Derek Williams and Adam Lowther

Why the Nuclear Triad Matters: With the United States actively aiding Ukraine in its war against Russia, while also aiding Taiwan in its effort to deter an invasion from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Americans are living in one of the most dangerous periods in history. No longer can Americans bask in the glow of the post-Cold War “Unipolar Moment.” Instead, the world is proving even more dangerous than during the bipolar period in which a democratic West faced off against the communist bloc. The new tri-polar period, although in its infancy, is starting out as unstable as many political scientists projected.

Admittedly, Russia is not an economic peer to the United States and the PRC is not yet a nuclear peer, but both states are attempting to use their nuclear arsenals to coerce the United States into abandoning democratically elected governments Kyiv and Taipei. Given the current international security environment, it is worth reflecting on the role deterrence and the nuclear triad play in ensuring strategic stability.

The Nuclear Triad and Deterrence

According to the Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military Terms, deterrence is defined as “The prevention of action by the existence of a credible threat of unacceptable counteraction and/or belief that the cost of action outweighs the perceived benefits.” Using all instruments of national power, the U.S. alters the adversary’s decision-making process, encouraging restraint. The most effective strategy tailors messages to an adversary’s culture, beliefs, and interests. Deterrence requires capability, credibility, and communication.

Deterrence by the threat of punishment is a concept that relies on the threat of imposing costs on an adversary to alter their decision calculus. This is accomplished by holding at risk what an adversary values. Targets can include industry, infrastructure, military forces, and the adversary’s population. It was the clear threat of nuclear war that ensured the Cold War remained cold.

Deterrence by denial occurs when the desired benefits of an adversary’s potential actions are reduced or eliminated by defensive measures. Denial can be achieved through passive defense, active defense, or offensive operations. The adversary must understand the risk to success posed by denial efforts, which means it is important to effectively communicate those efforts.

Deterrence by dissuasion is the least assertive form of deterrence and seeks to change an adversary’s perception of interests by convincing them that there are effective ways to achieve national interests without challenging the international status quo. These more passive approaches to deterrence can include the use of international norms to shape behavior and the use of carrots instead of sticks. The effort to bring Russia into NATO in the years immediately following the Soviet Union’s collapse is an example of deterrence by dissuasion.

What is important to remember about maintaining effective deterrence is that it takes capability (the ability to impose costs), credibility (the adversary’s belief you will do what you say), and the ability to effectively communicate with an adversary. Without all three, it is challenging to maintain stable deterrence.

Assurance is the art of convincing an ally that the United States will defend its vital interests in the face of a threat from a nuclear-armed adversary. If successful, the U.S. gains nonproliferation benefits by discouraging allies from developing independent nuclear capabilities. Assurance is more than just extending a rhetorical “nuclear umbrella” over allies. Denis Healey, a former British Secretary of State for Defence, once noted, “It only takes 5 percent credibility of American retaliation to deter an attack [from the Soviets], but it takes 95 percent credibility to reassure the allies.” Simply put, achieving assurance is harder than achieving deterrence.

Visible actions like maintaining a sufficient force posture and military exercises with allies reassure allies that the United States is reliable. These and related activities are the reason that no American ally has developed an independent nuclear weapons capability in more than sixty years.

Nuclear Triad

There are three legs of the nuclear triad that each possess unique attributes. Together, they produce a mutually supportive and flexible strategic deterrent for the country. These unique and overlapping capabilities allow the triad to become more than just the sum of its parts.

The triad’s overlapping attributes help ensure the enduring survivability of American deterrence capabilities. They allow the president to hold adversary targets at risk of attack throughout any crisis or conflict. Because each leg of the triad has distinct strengths and weaknesses, the president can hold a range of static, hardened, relocatable, hardened and deeply buried, time-sensitive, geographically complex, and area targets at risk. These target sets present a diverse set of challenges for American nuclear capabilities.

