Kai He

This year is likely to be remembered as a turning point in history because it could signify the emergence of an Asian Nato – a multilateral security alliance in the Asia-Pacific led by the United States and consisting of its traditional bilateral allies in the region such as Australia, Japan, South Korea and the Philippines. This grouping will target China, the elephant in the room.

The idea of an Asian equivalent to the transatlantic security alliance was previously considered a far-fetched notion for two reasons. First, the US-led “hub-and-spokes” system, consisting of a series of US bilateral alliances, had been successful in maintaining regional security in the Asia-Pacific. In other words, an Asian Nato was not considered necessary.

Second, while the role of the US as the “hub” was not questioned, the relationships between the “spokes” have been strained for decades. For instance, historical issues have plagued the ties between South Korea and Japan, and Japan had a bitter experience with Australia during World War II.

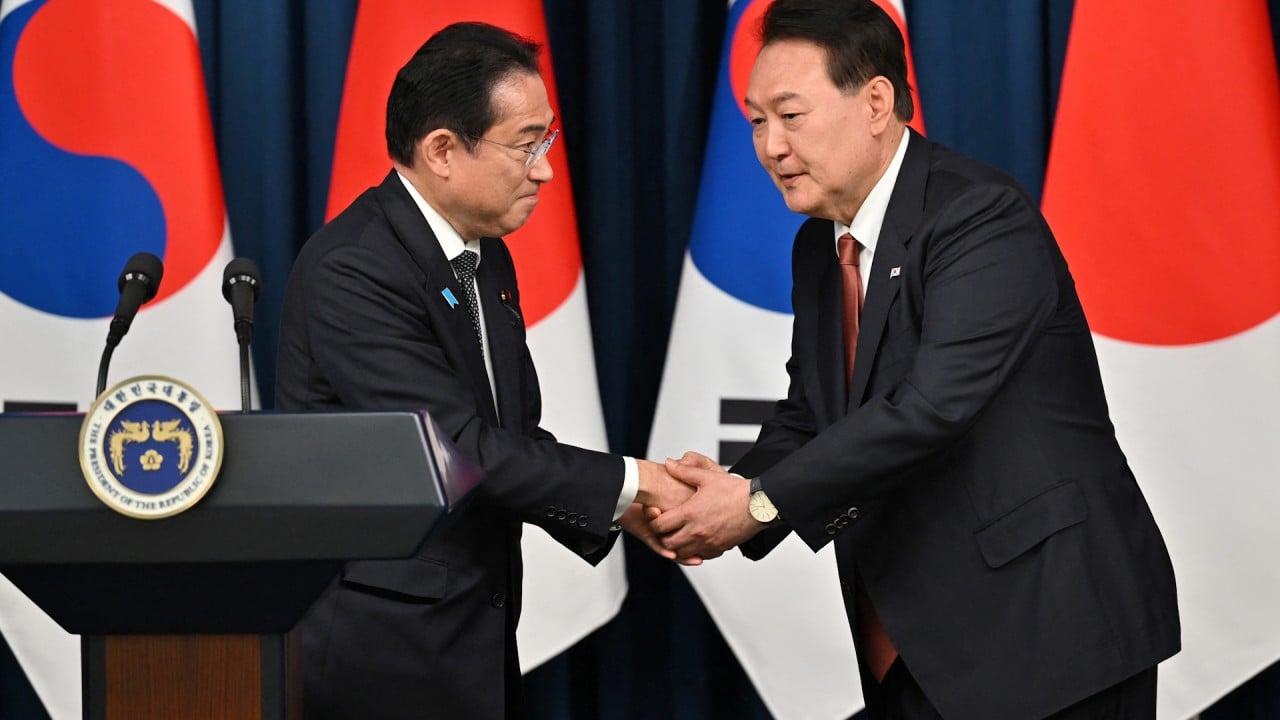

The geopolitical landscape has experienced significant shifts recently. Last October, Japan and Australia strengthened their security partnership by signing a new security agreement. In March, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida met in Tokyo to put an end to the two nations’ trade disputes and start the process of rapprochement.

The most consequential development, however, has been the intensification of US-China strategic competition since the spy balloon incident in February. President Xi Jinping has accused the US of trying to contain, encircle and suppress China. Furthermore, the meeting between Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, and US House Speaker Kevin McCarthy in Los Angeles has further strained the already-contentious bilateral relationship. As a result, China has suspended high-level meetings with the US.

Leaders of South Korea and Japan commit to stronger ties despite lingering historical disputes

Leaders of South Korea and Japan commit to stronger ties despite lingering historical disputes

On the other hand, the US has arranged a series of leadership summits to reinforce its bilateral alliances this year. In January, US President Joe Biden welcomed Kishida to the White House, reaffirming America’s commitment to Japan’s defence. In March, Biden met Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in San Diego to discuss the Aukus defence agreement.

April brought a high-profile visit by Yoon to Washington, during which the US announced it would deploy nuclear-armed submarines to South Korea to deter North Korea. Finally, earlier this month, Biden met Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr, pledging to support the Philippines in its South China Sea disputes against China.

During Biden’s meetings with leaders from Australia, Japan and the Philippines, a common message was to strengthen security and defence cooperation and counterbalance China’s growing influence in the Asia-Pacific. However, the challenge lies in how to reinforce the “hub-and-spokes” system. One logical way could be to upgrade the system to that of a multilateral military alliance – an Asian Nato in which the US and its Asian allies make a mutual defence pledge of “all for one and one for all”.

This Asian Nato might also attract US security partners in the region such as Singapore and India, which could further complicate China’s position. While India is a non-aligned country, it has been a core member of the Quad security grouping, a “soft balancing” mechanism against China in regional security. Soft balancing could be seen as a preparatory step toward future “hard balancing”, such as forming a military alliance.

US touts ‘ironclad’ commitment to the Philippines amid rising tensions in South China Sea

The idea of an Asian Nato might not be seen as unnecessary and undesirable, as it was in the past. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in which Nato’s collective efforts in supporting Ukraine and sanctioning Russia have proved successful, US leaders might begin to reconsider the utility of a multilateral defence arrangement in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly as tensions rise over Taiwan.

While some Asian leaders might still pay lip service to the idea that they do not want to choose between the US and China, an Asian Nato could be seen as a useful tool to collectively counter China’s potential challenges.

However, the establishment of such an alliance would inevitably lead to the beginning of a new cold war, not only in Asia but globally. This is because it could prompt China to form military alliances with Russia and other like-minded countries, leading to the world being divided once again into opposing blocs.

To discourage the formation of an Asian Nato, China must prioritise diplomatic efforts to address its neighbouring countries’ threat perceptions. Adopting a “wolf warrior” diplomacy approach will be counterproductive. Chinese leaders should instead engage in dialogue and seek to resolve disputes peacefully. Signing a code of conduct in the South China Sea with Southeast Asian nations could be the first diplomatic step.

Additionally, resuming high-level talks with the US is crucial as cutting off communication is in neither party’s interest. Although strategic competition between the two nations is inevitable, they have yet to fully determine how they will compete with each other. The creation of an Asian Nato implies a competition driven by conflict.

Beijing has the option to shift this competition to being less confrontational by leveraging alternative security architectures such as Asean-led multilateralism. Finally, China could consider revamping the non-aligned movement with India and Indonesia to resist the potential Asian Nato and a new cold war.

Kai He is a professor of international relations and director of the Centre for Governance and Public Policy at Griffith University, Australia. He is also a non-resident senior fellow at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) (2022-2023). The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in the article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USIP

No comments:

Post a Comment