On October 16, 2022, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will convene its 20th National Congress to reshuffle the country’s leadership roster and set the political and policy direction going forward. Party congresses, which only take place once every five years, are closely scrutinized for clues into China’s opaque political system. As part of broader personnel shifts, the top brass of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is slated to be significantly altered. This ChinaPower feature analyzes past personnel changes within the PLA leadership to identify important trends and to forecast changes that could take place at the 20th Party Congress. Following the conclusion of the 20th Party Congress, this page will be updated with new information and analysis.

The 20th Party Congress: A Pivotal Moment

The 20th Party Congress comes at a pivotal and challenging moment for China. A severe housing market slump, sluggish global growth, record high youth unemployment, and burdensome “Zero Covid” policies are weighing heavily on the Chinese economy and domestic politics. Beijing also faces a more difficult external security environment and growing challenges abroad. CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping’s more assertive foreign policy has provoked a backlash from the United States and many of its allies and partners. China’s unprecedented military activities around Taiwan in August 2022, coupled with its continued alignment with Russia, have further frayed Beijing’s relations with many countries and raised the risk of regional tensions.

Despite these challenges, there is little evidence that China will change its assertive approach to foreign policy under Xi, who is all but certain to be re-appointed to a third five-year term as China’s leader at the 20th Party Congress. Xi has had two five-year terms as China’s leader to put in place his vision for realizing what he calls the “China Dream” of national rejuvenation. He has secured a strong grip over foreign policy through major hallmarks including the Belt and Road Initiative, the Global Development Initiative, and the Global Security Initiative. He also launched drastic reforms to the PLA in late 2015 and reset modernization goals for the Chinese military up to 2050. With so many efforts already in place, it is likely that the 20th Party Congress will reaffirm Xi’s prior foreign policy decisions and call for continuing his overall approach moving forward.

Yet this is only part of the picture. Even if China’s broad foreign policy and military contours are already in motion, modifications could still have a significant impact on Chinese external behavior. Will Xi, for instance, accelerate certain initiatives—such as outreach to the Global South and formation of closer strategic partnerships with select countries—given the challenges Beijing faces? Will Beijing significantly boost military modernization and readiness given the growing risk of tensions over Taiwan?

China will need experienced leaders to navigate these foreign policy challenges, and the 20th Party Congress will prove pivotal in determining whose hands are on the levers of power. On the last day of the 20th Party Congress, the CCP will announce the composition of its new Central Committee, which comprises roughly 200 of the country’s top officials spanning party, state, and military positions. Immediately after the Party Congress concludes, roughly 25 of these will be chosen to sit on the Central Committee’s Politburo, and from among this a select few will secure a spot on the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee. Similarly, six or so military leaders will be tapped to join the Central Military Commission, which oversees the PLA. These and other personnel shifts during and after the Party Congress will unveil China’s new leadership.

Xi Jinping is likely to have significant influence over the selection of personnel for many of these key positions. Through his anti-corruption campaign and sweeping purges, Xi has largely sidelined the old political factions within the party that previously jockeyed for influence. He has also abolished term limits for the presidency and weakened norms around retirement ages for party officials. He may further erode party norms by pushing to keep key allies in power beyond the established retirement age of 68.1

Given Xi’s influence, a key question for the 20th Party Congress is whether Xi and the party will select officials based on experience and talent or loyalty to Xi. A capable and experienced cohort of top cadres will help China weather mounting challenges at home and abroad. If Xi instead prioritizes loyalty over experience, he may find himself increasingly surrounded by advisers who are unwilling to speak truth to power and unable to stop China from stumbling down faulty and potentially dangerous paths.

The Central Military Commission

Among the crucial decisions to be made at the party congress are appointments to the Central Military Commission (CMC). The CMC sits at the helm of the PLA and controls China’s domestic security forces, the People’s Armed Police. It is responsible for overseeing Beijing’s use of military or security forces to advance its national security and foreign policy objectives. Several members of the CMC also sit on leading party organizations such as the National Security Commission and the Foreign Affairs Commission that determine and set China’s national security and external policies.