Bombers

Bombers are the most flexible and visible leg of the triad. Flexibility comes in two forms. First, they can attack an adversary from any direction, which makes them ideal for difficult targets. Bombers can strike any target regardless of terrain, borders, or location. This flexibility is only enhanced by the fact that the B-52H carries the variable-yield air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) and the B-2 can carry either the ALCM or the variable-yield B-61 gravity bomb. Thus, bombers are able to strike targets with a low-yield option and limit damage.

Second, bombers are the only leg of the triad that, once launched, are recallable. This attribute pairs with the visibility of bombers. Because bombers are “generated” in a way that is visible to space-based surveillance satellites, they provide the United States the ability to signal an adversary and escalate in discreet steps that then offer the opportunity to deescalate—the ultimate objective. Loading bombers with nuclear weapons, moving them to forward bases, and conducting flights in a geographic region are visible ways to signal an adversary of American resolve and intent. Only bombers have the ability to engage in such overt displays of power.

Image of B-2 Spirit stealth bomber. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

The ALCM and its eventual replacement, the Long-range Stand-off (LRSO) cruise missile, extend the effective range of bombers and deny sanctuary to the enemy. By extending the range of bombers, cruise missiles reduce risk to aircrew, increase aircraft survivability, and reduce support requirements for stand-off strikes, such as tankers and strike-support aircraft. Cruise missiles increase the survivability of each bomber since each cruise missile’s survivability is independent of other cruise missiles. The survivability provided by cruise missiles lends to the credibility of the bomber leg and the stability of nuclear deterrence.

Bombers are, however, vulnerable to conventional attack while on the ground. While in the air, the B-52H is vulnerable to advanced anti-aircraft systems, which is why the venerable aircraft only engages in stand-off attack with cruise missiles. It is this susceptibility to attack that makes the second leg of the triad so important.

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM)

