BARBARA DEMICK

In china, history long occupied a quasi-religious status. During imperial times, dating back thousands of years and enduring until the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, historians’ dedication to recording the truth was viewed as a check against wrongdoing by the emperor. Rulers, though forbidden from interfering, of course tried.

So have their successors. Among the most intent on harnessing history for political gain are the current leaders of the Chinese Communist Party. They routinely scrub Chinese-language scholarly books, journals, and textbooks of anything that might undermine their own legitimacy—including anything that tarnishes Mao Zedong, the founding father of the party. The effort, no small task, has not gone unchallenged. A web of amateur historians has been collecting documents and eyewitness testimony from the seven decades that have elapsed since the establishment of modern China in 1949. Guo Jian, an English professor at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater who has translated some of their findings, describes the tenacious researchers as “the inheritors of China’s great legacy,” dedicated to “preserving memory against repression and amnesia.’’

The best-known of the new self-styled historians is Yang Jisheng, whose detailed account of Mao’s Great Leap Forward—the world’s worst man-made disaster, an ill-conceived attempt to jump-start China’s economy that led to the deaths of some 36 million people by famine—was published in Hong Kong in 2008. Though this book, Tombstone, was banned on the mainland, it circulated there in samizdat versions available online and from itinerant booksellers, who hid copies on their pushcarts. Four years later, edited and translated into English by Guo and Stacy Mosher, it was published internationally to great acclaim, and in 2016, Yang received an award for “conscience and integrity in journalism” from Harvard. He was forbidden to leave the country to attend the awards ceremony, and has told friends that he fears he is under constant surveillance.

Rather than being chastened, Yang has done it again. His latest book, The World Turned Upside Down, was published four years ago in Hong Kong and is now in English, thanks to the same translators. It is an unsparing account of the Cultural Revolution, another of Mao’s misadventures, which began in 1966 and ended only with his death in 1976.

yang was born in 1940 in Hubei province, in central China. In a heartbreaking scene in Tombstone, he writes of coming home from school to find his beloved uncle—who had given up his last morsel of meat so that the boy he had raised as a son could eat—unable to lift a hand in greeting, his eyes sunken and his face gaunt. That happened in 1959, at the height of the famine, but it would be decades before Yang understood that his uncle’s death was part of a national tragedy, and that Mao was to blame.