The CMC is first and foremost a party organization, meaning China’s military reports to the CCP, not the Chinese state. The CCP prioritizes absolute control over the PLA—a reflection of the famous quote by Mao Zedong that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Control over the PLA is so important that former top party leaders Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin chose to retain their Chairmanship of the CMC even after relinquishing other top state and party titles.

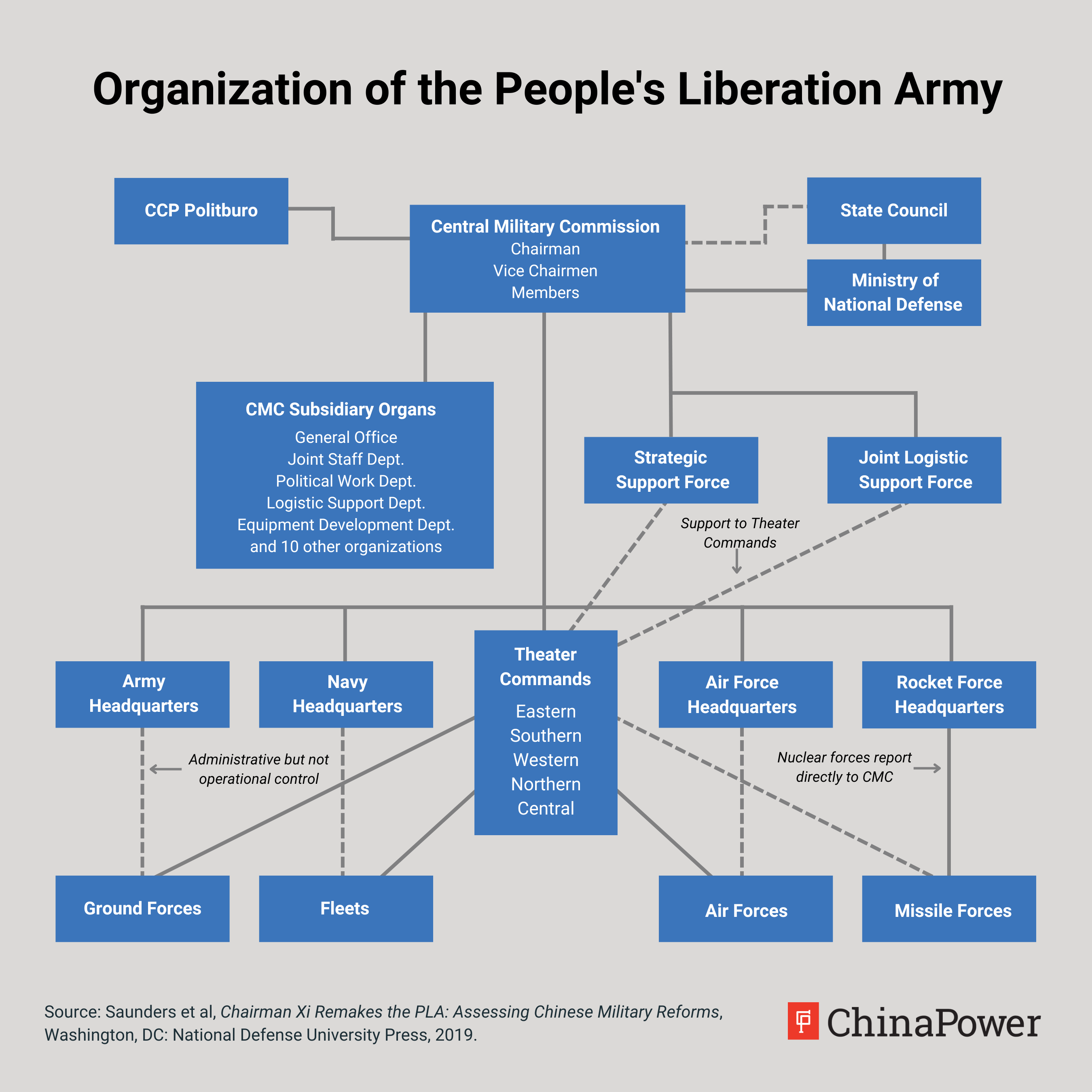

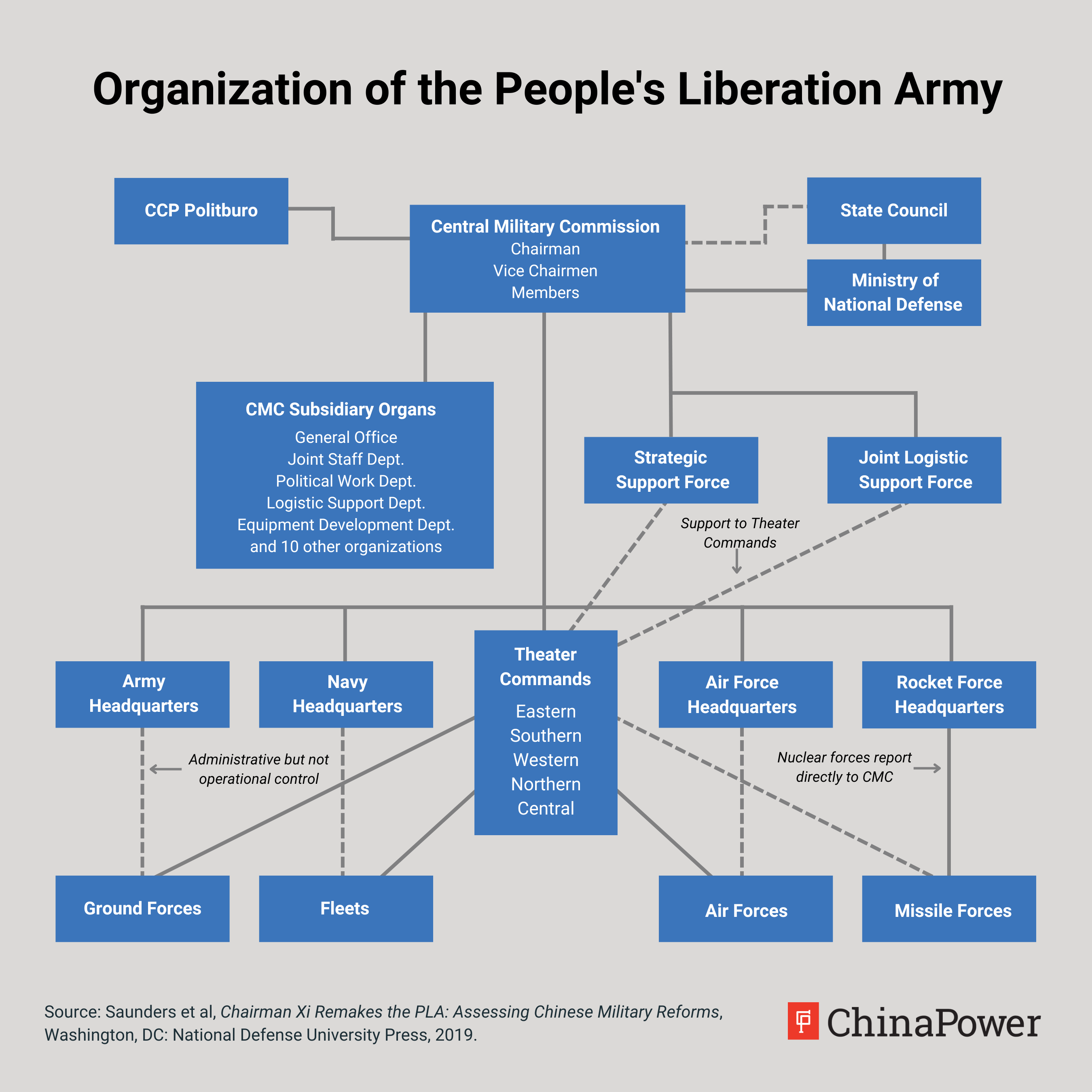

In commanding the PLA, the CMC directs a vast bureaucracy. It oversees the headquarters of the main services—the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force—as well as the Strategic Support Force and Joint Logistic Support Force, which were set up as part of Xi Jinping’s 2016 military reforms. The CMC also directs five theater commands (previously seven military regions), which are in charge of operations within their designated areas. Finally, the CMC oversees a suite of subsidiary departments, offices, and other organizations, such as the Joint Staff Department and the Political Work Department.

Click to enlarge.

Xi Jinping became CCP General Secretary and Chairman of the CMC in late 2012, even before he became China’s president in 2013. He is all but guaranteed to remain Chairman after the 20th Party Congress. Below Xi on the CMC are two Vice Chairmen, both of whom sit on the powerful CCP Politburo. The senior Vice Chairman, General