GORDON G. CHANG

Aspat between McKinsey & Company, the world's largest consulting firm, and Senator Marco Rubio, the Florida Republican, highlights a critical American national security vulnerability to China.

The consultancy has been caught covering up its work for the "Chinese government." McKinsey denies deception, but the episode suggests it knows its dual representation of the American and Chinese governments does not serve U.S. interests.

"It has come to my attention that McKinsey & Company appears to have lied to me and my staff on multiple occasions regarding McKinsey's relationship with the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese government," Rubio wrote in a December 16 letter to Bob Sternfels, McKinsey's global management partner, in San Francisco.

Rubio contends that in July 2020, the firm told him that neither the Chinese government nor the Chinese Communist Party was ever a McKinsey client. The senator also reported that McKinsey repeated its assertion to his advisors in a March 2021 Zoom conference call. Yet in a September 2020 court filing relating to Valaris, an offshore drilling company, McKinsey disclosed its work for the "Chinese government."

McKinsey says its disclosure in the Valaris case "reflects an accurate description of client service that includes local and provincial government, and is entirely consistent with the type of work we communicated openly about with the senator's office."

The firm also stated this, again in reference to its Valaris disclosure: "In no way does it refer to work for the Central Government, Communist Party of China or the Central Military Commission of China, none of which are clients of McKinsey, and to our knowledge, have never been clients of McKinsey."

McKinsey is attempting to minimize the significance of its work in China by making highly technical arguments about the nature of Chinese governance. The consultancy is correct, as a technical matter, that the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party are not, as Rubio argues, one and the same.

In the Maoist era, there was no meaningful distinction between the Party and the government. In the succeeding "reform era," there were substantial efforts to separate the two, but during the rule of Xi Jinping, now in power, the Party has blurred the line again. The distinction is not as distinct as it once was.

McKinsey is also trying to draw a distinction between the Chinese central government and lower-tier governments. China, however, has a unitary government. There is no concept of divided sovereignty, such as that which exists in the United States and other countries with federal systems. There is one "Chinese government," and it is under the firm control of the Chinese Communist Party.

In any event, the precise characterization of McKinsey's clients is of no relevance for the critical issue at hand: Does the firm's work for both Chinese and American clients pose a risk for U.S. national security?

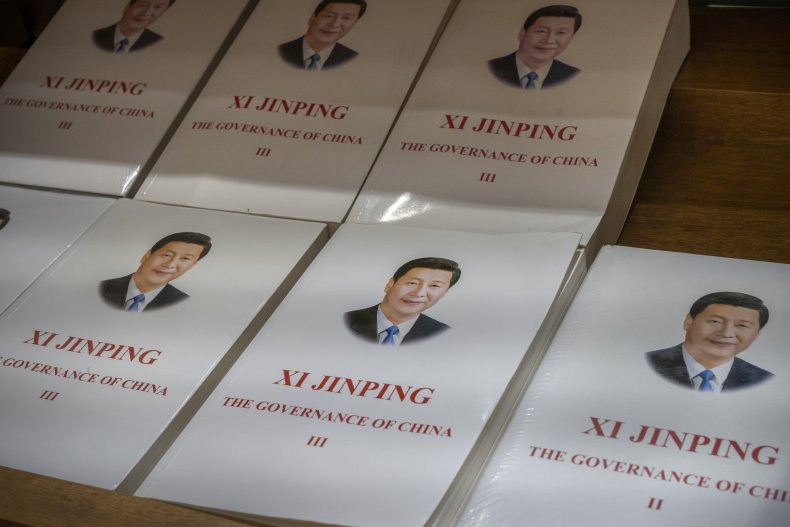

Xi Jinping's "The Governance of China III" books, translated in English, are seen on sale in a bookstore on December 15, 2021 in Beijing, China. The book is part of a three-volume collection containing speeches and writings by Chinese President Xi Jinping.ANDREA VERDELLI/GETTY IMAGES

Xi Jinping's "The Governance of China III" books, translated in English, are seen on sale in a bookstore on December 15, 2021 in Beijing, China. The book is part of a three-volume collection containing speeches and writings by Chinese President Xi Jinping.ANDREA VERDELLI/GETTY IMAGESRubio has a clear answer. "These previously undisclosed relationships between McKinsey & Company and the CCP, the Chinese government and CCP-related entities pose serious institutional conflicts of interest," he wrote in his December 16 letter to the firm. "It is increasingly clear that McKinsey & Company cannot be trusted to continue working on behalf of the United States government, including our intelligence community."

The Florida senator is correct on the nature and extent of the risk. China is now in a position to use lucrative consulting arrangements with McKinsey to obtain information about American businesses and the U.S. intelligence community.

The consultancy has worked for the CIA, FBI, NSA and DOD. At the same time, the firm represents, or has represented, 22 of the 100 largest Chinese state-owned enterprises and nine of the top 20 Belt & Road Initiative contractors.

That revenue stream obviously gives Beijing influence over McKinsey.

"McKinsey represents a treasure trove of valuable intelligence for the Chinese security services," Roger Robinson, former chairman of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, told the Daily Caller last year. "Such services—and the state-controlled enterprises that do their bidding—live to access forensic assessments of the internal operations of key American companies, and even government agencies."

As Robinson pointed out, "After a big dinner with wine, someone from the Chinese side will say, 'We know you can't say much, but could you give us some insights?'"

Moreover, McKinsey partners and staff may be under a legal compulsion to spy. In the Chinese Communist Party's top-down system, obedience to its directives is mandatory. Furthermore, Articles 7 and 14 of China's 2017 National Intelligence Law affirmatively require every Chinese national to commit espionage if a demand is made.

We do not know whether Beijing has in fact tried to use McKinsey for this purpose, but the potential for great harm exists nonetheless. Because China has such leverage over McKinsey, Washington should make the consultancy choose: work for America or work for China, but not both.

The recent Rubio-McKinsey dust-up shows that the consulting firm is engaging in "apparent doublespeak, conflicts of interest and back-pedaling on its China contracts, including those with the Chinese regime," Anders Corr, the publisher of The Journal of Political Risk, tells Newsweek. That deception suggests McKinsey knows that Rubio is correct on the implications of its dual representation.

Corr, also the author of the just-released The Concentration of Power: Institutionalization, Hierarchy & Hegemony, believes the U.S. must now take action. "Unscrupulous companies that do business with corporations and government entities in China should feel the full weight of the law, including new tougher legislation and prosecution of any past criminality," he told this publication.

Yes, America needs tougher laws. In the meantime, President Biden can invoke the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 to force McKinsey to make a choice.

No comments:

Post a Comment