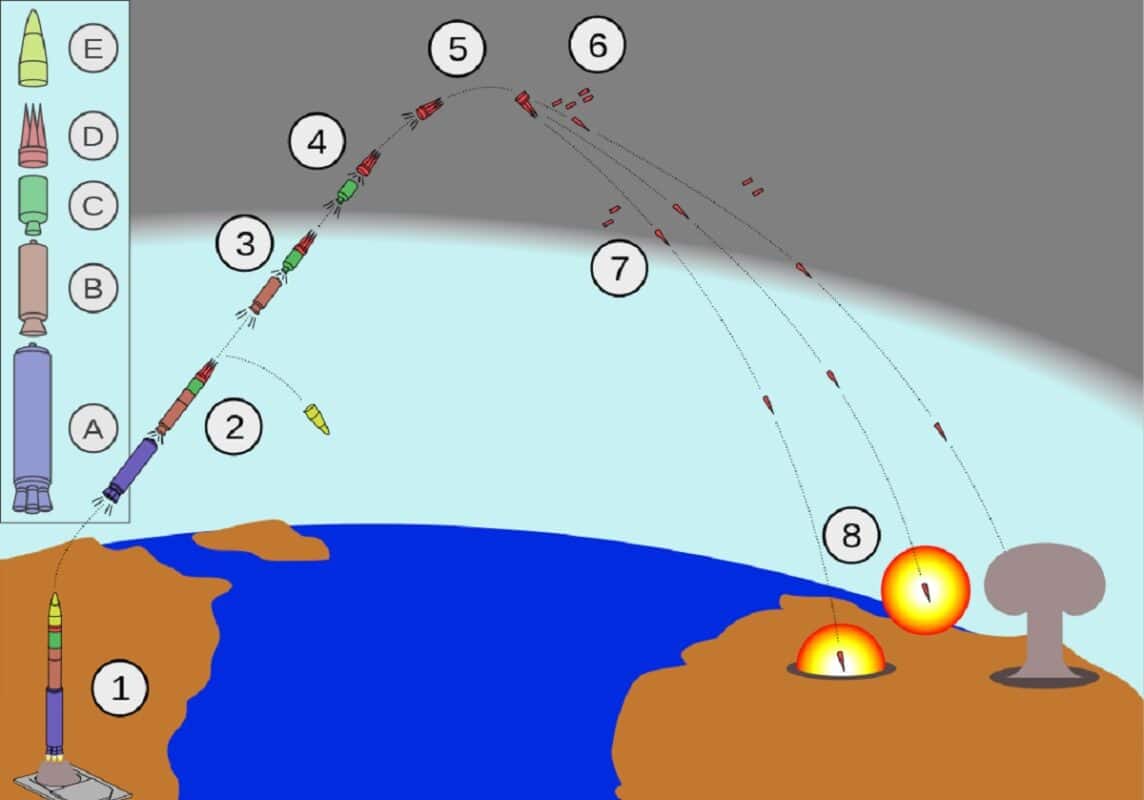

ICBMs are the nation’s “on alert” nuclear force that provides a 24/7/365 option that can strike targets 5,000-10,000 miles away in less than half an hour. Because the ICBM force is always on alert, the president can strike time-sensitive targets if necessary. Their ability to penetrate existing defenses provides an assured strike capability. With only a small number of submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM) on alert at any given time and with the bomber force off alert, the alert status of the ICBM is particularly vital.

In order to destroy the American ICBM force, an adversary must strike more than 450 hardened targets. This is a daunting task that demands an adversary maintain a large and accurate fleet of ICBMs. Even with such a capability, the risk of failing to destroy the entire ICBM force is significant and a reason for pause when contemplating an attack on the United States.

Diagram depicting the different stages of a Minuteman III missile path from launch to detonation, as well as the different basic stages of the missile themselves. Based on information in TRW Systems. (2001) Minuteman Weapon System History and Description.

This is an important point worth reiterating. Unlike the bomber and submarine force, destroying the ICBM force requires a large-scale nuclear attack on the American homeland. Thus, the stakes are much higher. Sinking a ballistic missile submarine with a torpedo or shooting down a bomber may not lead to a nuclear response, but a nuclear attack on the ICBM fields certainly would.

The weakness of the ICBM force is its stationary position. Both Russia and China know exactly where every American Launch Facility and Launch Control Center is located. While they are all hardened and buried, an accurate strike would destroy them. Thus, the sea leg of the triad provides the most survivable nuclear forces.