Xu Qiliang, rose through the ranks of the PLA Air Force to become its commander before joining the CMC in 2007 and being promoted to Vice Chairman in 2012. General Zhang Youxia hails from the PLA Army and served as Commander of the Shenyang Military Region before being promoted to the CMC in 2012 and becoming its Vice Chairman in 2017.

Rounding out the current CMC are four regular members: General Wei Fenghe, General Li Zuocheng, Admiral Miao Hua, and General Zhang Shengmin. Each of these four members have seats on the CCP Central Committee and concurrently hold important positions within the PLA. General Wei is a State Councilor and Minister of Defense, and General Li is Chief of the CMC Joint Staff Department, which oversees operational planning and command. Admiral Miao is head of the CMC Political Work Department, which directs all party and cultural work within the PLA, and General Zhang is head of the CMC Discipline Inspection Commission, which oversees anti-corruption investigations.

China’s Central Military Commission

Scroll to view all members. Use the toggle buttons below to filter by position.

Trends in CMC Personnel Changes

The analysis in this section is derived from a biographical database of CMC members compiled by the ChinaPower team. The database is available here.

The CCP leadership has wide discretion over the membership of the CMC. Neither the party nor the state constitutions outline the selection process for the CMC. Events of recent years indicate that Xi has attained substantial influence over the