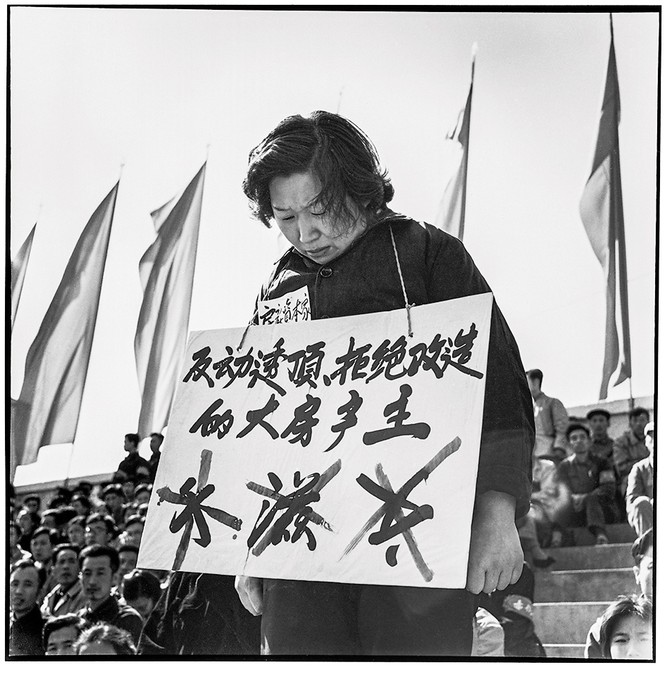

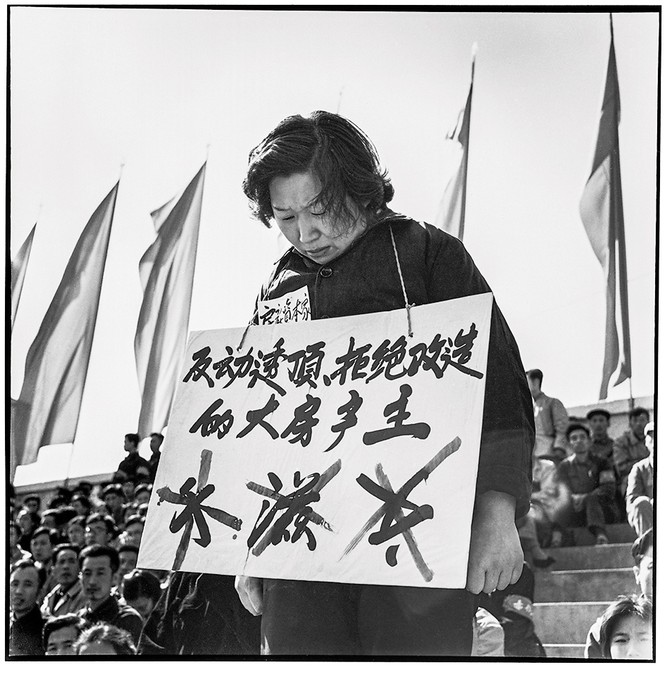

In the meantime, Yang ticked off all the boxes to establish his Communist bona fides. He joined the Communist Youth League; served as editor of his high school’s mimeographed tabloid, Young Communist; and wrote a poem eulogizing the Great Leap Forward. He studied engineering at Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University, although his education was cut short by the start of the Cultural Revolution, when he and other students were sent traveling around the country as part of what Mao called the “great networking” to spread the word. In 1968, Yang became a reporter for Xinhua News Agency. There, he would later write, he learned “how ‘news’ was manufactured, and how news organs served as the mouthpieces of political power.” A property owner is publicly shamed. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

A property owner is publicly shamed. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

A property owner is publicly shamed. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

A property owner is publicly shamed. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)But it wasn’t until the crackdown on prodemocracy demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989 that Yang had a political awakening. “The blood of those young students cleansed my brain of all the lies I had accepted over the previous decades,” he wrote in Tombstone. He vowed to discover the truth. Under the guise of doing economic research, Yang began digging into the Great Leap Forward, uncovering the scale of the famine and the degree to which the Communist Party was culpable. His job at Xinhua and his party membership gave him access to archives closed to other researchers.

In moving on to tackle the Cultural Revolution, he acknowledges that his firsthand experiences during those years did not prove to be much help. At the time, he hadn’t understood it well, and “missed the forest for the trees,” he writes. Five years after the upheaval ended, the Communist Party’s Central Committee adopted a 1981 resolution laying down the official line on the horrifying turmoil. It described the Cultural Revolution as occasioning “the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the state and the people” since the founding of the country. At the same time, it made clear that Mao himself—the inspiration without whom the Chinese Communist Party could not remain in power—was not to be tossed onto the rubbish heap of history. “It is true that he made gross mistakes during the Cultural Revolution,” the resolution continued, “but, if we judge his activities as a whole, his contributions to the Chinese revolution far outweigh his mistakes.” To exonerate Mao, much of the violence was blamed on his wife, Jiang Qing, and three other radicals, who came to be known as the Gang of Four.

In The World Turned Upside Down, Yang still dwells very much amid the trees, but he now brings vividness and immediacy to an account that concurs with the prevailing Western view of the forest: Mao, he argues, bears responsibility for the cascading power struggle that plunged China into chaos, an assessment supported by the work of, among other historians, Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, the authors of the 2006 classic Mao’s Last Revolution. Yang’s book has no heroes, only swarms of combatants engaged in a “repetitive process in which the different sides took turns enjoying the upper hand and losing power, being honored and imprisoned, and purging and being purged”—an inevitable cycle, he believes, in a totalitarian system. Yang, who retired from Xinhua in 2001, didn’t obtain as much archival material for this book, but he benefited from the recent work of other undaunted chroniclers, whom he credits for many chilling new details about how the violence in Beijing spread to the countryside.

the cultural revolution was Mao’s last attempt at creating the utopian socialist society he’d long envisioned, although he may have been motivated less by ideology than by political survival. Mao faced internal criticism for the catastrophe that was the Great Leap Forward. He was unnerved by what had happened in the Soviet Union when Nikita Khrushchev began denouncing Joseph Stalin’s brutality after his death in 1953. China’s aging despot (Mao turned 73 the year the revolution began) couldn’t help but wonder which of his designated successors would similarly betray his legacy.

To purge suspected traitors from the upper echelons, Mao bypassed the Communist Party bureaucracy. He deputized as his warriors students as young as 14 years old, the Red Guards, with caps and baggy uniforms cinched around their skinny waists. In the summer of 1966, they were unleashed to root out counterrevolutionaries and reactionaries (“Sweep away the monsters and demons,” the People’s Daily exhorted), a mandate that amounted to a green light to torment real and imagined enemies. The Red Guards persecuted their teachers. They smashed antiques, burned books, and ransacked private homes. (Pianos and nylon stockings, Yang notes, were among the bourgeois items targeted.) Trying to rein in the overzealous youth, Mao ended up sending some 16 million teenagers and young adults out into rural areas to do hard labor. He also dispatched military units to defuse the expanding violence, but the Cultural Revolution had taken on a life of its own. Schoolchildren march on National Day. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

Schoolchildren march on National Day. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

Schoolchildren march on National Day. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

Schoolchildren march on National Day. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)In Yang’s pages, Mao is a demented emperor, cackling madly at his own handiwork as rival militias—each claiming to be the faithful executors of Mao’s will, all largely pawns in the Beijing power struggle—slaughter one another. “With each surge of setbacks and struggles, ordinary people were churned and pummeled in abject misery,” Yang writes, “while Mao, at a far remove, boldly proclaimed, ‘Look, the world is turning upside down!’ ”

Yet Mao’s appetite for chaos had its limits, as Yang documents in a dramatic chapter about what is known as “the Wuhan incident,” after the city in central China. In July 1967, one faction supported by the commander of the People’s Liberation Army forces in the region clashed with another backed by Cultural Revolution leaders in Beijing. It was a military insurrection that could have pushed China into a full-blown civil war. Mao made a secret trip to oversee a truce, but ended up cowering in a lakeside guesthouse as violence raged nearby. Zhou Enlai, the head of the Chinese government, arranged his evacuation on an air-force jet.

“Which direction are we going?” the pilot asked Mao as he boarded the plane.

“Just take off first,” a panicked Mao replied.

What started as casual brutality—class enemies forced to wear ridiculous dunce caps or stand in stress positions—degenerated into outright sadism. On the outskirts of Beijing, where traffic-crammed ring roads now lead to walled compounds with luxury villas, neighbors tortured and killed one another in the 1960s, using the cruelest methods imaginable. People said to be the offspring of landlords were chopped up with farm implements and beheaded. Male infants were torn apart by the legs to prevent them from growing up to take revenge. In a famous massacre in Dao County, Hunan province, members of two rival factions—the Red Alliance and the Revolutionary Alliance—butchered one another. So many bloated corpses floated down the Xiaoshui River that bodies clogged the dam downstream, creating a red scum on the reservoir’s surface. During a series of massacres in Guangxi province, at least 80,000 people were murdered; in one 1967 incident, the killers ate the livers and flesh of some of their victims.

An estimated 1.5 million people were killed during the Cultural Revolution. The death toll pales in comparison to that of the Great Leap Forward, but in some ways it was worse: When people consumed human flesh during the Cultural Revolution, they were motivated by cruelty, not starvation. Stepping back from the grim details to situate the upheaval in China’s broader history, Yang sees an inexorable dynamic at work. “Anarchism endures because the state machine produces class oppression and bureaucratic privilege,” he writes. “The state machinery is indispensable because people dread the destructive power of anarchism. The process of the Cultural Revolution was one of repeated struggle between anarchism and state power.’’

in china, the Cultural Revolution has not been quite as taboo as other Communist Party calamities, such as the Great Leap Forward and the Tiananmen Square crackdown, which have almost entirely vanished from public discourse. At least two museums in China have collections dedicated to the Cultural Revolution, one near Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, and another in the southeastern port city of Shantou, which now appears to be closed. And for all the horrors associated with that period, many Chinese and foreigners have a fondness for what has since become kitsch—the Mao pins and posters, the Little Red Books that the marauding Red Guards waved, even porcelain figurines of people in dunce caps. (I confess I bought one a few years back at a flea market in Beijing.) A decade ago, a craze for Cultural Revolution songs, dances, and uniforms took off in the huge southwestern city of Chongqing, tapping a vein of nostalgia for the revolutionary spirit of the old days. The campaign was led by the party boss Bo Xilai, who was eventually purged and imprisoned in a power struggle that ended with the ascension of Xi Jinping to the party leadership in 2012. History seemed to be repeating itself.

Although Xi is widely considered the most authoritarian leader since Mao, and is often referred to in the foreign press as “the new Mao,” he is no fan of the Cultural Revolution. As a teenager, he was one of the 16 million Chinese youths exiled to the countryside, where he lived in a cave while toiling away. His father, Xi Zhongxun, a former comrade of Mao’s, was purged repeatedly. And yet Xi has anointed himself the custodian of Mao’s legacy. He has twice paid homage to Mao’s mausoleum in Tiananmen Square, bowing reverently to the statue of the Great Helmsman.

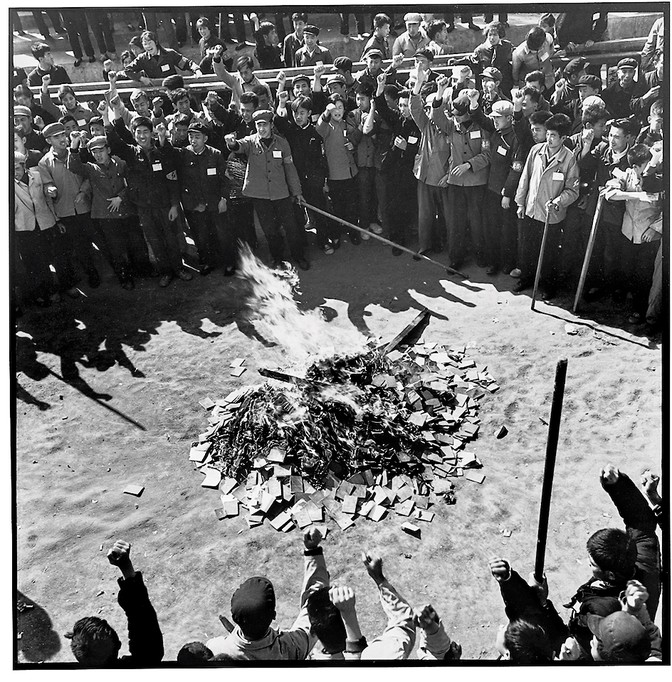

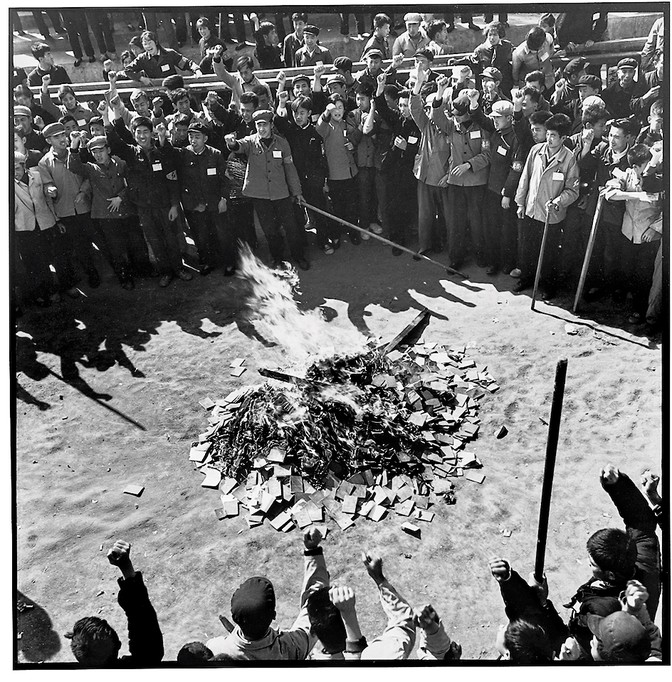

Tolerance for free expression has shrunk under Xi. A few officials have been fired for criticizing Mao. In recent years, teachers have been disciplined for what is called “improper speech,” which encompasses disrespecting Mao’s legacy. Some textbooks gloss over the decade of chaos, a retreat from the admission of mass suffering in the 1981 resolution, which ushered in a period of relative openness compared with today. Confiscated stocks and savings-deposit books are burned. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

Confiscated stocks and savings-deposit books are burned. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

Confiscated stocks and savings-deposit books are burned. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)

Confiscated stocks and savings-deposit books are burned. (Li Zhensheng / Contact Press Images)In 2008, when Tombstone first appeared, the Chinese leadership was more accepting of criticism. Two of Yang’s contemporaries at Tsinghua University in the 1960s had by then risen to the top ranks of the Communist Party—the former leader Hu Jintao and Wu Bangguo, the head of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress—and he received indirect messages of support, according to Minxin Pei, a political scientist at Claremont McKenna College and a friend of Yang’s. “The book resonated with the top Chinese leadership because they knew the system could not produce its own history,” he told me. The problem for Yang today “is the overall sense of insecurity of the current regime.”

Yang, now 81, is still living in Beijing. He was so nervous about the repercussions of The World Turned Upside Down that he initially tried to delay publication of the English edition, according to friends, out of worry that his grandson—who was applying to university—might bear the brunt of reprisals. But the repressive political climate in China today makes honest assessments of Communist Party history ever more urgent, Guo told me. “Ever since the time of Zuo Qiuming [a historian from the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.] and Confucius, truthfully recorded history has been considered a mirror against which the present is viewed and a stern warning against rulers’ abuse of power.” He pointed as well to a more contemporary, Western source, George Orwell’s 1984, and its mantra, “Who controls the past controls the future: Who controls the present controls the past.”

Unlike the imperial dynasties, the Communist Party can’t claim a mandate from heaven. “If it admits error,” Guo said, “it loses legitimacy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment