DR NITHIYANANDAM YOGESWARAN

- China is strategically advancing urbanisation in Tibet to strengthen its control over the region.

- In recent times, several new urban areas have emerged, although the pace of urbanisation remains relatively slow and is not as rapid as that observed in other parts of China.

- The article focuses on Tibet's swift urban growth and examines a few driving factors like population and their wider effects.

- The geospatial data is used to assess the urban extent and visualise the complex terrain.

- China is strengthening its role in the region with enhanced military and economic ties, plus new air routes between Kathmandu and Lhasa, opening doors for tourism and collaboration.

Backstory

Over half the world’s population now resides in urban areas, a figure only expected to rise, with estimates suggesting an urban population of 68% by 2050. This phenomenon is most pronounced in Asia and Africa, where nearly 90% of the urban population growth is projected. The rate of urbanisation is a critical metric in assessing a nation's progress, encapsulating various aspects such as economic development (evidenced by increased activity and employment opportunities), infrastructural expansion (including new roads and enhanced public transport systems), social evolution (marked by improvements in education, healthcare, and life quality), demographic shifts (altering population density and household dynamics), global competitiveness (fostered through international trade and investments), and environmental advancements (highlighted by efficient resource use and innovations in energy).

Approximately 65.2% of Chinese lived in urban areas in 2022, though with significant regional disparities. The eastern coast of China exhibits the most advanced urban development, with over two-thirds of its population living in cities. In stark contrast, western and central China, including Tibet, show slower urban growth. Among Chinese regions, Tibet presents a unique urbanisation narrative. With its comparatively low level of urban development, Tibet offers a fascinating study in contrast to other areas of China.

Nestled between India and the large population centres of China, Tibet has immense strategic and cultural significance. Since China consolidated control over the region in the 1950s, Tibet has remained a focal point of global attention, particularly over the political and human rights of its inhabitants. Beyond Tibet’s geopolitics and rich cultural and religious heritage, the region’s environmental significance is underscored by the terms often used to describe it, such as the 'Roof of the World' and the 'Third Pole'. The Tibetan plateau, a source for major rivers such as the Indus, Mekong, Yangtze, and Yellow, supports billions across a swathe of the Asian continent. The region's distinct ecosystem and challenging geography add to its allure and complexity.

Delving into Tibet's urbanisation through the lens of urban geography and geospatial technology, set against the backdrop of historical, cultural, military, and environmental significance, is not just a regional endeavour but a globally pertinent one. The dynamics of Tibet’s urbanisation, the underlying causes, and the far-reaching implications offer a unique perspective, contributing significantly to the broader narrative of urban development and its possible impact on India.

Overview of China's Administrative Divisions and Regional Classification

To better understand Tibet, it is essential first to grasp China's administrative divisions and urban classifications.

Figure 1 illustrates the administrative boundaries and divisions of China—source: Map generated by author, raw data arcgis.com.

These administrative divisions are categorised into several levels:

- Provinces: China has 22 provinces, each with its local government. They are the highest level of administrative divisions in China.

- Municipalities: There are four municipalities — Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing. These large cities have the same status as provinces and are directly controlled by the central government.

- Autonomous Regions: These regions— Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Xinjiang, and Tibet — have a high concentration of ethnic minorities and enjoy some degree of legislative independence from the central government.

- Special Administrative Regions (SAR): Hong Kong and Macau, the two SARs, have been given a high degree of autonomy. Their legal systems are separate from mainland China.

Each of these administrative divisions has further subdivisions:

- Prefectures: Mostly found in autonomous regions, they serve as intermediate administrative divisions.

- Counties: This level encompasses counties, autonomous counties, and county-level cities, commonly under the jurisdiction of prefectures or municipalities.

- Districts: Administrative areas within municipalities and larger cities.

- Townships: Rural subdivisions of counties, including towns, townships, and ethnic townships.

China also classifies its cities based on urban population size. These are:

- Megacities: 1 to 2 million urban population.

- Large cities: 500,000 to 1 million urban population.

- Medium-sized cities: 200,000 to 500,000 urban population.

- Small-sized cities: Less than 200,000 urban population.

Additionally, China is conventionally divided into three regions:

- Eastern Region: Includes 12 provinces and encompasses cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.

- Central Region: It comprises nine provinces, including Shanxi, Henan, and Jiangxi.

- Western Region: Consists of 10 provinces, such as Xinjiang, Tibet, and Qinghai.

Figure 2 displays the cities and towns in Tibet, which are mostly distributed throughout the mountainous terrain on every piece of available land. In recent years, many urban pockets have emerged. Some are near the borders. The towns and cities have noticeable infrastructure. Source: Map generated by author, raw data arcgis.com.

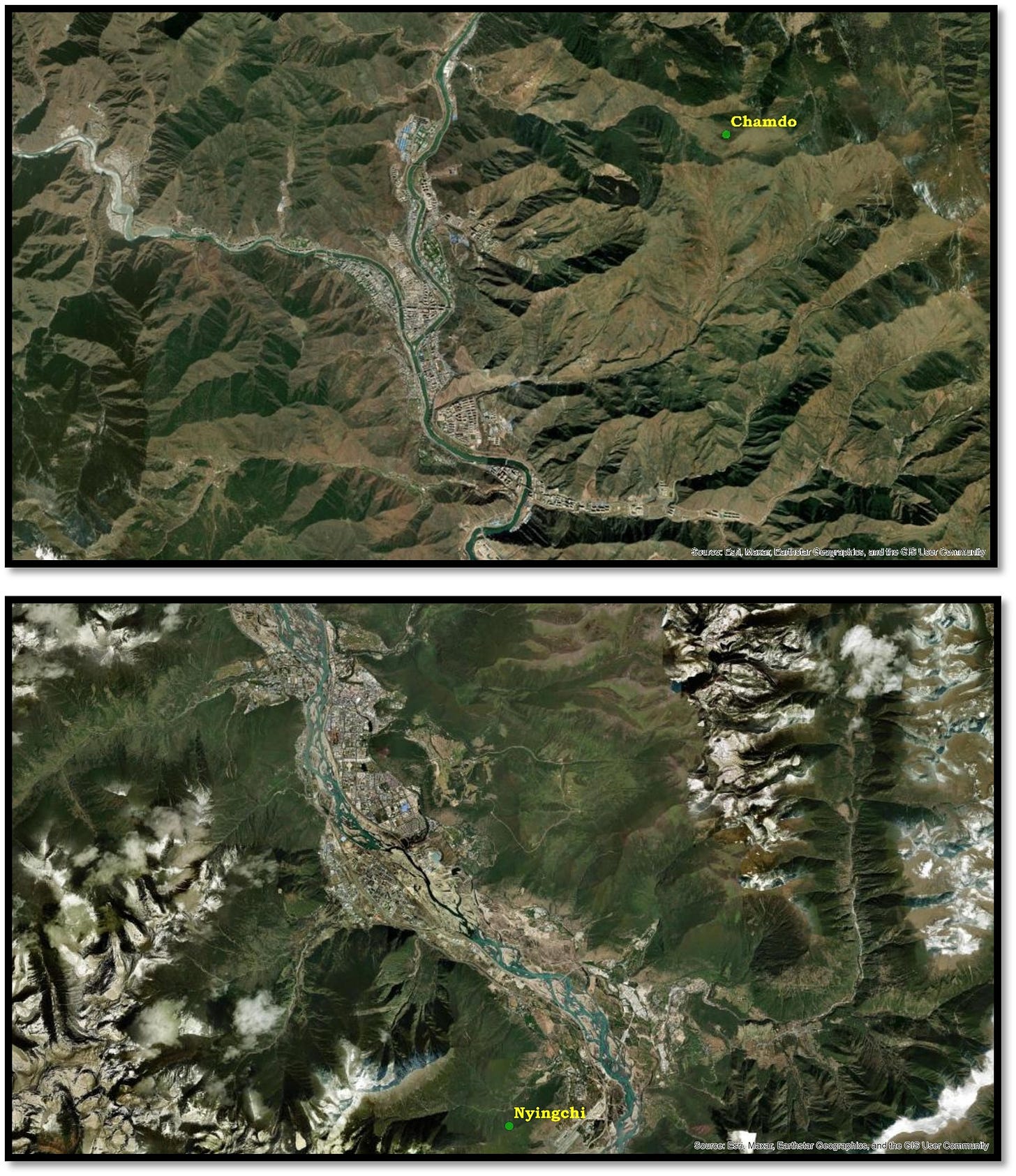

To give a comprehensive aerial perspective of the six major cities, the most recent satellite imagery has been utilised to demonstrate their urban extent.

Figure 3: The satellite image shows the extent of urbanisation in Lhasa and Xigaze cities located in Tibet. The images are self-explanatory, showing how these cities have expanded amidst rugged terrain. One common observation in both cities is their proximity to water bodies. Source: esri.com.

Figure 4 shows the urban extent of Nagchu and Gyangze. Cities in Tibet. These two cities are expanding rapidly in the last few years. Source: esri.com.

Figure 5 displays the terrain and spatial distribution of Chamdo and Nyingchi cities in Tibet. Both cities are situated on the banks of a river, surrounded by towering mountains. Source: esri.com.

Urbanisation trend in Tibet

The Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), situated on the Tibetan Plateau along the southeast edge of China, spans an area of 1.2 million square kilometres and has a population of 3.64 million, with Lhasa as its capital. This region, known for its rugged mountainous landscape and an average elevation exceeding 4,500 meters, is one of the least appealing areas in China for migration. Despite China’s efforts to promote urbanisation, Tibet's urbanisation rate remains below 37.39%, significantly lower than other regions in China. This is attributed to its harsh climate, craggy terrain, and limited economic prospects. However, China is undertaking various initiatives, including sustainable urban development projects in Tibet. By 2025, it's expected that the Tibetan Plateau, encompassing both Tibet and Xinjiang provinces, will host 16 million residents, with over half reaching moderate urbanisation stability.

Figure 6, the human footprint map, provides valuable insights into the population distribution across Tibet's vast and diverse landscape. The map reveals that the human population is mainly concentrated in the middle and eastern parts of Tibet, where there are major cities and townships that serve as centres for economic and cultural activities. The urban areas in these regions have a relatively high population density, indicating a significant human presence. In contrast, the western part of Tibet, characterised by rugged terrain and harsh climatic conditions, remains uninhabited mainly in many areas. Despite the environmental challenges, some communities have managed to thrive in these remote regions, relying on traditional lifestyles and practices to sustain themselves. —Source: Map generated by the author using arcgis.com.

It is interesting to note that since the 1970s, the rate of urbanisation in Tibet has undergone significant changes. Between 1970 and 1979, there was noticeable growth in both the economy and population. The population increased from 1.48 million to 1.83 million, with an annual growth rate of 2.14%. This was the region’s fastest population growth rate during that time.

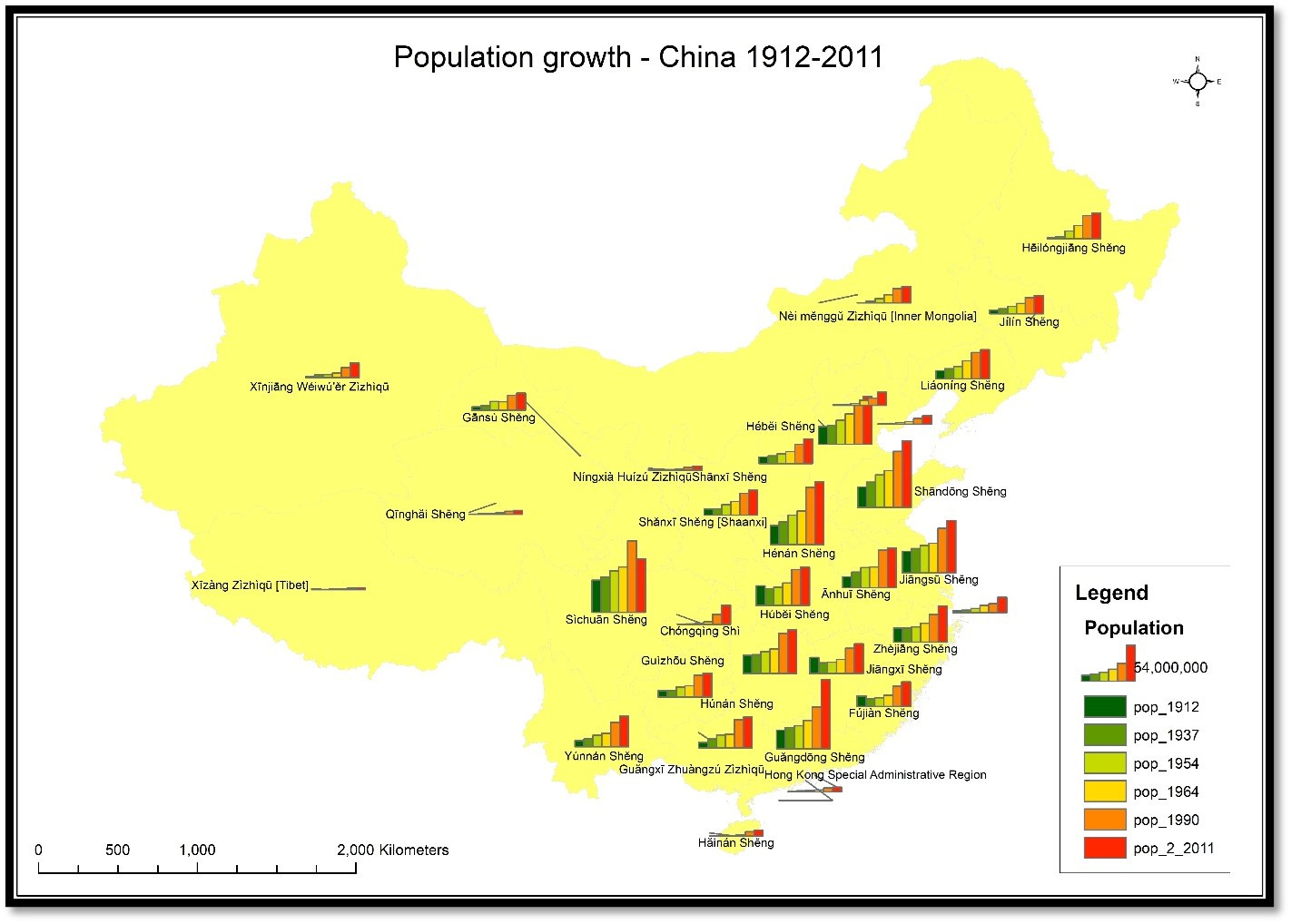

Figure 7 The figure describes the population growth rate in various provinces of China from 1912 to 2011. The bar chart shows a steady rise in population numbers over the years. It is worth noting that Tibet, also known as Xizang, had the lowest population count throughout the period—source: Map generated by the author, Source: Map developed by the author using arcgis.com.

Before 1951, Lhasa was the only semi-urbanised settlement in Tibet, with a population of over 10,000 and a total urban area of less than 10 square kilometres. In the 1950s, the region’s urban population was less than 70,000. However, after the government's efforts in urban development, including road construction, housing, and infrastructure, Tibet saw rapid urbanisation post-1951, indicating a 198 per cent increase till 2022. This was further boosted by China’s reform and opening-up policy in 1978. In recent years, there has been an increase in the speed of urban construction in Tibet, especially after the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012. In the 21st century, the urbanisation rate of Tibet reached 31.5% in 2019, a significant increase from its low base. As of the end of 2020, Tibet had six prefecture-level cities, 146 urban towns, and a total urban built-up area of 326 square kilometres.

Figure 8 shows the visualisation of urban centres in Tibet, as seen through night-time light data from earth observation satellites, revealing significant urban infrastructure. The intensity of the light, depicted in grey, indicates robust urban development in certain areas of the region. Brighter grey patches represent areas with higher urban light emissions, while lower light emissions are observed over water bodies, vegetation, and open land.

In terms of migration, TAR’s population has been increasing, with most of this growth attributed to the Tibetan people. As of 2010, Tibetans constituted over 90% of the region’s population. In contrast, the Han comprised about 8.17% of the population, with other ethnic groups accounting for 1.35%. The increase in the number of Tibetan people and the relatively small proportion of migrants in the region has been integral to China's social and economic development plans. Many engineers and technicians from other provinces in Tibet have contributed significantly to the region’s overall socioeconomic development. This migration has been essential in supporting urbanisation in the area.

The land cover map and DEM of Lhasa provide an overview of the complexity of the terrain.

Figure 9 depicts two images that showcase two distinct aspects of Lhasa City, the capital of Tibet. The first image illustrates the city’s different land cover types, while the second one presents a three-dimensional view of the city's land features. The images highlight the complexity of land usage in the city, where settlements are developed in deep valleys, wherever less rugged terrains are available. Source: map prepared by author and source data European space agency.

Urbanisation Drivers in Tibet

Urbanisation in Tibet encompasses traditional elements of urban growth. These include economic activity, government-led development and investment, demographic shifts, enhanced living standards and urban facilities. However, in Tibet's context, this urbanisation extends beyond these classic drivers. It encompasses broader goals such as land acquisition, resource extraction, and a strategic shift in the identity of local communities.

The region's relatively flat lands amidst its mountainous topography have been steadily urbanised, with support infrastructure being developed. This urban expansion often involves the appropriation of rural land for building infrastructure, residences, and commercial spaces, leading to the displacement of rural populations and a transformation of the traditional Tibetan lifestyle. The demand for urban land in China, including Tibet, is primarily met by converting rural land, resulting in considerable changes in land use and ownership patterns.

Urban pockets are established with substantial infrastructure to enhance the quality of life. These urban areas have essential amenities and key infrastructure like roads and airports. Urbanising Tibet plays a pivotal role in large-scale initiatives. A key focus of these endeavours is contributing to China’s ambition to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. To this end, renewable energy sources such as hydroelectric and solar power are being harnessed from the inhabitant regions, and supporting mechanisms are established in nearby towns and villages. These energy sources not only benefit the Tibetan regions but also have the potential to help other regions in the country.

Moreover, rivers flowing through Tibet can provide essential freshwater resources to other parts of China, especially those facing water scarcity. China's large-scale damming of rivers on the Tibetan plateau to generate hydropower affects the water supply to a vast population in Asia. Tibet's rich mineral resources, including copper, lithium, gold, and silver, are being mined on a massive scale, contrasting with traditional Tibetan practices that avoid disturbing the land. This has resulted in the transformation of Tibet's landscapes, the displacement of Tibetan nomads, and the degradation of local ecosystems.

Thus, the distribution of populations across various geographical regions can be beneficial for multiple reasons, including resource allocation and development in remote locations, as well as other strategic advantages.

Possible concerns to India due to urbanisation in Tibet

The issue of urbanisation in Tibet has been a significant concern for India, primarily due to strategic and geopolitical factors. It is often believed that any potential war between India and China would occur along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). China's territorial claims on Arunachal Pradesh and other areas have heightened tensions. Additionally, India's support for the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile has been a longstanding issue that has caused friction between India and China. China’s recent change to use “Xizang” instead of “Tibet” in its official diplomatic communications and geographical data sets is seen as a strategic effort to alter historical perceptions. Another significant concern for India is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which involves infrastructure development in Tibet. These developments could enhance China's regional strategic presence, raising security concerns for India.

Parting shot

As we closely monitor the recent developments near India's border, particularly the increasing Chinese presence in Bhutanese territory and the growing alliance between China, Bhutan, and Nepal, the geopolitical landscape in the region appears to be in flux. The recent visit of Bhutan’s foreign minister to China has raised the potential for diplomatic shifts that might impact India’s strategic interests. Furthermore, China's military and economic influence in the region and the expansion of air connectivity from Kathmandu to Lhasa indicates possible tourism and cooperative developments. In the context of rapid urbanisation in Tibet, our future coverage aims to comprehensively analyse the various factors that have contributed to this phenomenon. Using geospatial data, we will delve deeper into the impact of urbanisation on the region's economy, environment, and social fabric. Overall, our analysis seeks to offer a nuanced understanding of the complex dynamics of urbanisation in Tibet and shed light on how this process shapes the region's future.

No comments:

Post a Comment