PLA, including the makeup of the CMC. Toward the end of his first term, in late 2015 and early 2016, Xi initiated sweeping reforms of the PLA’s structure which had direct impacts on the CMC and the bureaucracy it oversees. Xi’s influence over the CMC has likely grown with time. Having consolidated considerable political influence during his first term, he was better poised to impose his preferences on CMC appointments during his second term and thereafter.

One of the most notable features of the CMC in recent years is the absence of a civilian senior Vice Chairman position, which was typically filled by China’s leader-in-waiting in the years just before his promotion into the top leadership role. Xi Jinping was CMC Vice Chairman from 2010 to 2012 immediately prior to becoming China’s paramount leader. Hu Jintao was likewise CMC Vice Chairman from 1999 to 2004 before (and after) becoming party and state leader.2

Under Xi’s leadership, however, no civilian has been named a CMC Vice Chairman. This could suggest the CCP has not tapped a successor to Xi—or, if they have, the party does not want that successor to be known. It also means that Xi Jinping has less diluted influence over the PLA since, unlike his predecessors, he does not have to contend with a successor on the CMC. It is possible a successor to Xi could be appointed as a CMC Vice Chairman during Xi’s third term (2022–2027), but if precedent holds this would happen near the end of his third term, not during the 20th Party Congress that kicks off Xi’s next five years.

