefer another four years of Trump to a Biden presidency. "North Korea clearly favors Donald Trump—there is no doubt about that at all," said Harry Kazianis, senior director of Korean studies at the Center for the National Interest.

"Trump, at least from their perspective, would be the most willing to compromise on a deal that would see their international isolation lessen enough to help ensure their survival. Believe me, there is no love between Trump and Kim, but I think Pyongyang realizes that Trump is the best chance to see some sanctions removed."

U.S. sanctions, natural disasters and the coronavirus pandemic have all squeezed Pyongyang, even though Kim continues to deny COVID-19 cases in the country. During his speech at a major military parade, Kim cried and apologized to North Koreans for his regime's lack of success.

"North Korea has been hammered by three typhoons, economic sanctions, food insecurity issues impacting something like 60 percent of the population and a self-imposed economic blockade to ensure COVID-19 does not come en masse into the DPRK," Kazianis said. "What North Korea needs, and I would say soon, is some sort of economic help. And that means what Pyongyang wants from America is sanctions relief."

Biden would likely opt for a multilateral approach on North Korea, along with working-level diplomacy, advisers have said. He's unlikely to go in for the kind of personal relationship than Trump tried so keenly to cultivate. Biden will push for denuclearization and refuse to reward Kim unless progress is made.

This "strategic patience" approach will hark back to the Obama years. It won Biden little love in Pyongyang, and North Korea has dismissed the candidate as a "rabid dog" that deserves to be beaten to death.

"If Joe Biden wins the election, what North Korea does next to adapt to the new situation depends on its internal stability," Kazianis said.

"If Kim is starting to feel squeezed, he will do what all North Korean leaders have done in the past—respond to pressure by pushing back with pressure of his own. And that means a ramp-up of missile tests followed by a big ICBM test while team Biden goes through a North Korea policy review from January to March of next year if elected."

"While Biden won't respond with threats of nuclear war like Trump, I am sure the new administration will push back with a new round of sanctions, guaranteeing we will be back to the same old dangerous escalatory cycle we see every few years."

- David Brennan

Palestinian Authority: Biden

US Vice President Joe Biden (L) and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas shake hands during their meeting at the Presidential compound on March 10, 2010 in Ramallah, West Bank. Atef Safadi - Pool/Getty

US Vice President Joe Biden (L) and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas shake hands during their meeting at the Presidential compound on March 10, 2010 in Ramallah, West Bank. Atef Safadi - Pool/GettyFormer President Obama's administration ended on a cold note with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netyanhu. Already at odds over Israel's greatest ally endorsing the Iran nuclear deal, the Israeli leader criticized the United States' decision to abstain and not veto a United Nations resolution condemning Israel's developments on occupied Palestinian territory.

When President Trump came to office in 2017, he immediately found a friend in Netanyahu, and quickly made a foe of the Palestinian Authority.

The Trump administration's unprecedented decision to recognize the contested holy city of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and move the U.S. embassy there enraged Palestinians and much of the international community. It also led Palestinians to rethink the historic role the U.S. held as mediator in the decades-long conflict.

As a result, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas has considered Trump's so-called "deal of the century" for Israeli-Palestinian peace dead on arrival.

The agreement offered a potential path to formal Palestinian statehood along with billions in investment, but contained major territorial concessions that would further fragment the areas controlled by Palestinians, who continue to stage weekly protests against ongoing Israeli land grabs.

Joe Biden has said he opposed Israel's designs for annexation of territory recognized internationally as belonging to Palestinians. A Biden administration would have to navigate carefully, however, in the face of a powerful pro-Israel lobby at home, represented by groups such as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). In his address to the organization in March, he warned that Netanyahu's hardline policies against Palestinians were alienating Jewish-American youth.

The Israeli leader responded with a vitriol that could cast a shadow on relations between the two countries under a Biden administration, and open the door for greater engagement with Palestinians.

But Biden has emphasized a commitment to Israel's security and has endorsed Israel-Arab peace deals with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Sudan, agreements overseen by Trump in a rare convergence of policies. For Palestinians, these pacts have eroded solidarity with their cause among the Arab League, putting pressure on Abbas to negotiate on increasingly difficult terms.

It remains to be seen if and which other Arab countries will normalize ties with Israel in the months after the election and whether the outcome will affect these nations' decision to do so or not, but Biden would enter office dealing with a very different Middle East than that which Trump or Obama faced.

In a document provided to Newsweek, the Palestine Liberation Organization's Negotiation Affairs Department outlined what was expected of the U.S.

"With less than a week before the U.S. Presidential elections, Palestinians and the citizens of many other States will be paying attention to the outcome of the American political campaign and vote," the statement said. "Regardless of the election results, the Palestinian people will expect an American administration in 2021 that recognizes the legitimate national and human rights of the people of Palestine."

By nearly all accounts, this would describe Biden more than it would Trump.

- Tom O'Connor

Russia: Chaos

Russian President Vladimir Putin speeches during the meeting with leaders of parliamentary parties, at the Kremlin, in Moscow, Russia, early March,6,2020. Mikhail Svetlov/Getty

Russian President Vladimir Putin speeches during the meeting with leaders of parliamentary parties, at the Kremlin, in Moscow, Russia, early March,6,2020. Mikhail Svetlov/GettyFor four years, Biden has derided Trump as Vladimir Putin's poodle, needling the president for accepting Russian help during his 2016 campaign and for failing to stand up to his Russian counterpart on the international arena. For four years, Trump countered that he's been tougher on Russia than any other president, and asserted that his approach to Russia is case by case and pragmatic; he doesn't see Russia as an enemy, but neither would he tolerate Putin getting too far out of line.

From Russia's own perspective, both men are right—to an extent. In some international arenas, such as the Middle East, Russia enjoyed considerable latitude. Much more importantly for Putin, there has been little desire in Trump's White House to intervene in what the Kremlin considers to be its own business: Russia's immediate neighborhood and suppression of domestic opposition and dissent. In contrast to Hillary Clinton, seen in Moscow as a crusading liberal interventionist hell-bent on regime change, Trump evinced little interest in what has been going on inside Russia.

At the same time, after four years of Trump, Russia is more than a little worse for wear. Far from being a reliable ally, the Trump White House again and again slapped Russia (and Putin's own inner circle) with punitive sanctions, and lobbied aggressively against a number of Russian projects, most notably the NordStream 2 gas pipeline to Europe. Whether Trump is doing this out of mercantile sef-interest, to push back against domestic allegations of tolerance of Russian meddling, or simply because of a tug of war between Trump and a more Russia-wary diplomatic corps, is no matter: the results are the same, and they are less than inspiring, from Russia's point of view.

Biden, meanwhile, is not seen as much of a favorable alternative. He has publicly committed himself to settling scores with Russia over its interventions in American policies, and his cabinet is seen as far more likely to take interest in domestic Russian affairs, from corruption to crackdown on opposition figures. The same is doubly true about Russia's sphere of influence: with protests against longtime rulers underway in several former Soviet republics, the Kremlin might wake up to American cheerleading—which it perceives as sabotage—among key neighbors, if not in the streets of Moscow itself.

This is one narrative being pushed by the Kremlin. But as Russian political commentator Konstaint von Eggert noted, Kremlin officials briefing about Putin's fear of losing Trump does little to help the incumbent (much as Putin himself complimenting the Democratic party on its affinity with the Communist party of his youth does little to help Biden). In fact, von Eggert told Newsweek, Putin doesn't particularly fear Biden, if only because of his experience with Obama. "I actually think Putin liked the Obama years very much—because Obama was so weak on Russia," von Eggert said. "He'll be looking forward to Part II."

More than anything else, Putin wants to be left alone in his country and in the enormous geopolitical expanse he claims as his sphere of influence. Neither candidate is ideal here, though he does hope that whoever wins will be preoccupied with domestic concerns for the foreseeable future. In the short term, however, no outcome beckons as much as a contested election, throwing American politics into months, if not years of discord and disarray. "Putin will enjoy a contested election outcome," von Eggert said. "This means more chaos in the U.S. and less attention to his antics."

-Dimi Reider

Philippines: Trump

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte shakes hands with US President Donald Trump (R) during the 31st Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in Cultural Center of the Philippines ( NOEL CELIS/AFP/Getty

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte shakes hands with US President Donald Trump (R) during the 31st Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in Cultural Center of the Philippines ( NOEL CELIS/AFP/GettyWhen Donald Trump tested positive for the coronavirus, his counterpart in the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, wished him well and his spokesman described the pair as "close friends."

Duterte needs the U.S. to act as a buffer to Beijing's increased military assertiveness in the South China Sea, which is the key issue for the Filipino government. At the same time, Duterte is less than keen to ratchet up tensions with his much more powerful neighbor.

Duterte's attempts to balance both have culminated in a discernible pivot towards China. But even that pivot was more erratic than decisive, leaving Duterte ample room to get back into Trump's good graces. In February, Duterte announced he would scrap the two-decades' old Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) which set out rules for U.S. soldiers operating in the former colony. He reversed this decision in June following rising tensions in the region and when the investments he hoped for from China in exchange for keeping the U.S. at arm's length failed to materialize.

Camille Emelia, a journalist with the Filipino news outlet Rappler, told Newsweek that Trump's trade war and approach to Beijing "will put the Philippines in a difficult situation because we don't want to anger China, but we also need the U.S. to retain the balance of power in the region and what China is doing in the South China Sea."

Another aspect of the relationship is the Trump administration's tolerance towards abuses carried out by the Duterte government, in particular around its war on drugs. Greg Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative of the DC-based Centre for Strategic and Maritime Studies told Newsweek: "What many Filipinos like about Trump is the perception he is tough on China, and what Duterte likes about Trump is that he doesn't care about human rights."

Duterte's notorious sensitivity to criticism might make Joe Biden a trickier president for him to deal with as he would pressure the Duterte government to uphold human rights and pursue greater democratic reforms to get U.S. economic and military aid. Overall, the Philippine strongman would be keener to see a Trump continuation, than have to reset ties and adjust to new demands from Biden.

- Brendan Cole

Saudi Arabia: Trump

US President Donald Trump and Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (R) arrive for a meeting on "World Economy" at the G20 Summit in Osaka on June 28, 2019. Eliot BLONDET / AFP/Getty

US President Donald Trump and Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (R) arrive for a meeting on "World Economy" at the G20 Summit in Osaka on June 28, 2019. Eliot BLONDET / AFP/GettyThe beginning of the de-facto reign of crown prince Mohammed Bin Salman in Saudi Arabia briefly seemed like a kind of American dream—a dream shared by a certain strand of American diplomacy straddling the Republican and the Democratic parties alike: a young, charismatic ruler firmly in charge of a major American ally in a key geopolitical region was pledging his allegiance to modernization, economic dynamism and even political reform. Unlike other autocrats who've come to be seen as major Trump allies, bin Salman—or MBS, as he is commonly known—was briefly feted and celebrated by Western liberals as well, with credulous profiles of the leader as an enlightened reformer. Saudi Arabia intensified its drive to punch even above its considerable weight, casting itself as a global hub not just for the petroleum industry but for diplomacy, culture and innovation; and as an unabashedly Islamic, but equally unabashedly pro-Western, alternative to the ascendant regional power, Iran.

These days are long gone, MBS's golden halo dimmed by the stream of horrific images and reports from the Kingdom's campaign in Yemen, the suppression of opposition from within the royal family; and most decisively by the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.

MBS survived all this relatively intact and still very much in charge, in no small part thanks to the unstinting support from Donald Trump, almost the only major world leader to express doubts of MBS's involvement in Khashoggi's killing. Riyadh and Washington see very much eye-to-eye on the question of Iran's growing regional influence, guaranteeing a free pass for whatever Saudi might get up to in Yemen—which it sees primarily as an arena for a proxy war with Tehran—and a strong American endorsement for a Sunni-Israel coalition spanning the region. A Biden administration might be more demanding on human rights at home and in Yemen, and would almost certainly favor a rapprochement with Iran, forsaking the coalition that has just begun to take shape, and perhaps not reacting to conventional Iranian military build-up (such as ballistic missiles and air defenses) as forcefully as Riaydh would like.

Still, even a Biden administration would need to remain in Saudi's good graces. Some strings might get attached to some forms of America's support for Riyadh, especially on weapon deals; a polite but firm reminder of MBS's promised reforms might arrive. But MBS has plenty of concessions to trade in exchange for being left alone. Whether Biden plans to confront Tehran or re-engage with it, Saudi cooperation is vital—and that's aside from the importance of Saudi crude oil to the Western energy market, especially if Biden makes good on his plans to make America's domestic energy greener. Of all the autocrats who hitched their cart to the Trump parade, MBS probably has the least to fear from a change of guard.

- Dimi Reider

Syria: Biden

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad gestures during an exclusive interview with AFP in the capital Damascus on February 11, 2016. ( JOSEPH EID/AFP/Getty

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad gestures during an exclusive interview with AFP in the capital Damascus on February 11, 2016. ( JOSEPH EID/AFP/GettyWhile former President Obama may have brought the U.S. into Syria, first through support for insurgents and later through a U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State militant group (ISIS), President Trump inherited the most intensive stretch of the battle and oversaw the tactical defeat of the jihadis.

The strategic shift from regime change to counterterrorism, a favored goal of a U.S. leader purporting to seek an end to the "endless wars" launched by his predecessors, ultimately benefited the Syrian government, which managed to retake most of the country with support from Russia and Iran.

Neither willing to normalize ties with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, against whose government Trump has twice ordered airstrikes in retaliation for alleged chemical weapons attacks, nor to militarily push for his removal, risking a total state collapse and even conflict with his foreign backers, Washington has reached an impasse in the war-torn country.

The military result has been a lingering U.S. military presence of a few hundred troops embedded near oil fields in the northeast and a desert outpost in the south, with no clear way out.

Economically, the outcome has been a series of increasingly crushing sanctions aimed at Assad for his alleged war crimes, which have hampered reconstruction efforts and sent the national currency into a death spiral. The Syrian government has gained ground on the battlefield but finds itself struggling to stay afloat financially, as do its estimated 17 million people.

Signs of potential diplomacy between Washington and Damascus emerged in the weeks leading up to the election, conducted quietly and under the premise of returning two U.S. citizens who disappeared years ago in Syria. Assad's demands include the withdrawal of U.S. troops and lifting of sanctions, as Newsweek recently reported.

So far, little appears to have come of these discussions.

But Assad would not necessarily celebrate a victory for former Vice President Joe Biden, who served the administration that initiated the covert campaign to topple the Syrian leader. The Democratic candidate has expressed no interest in talking with Assad.

At the same time, Biden was also quiet among the more hawkish voices driving Syria policy during the Obama era. He's historically shared some of Trump's skepticism in backing an insurgency against Damascus as well. He's even appeared to share the current administration's support for leaving a small contingent of U.S. troops as a means to pressure Damascus.

Despite these commonalities, there is at least one departure that could decisively affect Syria's interests: Biden's approach towards Iran.

Targeted by unilateral sanctions since Trump's exit from a nuclear deal forged under Obama, the Islamic Republic's ability to financially support its only Arab ally has taken a major hit. Biden has vowed to rejoin the milestone agreement, a development that could see new, much-needed capital flowing into Syria.

And whereas Biden has disagreed with Trump's hardline stance against Iran, the former vice president has criticized his appeasement of Turkey, a NATO ally that has launched its own campaigns against Pentagon-backed Syrian Kurdish forces that played a frontline role against ISIS.

Hopes for a political solution are bogged down in the competing interests of various local, regional and international powers, and Syria sees pro-opposition Turkey as the final obstacle to a de facto military victory in the last opposition-held province of Idlib.

With few good options, a Biden win may bring marginally better results for Syria.

- Tom O'Connor

Taiwan: Trump

The US plane carrying US Health Secretary Alex Azar on board, lands at Sungshan Airport in Taipei on August 9, 2020. CHEN CHUN-YAO/POOL/AFP/Getty

The US plane carrying US Health Secretary Alex Azar on board, lands at Sungshan Airport in Taipei on August 9, 2020. CHEN CHUN-YAO/POOL/AFP/GettyIn December 2016, before voters in the United States even got the chance see how then president-elect Donald Trump would handle the country's long-established foreign policies, the people of Taiwan had already caught a glimpse of his unpredictability when he announced—on Twitter—that he had taken a call from their president, Tsai Ing-wen.

By all accounts, the congratulatory phone call lasted only 10 minutes but it paved the way for a fruitful U.S.–Taiwan relationship which has seen escalating weapons procurement and the highest-level visit by a U.S. Cabinet official in over four decades. The result is that the democratic island is now the only country in the Asia-Pacific to prefer a Trump re-election.

With military pressure in the Taiwan Strait threatening to boil over and the Trump administration on course for a record number of arms sales to Taipei, it is little wonder 53 percent of the Taiwanese public polled said they thought Trump would benefit their nation more, while only 16.4 percent believed his Democratic challenger Biden was up for the task—even if 60 percent polled said they did not trust the American incumbent.