SLBM

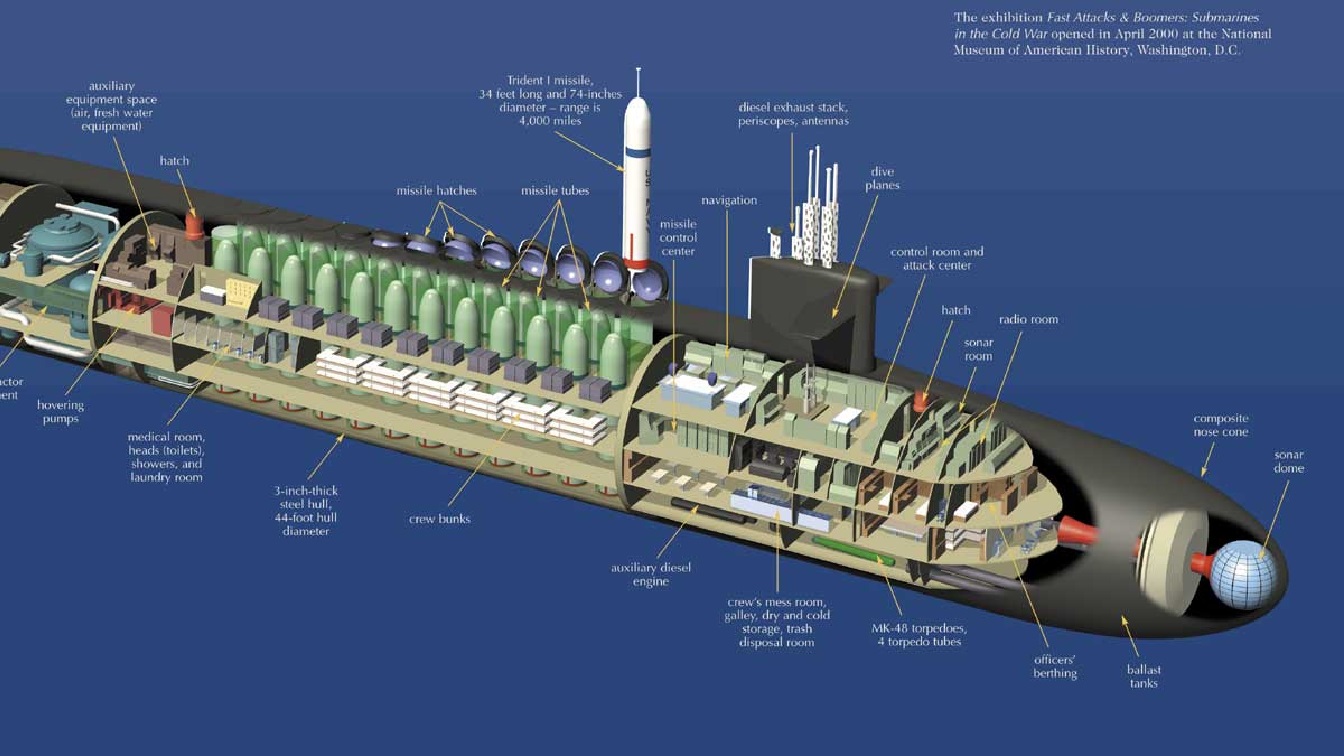

Submarine-launched ballistic missiles provide the most secure leg of the nuclear triad. Submarines combine mobility, accuracy, and high yield to hold hardened targets at risk. Unlike ICBMs submarines can move, which allows them to modify their launch point to minimize third-country overflight and change the angle of attack—striking challenging targets. Submarines also have a more diverse re-entry angle than ICBMs—making it harder to defend against them. While not prompt, like ICBMs, submarines provide an on-alert option to the president that is able to shape its trajectory and therefore alter warning time for the adversary.

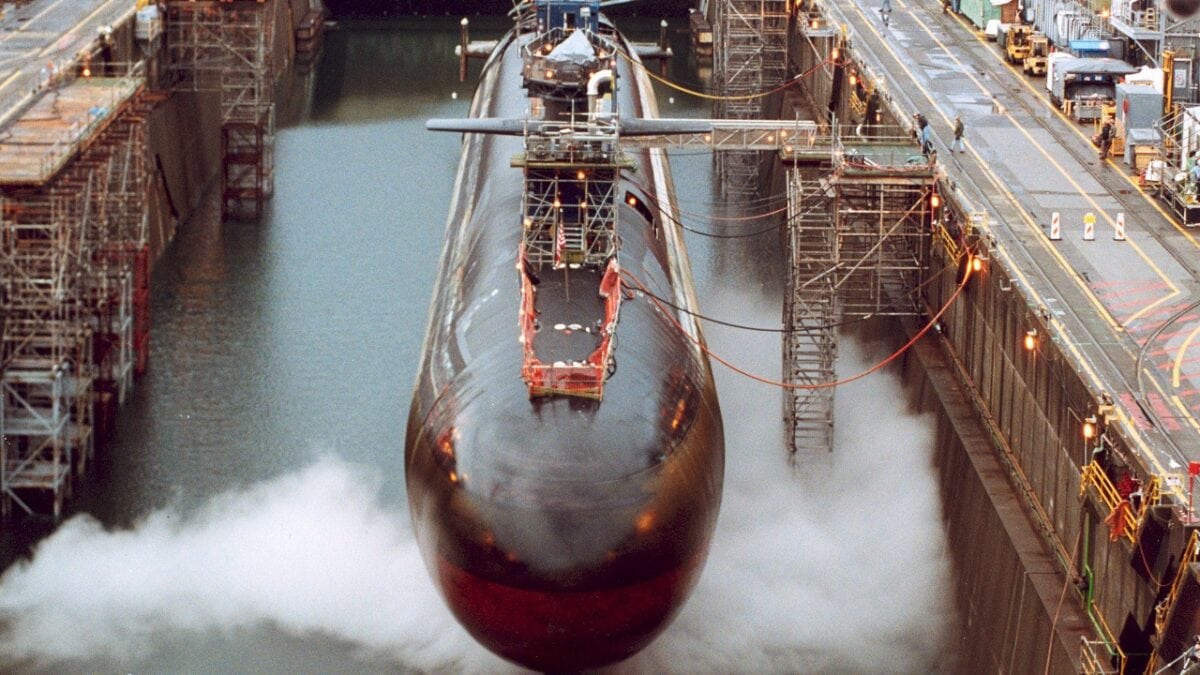

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Wash. (Aug. 14, 2003) — USS Ohio (SSGN 726) is in dry dock undergoing a conversion from a Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN) to a Guided Missile Submarine (SSGN) designation. Ohio has been out of service since Oct. 29, 2002 for conversion to SSGN at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Four Ohio-class strategic missile submarines, USS Ohio (SSBN 726), USS Michigan (SSBN 727) USS Florida (SSBN 728), and USS Georgia (SSBN 729) have been selected for transformation into a new platform, designated SSGN. The SSGNs will have the capability to support and launch up to 154 Tomahawk missiles, a significant increase in capacity compared to other platforms. The 22 missile tubes also will provide the capability to carry other payloads, such as unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and Special Forces equipment. This new platform will also have the capability to carry and support more than 66 Navy SEALs (Sea, Air and Land) and insert them clandestinely into potential conflict areas. U.S. Navy file photo. (RELEASED)

The great weakness of submarines lies in the potential of an adversary to engage in effective anti-submarine warfare. With the advent of small and stealthy unmanned underwater vehicles, it is becoming more likely that ballistic missile submarines will be tracked from port. High-performance computing and the eventual development of usable quantum computing will, at a point in the not-too-distant future, make the world’s oceans far less opaque to space-based intelligence capabilities.

Decision-making

Eliminating any leg of the triad would ease adversary attack planning and allow them to concentrate resources and attention on defeating the remaining leg(s). Thus, a triad of bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs not only provides the president with a range of options for striking adversary targets, but the triad makes an adversary’s decision to strike the United States difficult and dangerous. The United States employs a deterrence-by-denial strategy against nuclear-armed adversaries, presenting three unique problems for pre- and post-launch survivability. Let us explain further.

Under pre-launch conditions, an adversary must counter a large dispersed and hardened target set (ICBMs), a mobile undersea stealth-like target set (submarines), and a globally deployed target set (bombers). These capabilities require adversary investments into intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance in order to find, fix, track, and target dispersed bombers, deployed submarines, and counter-force capabilities to engage fixed and mobile forces. Counter-force capabilities require a large number of prompt, accurate, and high-yield weapons; anti-submarine warfare capabilities; and air/missile capabilities—to identify and strike bomber bases.

US President Joe Biden. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Although the bomber force is vulnerable when not on alert, bombers become survivable once generated to an alert status because of their ability to launch on limited warning and disperse to a larger number of bases. ICBMs also deny an adversary the ability to preemptively destroy the American arsenal with a small-scale strike requiring the destruction of no more than 20 targets. The size of the ICBM force requires an adversary to target a large number of their weapons against counterforce (ICBM) targets instead of counter-value (cities) targets. The large and dispersed nature of the ICBM force discourages the adversary from targeting more weapons against American population centers due to the enormous retaliatory capacity of surviving ICBMs.

Under post-launch and retaliatory-strike conditions, the adversary must counter ballistic missiles originating from both known (ICBM) and unknown (SLBM) locations, penetrating bombers (B-2) and cruise missiles (B-52H). This forces an adversary to invest in anti-ballistic missiles, air defenses, and counter-cruise missile technologies. An adversary must make these investments and take these actions in an environment where there is a great deal of uncertainty, and the risk of failure means the destruction of society.

Is it any wonder that nuclear deterrence has held for more than seven decades?

Signaling

The triad communicates resolve to adversaries and allies alike. Bombers can forward deploy, allowing the United States to conduct overflights and presence missions. Such action complicates the risk calculation for an adversary, and it signals to our allies an American commitment—linking American interests with those of its allies. The bomber force is stabilizing because of its visibility and longer flight times to targets. A bomber’s ability to launch and be recalled allows for more presidential decision time, allows the adversary to reconsider actions, demonstrates resolve, and increases risk for the adversary.

An artist rendering of the future U.S. Navy Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines. The 12 submarines of the Columbia-class will replace the Ohio-class submarines which are reaching their maximum extended service life. It is planned that the construction of USS Columbia (SSBN-826) will begin in in fiscal year 2021, with delivery in fiscal year 2028, and being on patrol in 2031.

While bombers are the best option for signaling, the other legs possess attributes that improve deterrence and assurance messaging. ICBMs are on constant alert, signaling American resolve and commitment. Their sustained posture is also a strong constraining force during a crisis.

Submarines can also signal allies and adversaries by increasing their alert rate, deploying additional submarines, and directing deployed vessels to conduct port calls at American or allied overseas ports. These measures demonstrate resolve and commitment. However, increased submarine deployments may increase adversary fear of a first strike, adding uncertainty.

Deterrence Failure

American nuclear forces must achieve military objectives if deterrence fails. This requires an ability to tailor strike options for reestablishing deterrence. In the event of deterrence failure, conducting counter-force strikes, coupled with active and passive defenses, can reduce American casualties. This is only possible because the triad offers the diverse set of capabilities—described above—needed to provide the president with a range of options for retaliation and the restoration of deterrence.

Hedging and the Nuclear Triad

The last role nuclear weapons play is in hedging against an uncertain future. The triad’s variety of deployment methods (air, sea, and land); the multitude of delivery profiles (ICBM, SLBM, gravity bomb, cruise missile); and diversity of designs (W78, W87, W76, W88, W80 warheads, and B61 gravity bomb) protect the nation.

Hedging is important because of the possibility of technical failure within one leg of the triad, adversary breakout from existing force levels, and adversary technological breakout. By hedging with a triad, instead of a dyad (bombers and submarines) or a monad (submarines), the nation can protect against the risks just mentioned and return to a larger number of nuclear weapons if needed. The fact that the nuclear force can also return to alert status also signals U.S. resolve to its adversary, increases the credibility of its nuclear force, and if deterrence fails, provides the president options to restore deterrence and achieve US strategic objectives. This hedge force is critical to our ability to adapt to changes over time.

Conclusion

The nuclear triad is the foundation of American national security. All too often it is forgotten that the nation’s nuclear deterrent has served as the foundation of American security for more than seven decades. They have allowed the United States to engage in conflict abroad without the intervention of adversaries. Even today, it is because of the nuclear triad that both Russia and China exercise restraint when contemplating a change to the international order.

The peace dividend gained from the end of the Cold War allowed the United States to neglect the regular nuclear modernization that kept the American arsenal ahead of the Soviet Union. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recent threats to use nuclear weapons and China’s rapid expansion of its nuclear arsenal are clear signs that the world has changed. As former Secretary of Defense James Mattis said during a February 7, 2018 press conference, “America can afford survival.” He added, “Maintaining an effective nuclear deterrent is much less expensive than fighting a war that we were unable to deter.”

No comments:

Post a Comment