The CMC is not just missing a civilian Vice Chairman; the number of military members has also shrunk. In the preceding two decades, the CMC typically included 9 or 10 military members. These members typically spanned a wide range of positions, including heads of several CMC subsidiary organizations and service commanders. By comparison, the current CMC has only 6 military members, with four of these holding a concurrent position as head of a CMC subsidiary organ. As a result, fewer CMC organizations are represented compared to before, and there are no service commanders on the CMC.

The CMC of Xi’s second term also no longer disproportionately comprises members from the Army. Whereas the CMC of the 15th CCP Central Committee (1997–2002) was entirely made up of members from the Army, the current CMC includes members from each of the four main services, with only two of the six military members coming from the Army. This tracks with a broader effort by Xi Jinping to shift the PLA away from a military dominated by ground forces toward a more joint force with significant air and naval capabilities. As part of this process, Xi announced in 2015 that the PLA would shed some 300,000 personnel, primarily from the Army.

Some of the current CMC members have even served in multiple services, which at face value suggests a more joint-qualified leadership. Admiral Miao Hua spent much of his career in the Army before transitioning to the Navy in 2014. Similarly, General Zhang Shengmin was previously in the Army before transitioning to the Rocket Force. However, both are political track officers who respectively rose through the political commissar system and through the PLA discipline inspection system. Their move from the Army to other services is therefore not an indicator of significant joint experience in terms of operational command. Indeed, the CMC lacks any members with operational experience in the Navy—a situation that could change after the 20th Party Congress.

Furthermore, trends below the CMC level show that the Army is still represented in far greater numbers than other services. The PLA also still lacks high-ranking officers with significant joint experience of the kind that is typical in more joint forces like the U.S. military.

While the current CMC’s membership does not suggest a sprint toward greater jointness across the services, it does show that most of its members have somewhat more diverse experiences than in the past. CMC members are promoted to the CMC only after having served in a theater commander grade (正战区职) position—the highest grade below the grade of CMC member.3 This typically includes being a commander or political commissar of a PLA organization that fits into one of three categories: the services, the theater commands (previously military regions), or a subsidiary organization of the CMC.

In the past, CMC members would typically be promoted to the CMC after having experience in just one of these three categories at the theater commander grade. Under Xi, however, the promotion tracks have become more varied. Among the current CMC, four of the six members served in two areas immediately prior to joining the CMC. For example, General Li Zuocheng served as commander of the Chengdu Military Region and then commander of the PLA Army before being promoted to the CMC. Similarly, Admiral Miao Hua was political commissar of the Lanzhou Military Region and then political commissar of the Navy before joining the CMC.

This change is not necessarily transformative but may suggest that the Chinese leadership is pushing for top PLA officers to have more significant experience serving at high levels across the military bureaucracy. It also has the added benefit of potentially helping to deter corruption, since moving around reduces the ability of officers to establish a “fiefdom” in which they can dominate.

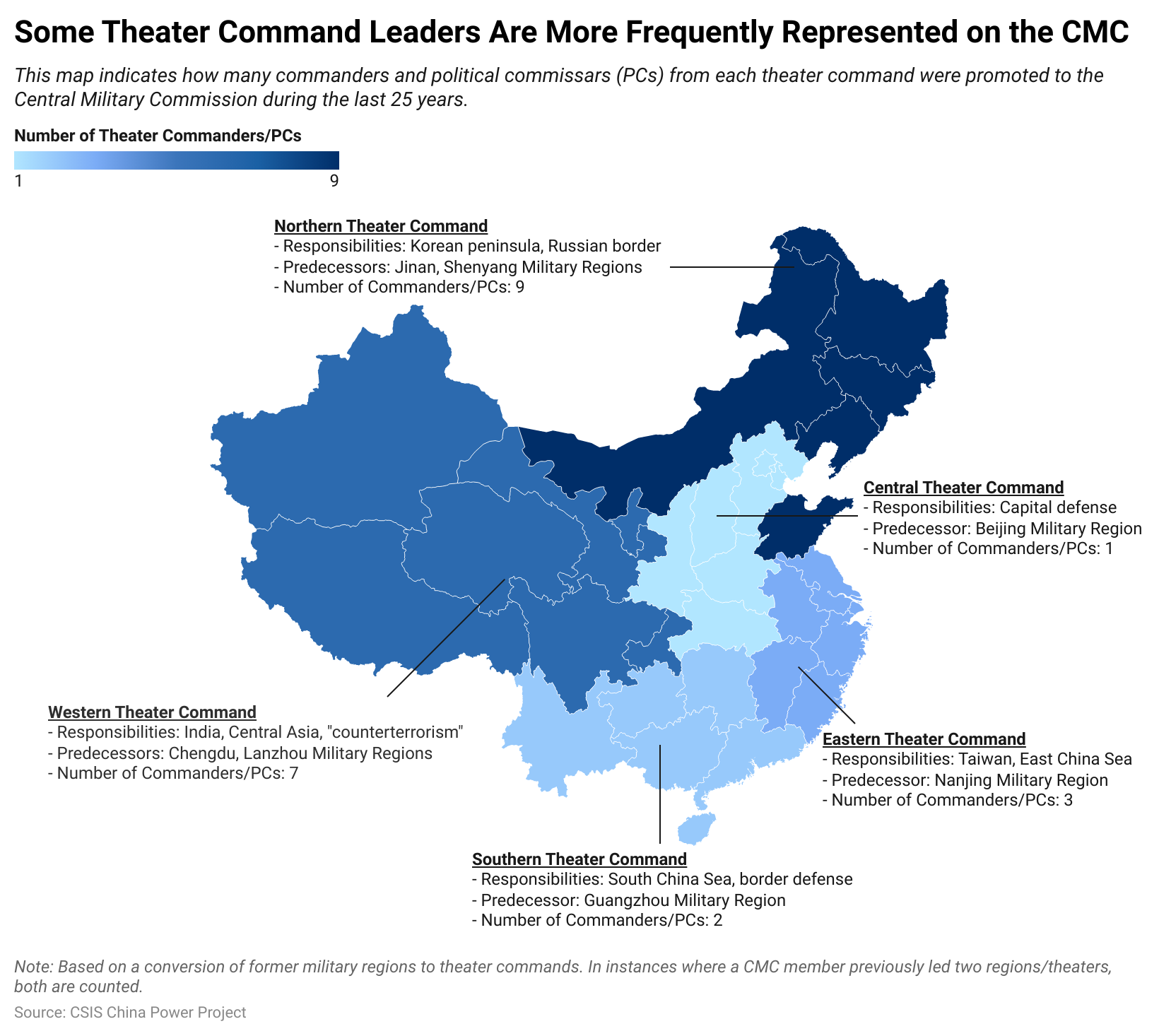

It is worth noting that, among those CMC members of the last 25 years who previously led theater commands—either as commander or political commissar—some theater commands are more represented than others. Nine CMC members came from the Northern Theater Command (including its Shenyang and Jinan Military Region predecessors).4 This is partly because the two regions were merged to create the new theater commands; however, its constituent military regions were themselves the most frequently represented. This is not all that surprising since the Northern Theater Command is responsible for responding to crises and conflicts on the Korean Peninsula, a major potential geopolitical flashpoint.

What is somewhat surprising is that the Eastern and Southern Theater Commands are not more highly represented. The Eastern Theater Command is responsible for Taiwan and the East China Sea—critical and sensitive areas—yet only three of its leaders have made it to the CMC over the past 25 years. Given growing tensions around Taiwan, it is possible that more leaders of the Eastern Theater Command could make their way onto the CMC in the coming years. Similarly, the Southern Theater Command has only sent two leaders to the CMC despite the South China Sea’s importance for Beijing. It too could see greater representation on the CMC going forward.

Click to enlarge.

Three things have largely remained unchanged for CMC members. First, thanks to laws governing PLA promotion and retirement, there has not been a notable shift in the age of CMC members in recent decades. Over the past 25 years, CMC members have joined the commission at an average age of about 60, with the youngest joining at the age of 56 and the oldest joining at 65. CMC Vice Chairmen tend to join at slightly younger ages, which reflects the fact that they typically have longer tenures on the CMC, serving as members before becoming Vice Chairmen.

Second, most CMC members continue to rise to the CMC having served in operational roles rather than political positions. Proportionally, the current CMC contains more political track officers than in the past, but this is due to the shrinking of the CMC rather than an outright increase in the number of political-track members.

Third, the CMC continues to include members who have fought in wars. The PLA has not fought in a large-scale conflict since the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979 (and the ensuing border conflicts). As time has gone on, this has meant that fewer and fewer PLA officers have experience in conflict. It is notable, then, that the CMC has bucked this trend. Two of the current CMC members—Vice Chairman Zhang Youxia and General Li Zuocheng—have wartime experience, which is generally consistent with past CMC iterations. As these older members phase out, fewer CMC members will have experience in a war.

Previewing Changes to the CMC at the 20th Party Congress

Armed with these insights, it is possible to forecast some of the potential outcomes of the 20th Party Congress.

First, if the CCP leadership upholds norms around retirement for CMC members, four of the six military members are set to retire. Vice Chairman Xu Qiliang and Vice Chairman Zhang Youxia were both born in 1950, putting them well beyond the usual age for staying in office. Defense Minister Wei Fenghe and Chief of the Joint Staff Department Li Zuocheng are both 68, just past the typical requirement age.

If all four retire, precedent would suggest that the other two members, Admiral Miao Hua and General Zhang Shengmin, are well-positioned to become the next Vice Chairmen. Over the past 25 years, all CMC Vice Chairmen (except for one) previously served as a regular CMC member prior to being promoted to Vice Chairman. However, it is perhaps more likely that just one of the two is promoted to Vice Chairman since both hail from political (rather than operational) career tracks. It is possible that one of the other current members—particularly General Wei and General Li since they are just at the cutoff age for retirement—could break retirement age norms to become Vice Chairman. Alternately, a non-CMC member could be catapulted into the position. While the latter outcome would be untraditional, Xi has demonstrated a unique tendency to fast-track many top officers for promotion.

Regardless, it is highly likely that several new members join the CMC after the 20th Party Congress, and they will likely be current members of the 19th Central Committee who have reached the grade of theater command leader. Of the 29 CMC Vice Chairmen and members over the last 25 years, virtually all of them (except one) were on the Central Committee prior to promotion to the CMC. There are currently 16 un-retired members of the PLA on the 19th Central Committee at the theater command leader grade from which the future CMC could draw.5

One person who stands out as having a good chance of promotion to the CMC is General Liu Zhenli, who has been Commander of the Army since 2021. He is one of the few members of the Central Committee with experience in combat (in the China-Vietnam border conflicts of the 1980s), and he is only 58 years old, which means he could serve at least two terms on the CMC without breaking retirement age norms.

If the leadership disregards Central Committee membership as a prerequisite for promotion to the CMC, General Lin Xiangyang stands out as a potential candidate. He is the current Commander of the Eastern Theater Command, which played a starring role in the unprecedented August 2022 military exercises around Taiwan. Like General Liu, he is approximately 58 and could therefore have a longer tenure on the CMC.

Broadly speaking, Xi will likely want to ensure that the makeup of the CMC is at least as diverse as the current one. This could include appointing at least one Vice Chairman who is not from the Army and including at least one member each from the Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force. There will also likely be a premium on appointing officers with combat experience or extensive operational experience to ensure that the PLA is as battle-ready as possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment