Jessica Brandt and Valerie Wirtschafter

Users come to search engines seeking honest answers to their queries. On a wide range of issues—from personal health, to finance, to news—search engines are often the first stop for those looking to get information online. But as authoritarian states like China increasingly use online platforms to disseminate narratives aimed at weakening their democratic competitors, these search engines represent a crucial battleground in their information war with rivals. For Beijing, search engines represent a key—and underappreciated vector—to spread propaganda to audiences around the world.

On a range of topics of geopolitical importance, Beijing has exploited search engine results to disseminate state-backed media that amplify the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda. As we demonstrate in our recent report, published by the Brookings Institution in collaboration with the German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy, users turning to search engines for information on Xinjiang, the site of the CCP’s egregious human rights abuses of the region’s Uyghur minority, or the origins of the coronavirus pandemic are surprisingly likely to encounter articles on these topics published by Chinese state-media outlets. By prominently surfacing this type of content, search engines may play a key role in Beijing’s effort to shape external perceptions, which makes it crucial that platforms—along with authoritative outlets that syndicate state-backed content without clear labeling—do more to address their role in spreading these narratives.

Using search to shape views of Xinjiang and COVID-19

To evaluate the prevalence of Chinese state media across search results, we first developed a list of 12 key terms related to Xinjiang and COVID-19 and then tracked the extent to which these terms returned search results from Chinese state media. Over the course of four months, we then collected the first page of (or first ten) search results for each of these terms from Google News, Bing News, Google Search, Bing Search, and YouTube every day between November 1, 2021, and February 28, 2022. We then classified the results from each day based on whether they returned known state-backed media sources.

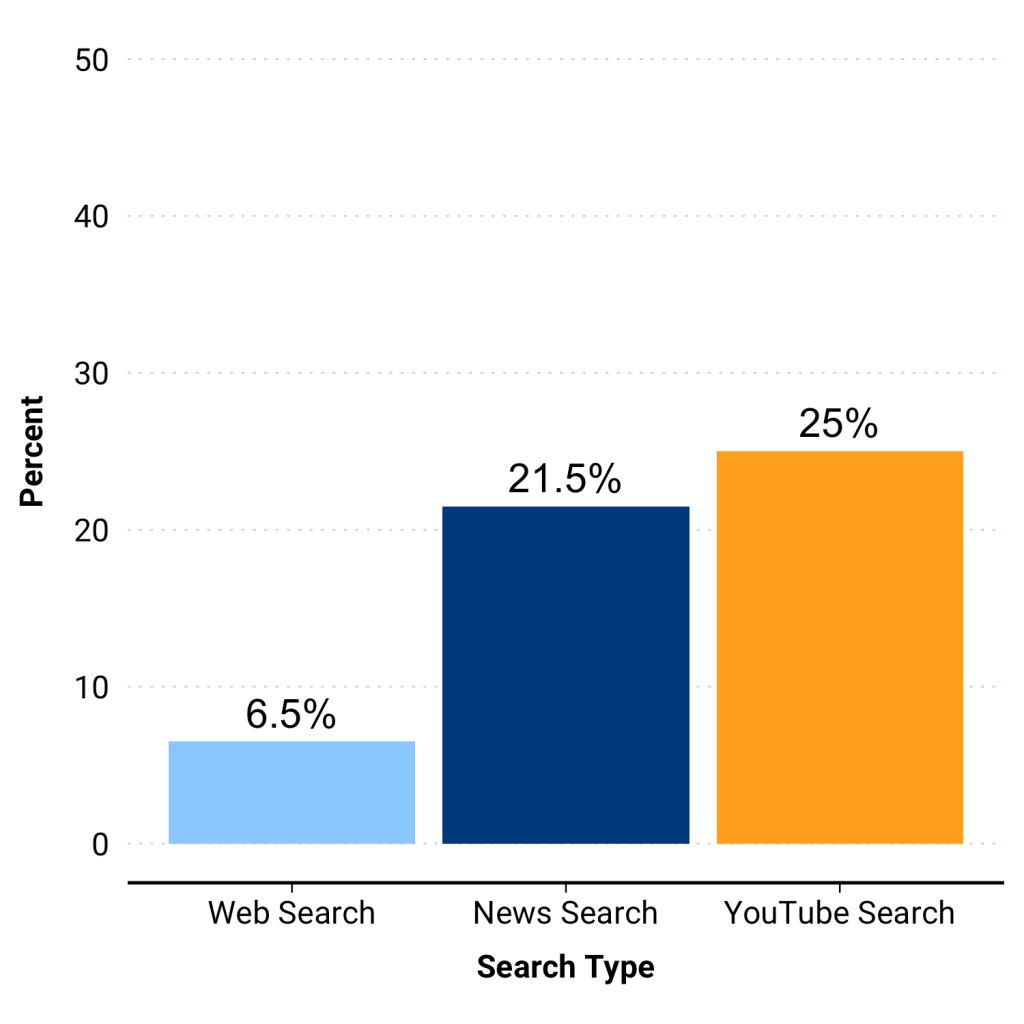

During the 120 days that we tracked search engine results for terms linked to Xinjiang and COVID-19, Chinese state media featured prominently. Some 21.5% of the top results on Google News and Bing News returned Chinese state-backed media, and one quarter of top results on YouTube featured state-backed accounts. For web searches, 6.5% of top results featured state media. For users looking to educate themselves on events in Xinjiang or about COVID-19, this meant that it was likely that at least some of the information they consumed would come from Chinese state media.

Figure 1: YouTube and news searches returned a high volume of Chinese state media in top search results

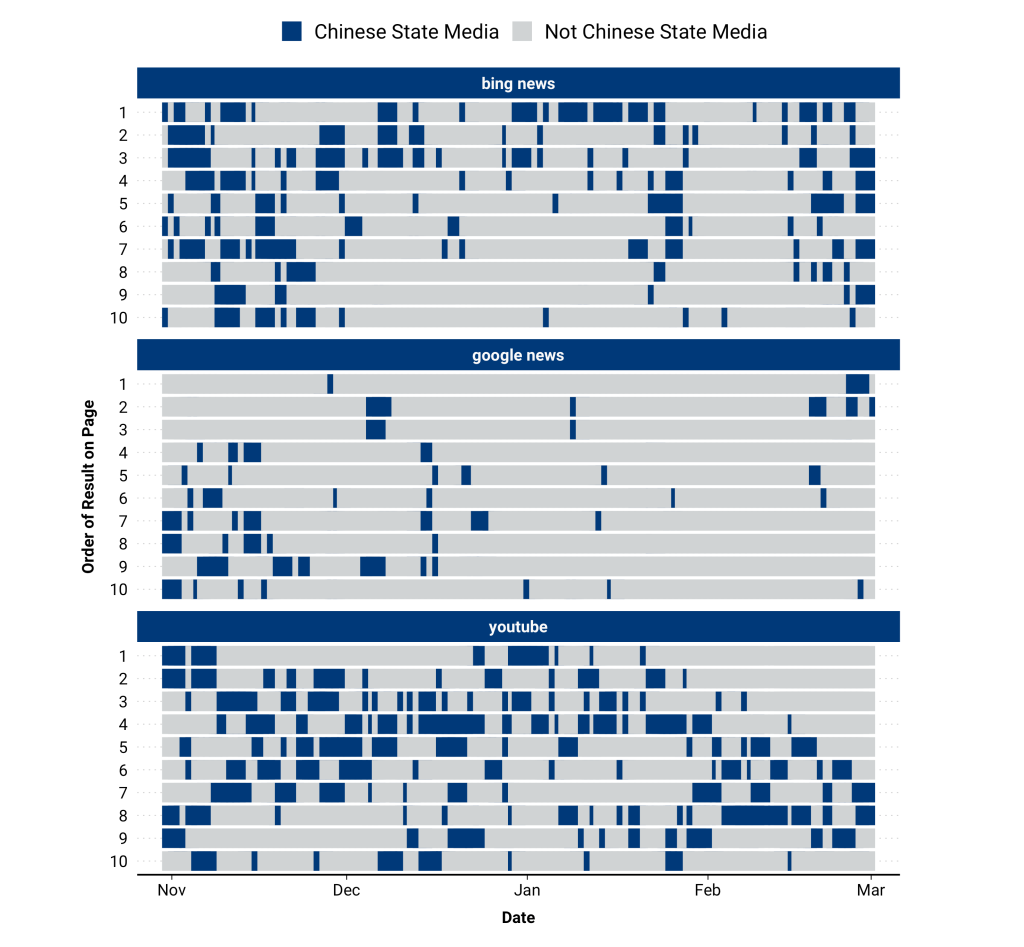

It would be reasonable to assume that choosing benign, neutral terms for a search query would return factual content, but even for neutral and widely used terms, we found Chinese state media performing well in search results. For searches related to Xinjiang, for example, we found that Beijing was remarkably effective at influencing the content that surfaces for the neutral and widely used term “Xinjiang.” Over the 120-day period, the term returned Chinese-state media in top results in 88% of News searches and 98% of YouTube searches (Figure 2). These results demonstrate how easy it is for users to stumble across state-backed content even when conducting a seemingly neutral search.

Figure 2: Chinese state media featured prominently in top news and YouTube searches for the neutral term “Xinjiang”

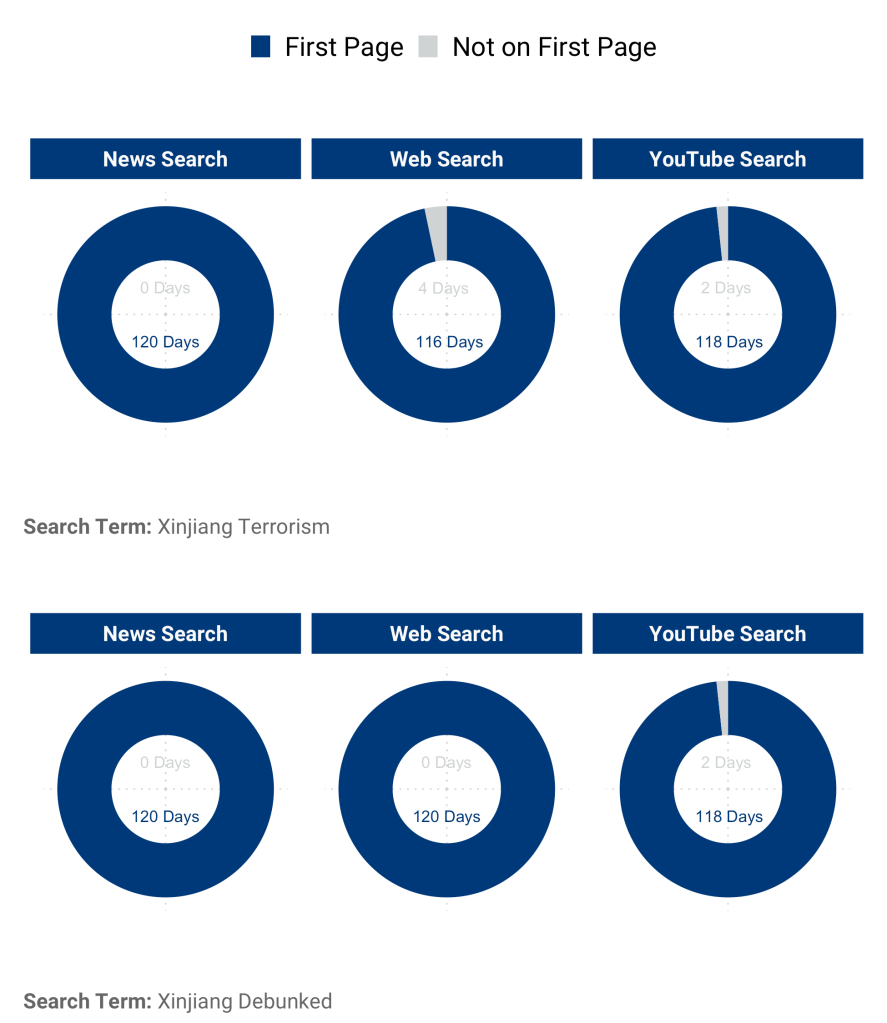

Less surprisingly, search results for conspiratorial terms yielded a high volume of state-driven content. Terms like “Xinjiang debunked” and “Xinjiang terrorism” returned at least one result on the first page from Chinese state media across web, news, and YouTube searches nearly every day (Figure 3). On average, more than half of all search results for the term “Xinjiang debunked” and one third of all search results for the term “Xinjiang terrorism” originated from Chinese-state media each day. In each of these cases, search results were dominated by state-backed propaganda that regularly supplied content referencing these loaded search terms.

Figure 3: State-backed content dominated top search results for conspiratorial terms like “Xinjiang Debunked” and “Xinjiang Terrorism”

More than two years after the outbreak of COVID-19, the origin of the virus remains a topic of intense interest to Chinese state-backed media, and its content on the issue surfaces regularly on search engines. On YouTube, searches for the term “Fort Detrick,” a U.S. military research lab that CCP propaganda has claimed was the origin of the COVID-19 virus, regularly returned state-backed content. In total, 619 videos from Chinese state media appeared in top 10 results during our study, or around five per day. Similarly, Chinese state media appeared on the first page of search results for news searches for the term “Unit 731”—a biological research unit located in Japan-occupied China during WWII and a subplot in China’s efforts to connect origins of COVID-19 to Fort Detrick—every single day of data collection. Here, what is notable is an information loop. Users might be exposed to state narratives via other mediums—for example, tweets by Beijing’s so-called “Wolf Warrior” diplomats about Unit 731—search to investigate these claims, and find evidence from state-backed media to confirm these conspiratorial claims.

But in seeking to cast doubt on the origin of COVID-19, Chinese state-backed outlets are far less successful in spreading this message via search engines compared to their content about Xinjiang. Chinese-state media surfaced in the top search results for terms tied to Xinjiang almost four times as much as it did for terms tied to COVID-19. This is likely due to the fact that platforms have adopted more stringent policies around the promotion of authoritative content related to COVID-19, the volume of which likely exceeds authoritative content related to events in Xinjiang.

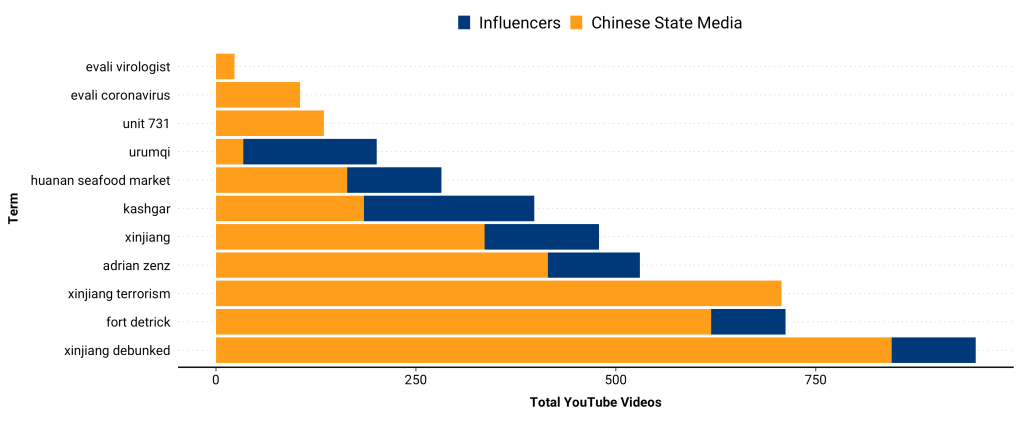

Assessing the data

Given the prevalence of non-transparent content hosting and influencer agreements, the data presented here is an undercount of how widely Chinese state-media appears online. Using exact text matching between search engine results and state media headlines, we found that at least 19 sources without official Chinese-state media affiliation reposted state-backed content verbatim. If these observations were included in our analysis, they would increase the prevalence of Chinese-state media in top search results by nearly 10%. On YouTube, accounting for known Beijing-backed influencers identified by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute would increase the reach of Chinese state media in top search results by at least 27% (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Accounting for known Beijing-backed influencers increases the reach of Chinese state media on YouTube by more 27%

Toward a better search

Users consistently report high trust in search engine results, and this makes it crucial that search engines surface high-quality information. Amid a crisis of online misinformation, users have been encouraged to approach online information skeptically and often turn to search engines to adjudicate competing claims around hot-button issues, believing that they are in control of what they find. The communities organized around viral conspiracy theories—for whom the origin of COVID-19 is a perennial question—understand this dynamic and exhort their members to “do their own research,” understanding that the information they will find will lead them down the rabbit hole of a given conspiracy theory. As our data show, state-media content with little concern for objective fact makes up an important part of the news and YouTube search results for contested terms. These search results can present a distorted perspective to audiences around the world, even for terms as neutral as “Xinjiang.” This makes auditing the prominence of state-backed propaganda across search types particularly important.

Tech companies, content creators, and authoritative media outlets all have a role to play in improving the quality search results. Search platforms could consider expanding practices designed to give users more information about search results, including clear labels for state domains. To address the potential for more conspiratorial terms to yield a high percentage of state-backed propaganda, search engines could expand the use of warning labels to situations where the quality of results may be lacking, including for example, when a small number of sources dominate search results. Finally, to address challenges inherent to hosting, reposting, and syndication of state-backed media, publications that partake in these practices should at minimum enhance disclosures and labels to better inform audiences about the sources of this syndicated information. Authoritative outlets should also reconsider arrangements with state-backed media outlets lacking editorial independence.

Companies are beginning to address the prevalence of state-media content in search results. Last week, Microsoft said that it would consider attaching labels to state sponsored content and that it would produce its first transparency report on efforts to slow the spread of state-backed disinformation later this year. In February, the company announced it would tweak Bing to “only return RT and Sputnik links when a user clearly intends to navigate to those pages.” Google-owned YouTube began labeling state-affiliated accounts in 2018, including Chinese outlets. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Google demonetized and further deranked Russian state media. Curbing the prevalence of state-media in search results requires a difficult weighing of competing interests: Preventing Chinese state media from appearing in search results entirely would impede users from accessing an important, if flawed tool in understanding Chinese society; letting Chinese state-media dominate search results risks exposing users to large quantities of low-quality information.

But in our view, more can be done to improve the quality of search results and minimize the way in which state propagandists exploit search engines to spread their messages. In our report, we detail several additional recommendations designed to limit the unintended reach of state-backed propaganda in search engines. Broadly speaking, these recommendations may help to improve search quality around contested topics or in times of crisis and make it more challenging for Beijing—and other authoritarian governments—to utilize its information apparatus to dominate top search results for geopolitically strategic topics and terms.

No comments:

Post a Comment